Toying with ideas of magic, the occult and spiritualism, Emily Hunt contends with the way that portraiture can both memorialise and re-animate a subject. Based in Berlin, Hunt is an Australian contemporary artist who works across sculpture, painting, installation, ceramics, printmaking and performance. She first learnt printmaking in the early 2000s at the Sydney College of the Arts with the Australian artist Mike Parr, and has pinpointed this introduction into the alchemical process of printmaking as ‘my entry point into magic and esotericism’.

Hunt orients her practice in dialogue with art history and everyday image making, cultivating excess and opulence in her heavy layering of form and embellishment. Sometimes straying into the realm of the grotesque, she pulls together visual threads that bind Renaissance masters such as Albrecht Dürer and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, frescoes, grottoes, satirical illustrations and folklore.

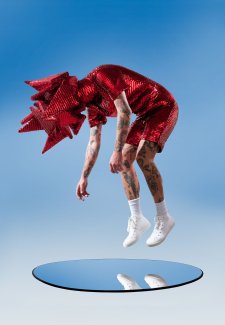

This distinct visual language culminated in her 2023–24 series Homunculus trance, which was presented as part of her Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition The Grotto in 2024. The six ornately detailed handmade marionettes in the series incorporate sculpture, ceramics, costume, woodwork, silk painting and printing on fabric. Each puppet is modelled on a person from Australian cultural history who is associated with spiritualism and the occult, including art critic James Smith (1820–1910), artist Rosaleen Norton (1917–1979) and violinist Leila Waddell (1880–1932). Hunt hand-modelled the heads of each marionette in ceramic, richly ornamented with brightly coloured glazes and gold luster detailing. The effect is uncanny; the faces are rough-hewn and, at their smaller than human scale, are distinctly unsettling.

The title of the series references the homunculus – a miniature human brought to life – a concept popularised in 16th-century alchemy. This idea was embodied in the marionettes that were puppeteered by the artist in performances as part of the exhibition, during which Hunt staged conversations with each subject as if enacted through a séance.

‘My etchings, murals and ceramics tap into the imaginal realm which is the bridge between the material and spiritual realms,’ Hunt said of the exhibition. ‘There is connection between ornament and magic, decoration and the divine, that I find most compelling. Practising magic is an artform in itself and I believe that making art is also a form of magic.’

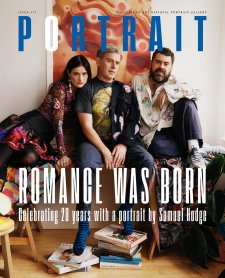

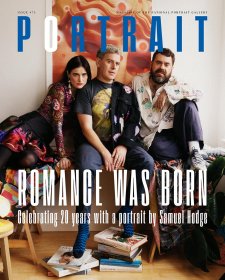

1 (James Smith) Homunculus trance 2023–24 from Homunculus trance 2023–24. National Portrait Gallery Purchased 2024 © Emily Hunt. Photo: Jessica Mauer. 2 (James Smith / Joshua Smith) Chain of being, 2023-2024. Both Emily Hunt.

In the marionette (James Smith) Homunculus trance, recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery along with etchings of Smith, Rosaleen Norton and Leila Waddell, the figure of the influential art critic is reimagined and recontextualised through the spiritualist beliefs that dominated the latter part of his life. A journalist, art critic, intellectual and public speaker, Smith was an ardent supporter of the visual arts and believed in its ability to elevate the cultural and intellectual life of Australia, his advocacy extending primarily to art that fell within his deeply conservative standards. This stands in stark contrast to his later interest in spiritualism in the 1870s, and his controversial beliefs that education could be enabled via magnetic transmissions from dead scholars and artists. Painted on the marionette’s cheeks are two pencils, signposting Smith’s work as art critic and writer. The text ‘Amuanuesis’, written in gold down the ridge of his nose, refers to the mediaeval scribe Amanuenses who was known to translate the experiences of visionaries into written form.

Each Homunculus trance marionette was made to be paired with an etching from Hunt’s Chain of being series. The paired etching for (James Smith) Homunculus trance, (James Smith / Joshua Smith) Chain of being (2023), is both a portrait of a person (or two people) and a portrait of place. The artist has depicted James Smith as the central character in the scene which references his journalism in publications such as The Argus and The Harbinger of Light. Here, Hunt overlays Smith’s status as art critic with the visual allusion to William Dobell’s Joshua Smith: evoking the story of the portrait that won the Archibald Prize in 1943 and the resulting legal case that split the artistic community and destroyed a longstanding friendship between Dobell and his subject Joshua Smith. Hunt speaks of this etching as an exploration of ‘the theme of hope and disappointment associated with esoteric beliefs or creative dreams’. She positions Smith as a symbol of contradiction and paradox, reflective of the tension between his ardent conservatism and his radical obsession with spiritualism. This tension finds apt material form in the etching, a medium that itself embodies the idea of the paradox: a print is produced as a reversed reflection of the plate. A ghostly trace that is slightly askew – much like the occult itself.

1 (Rosaleen Norton) Chain of being, 2023-2024 Emily Hunt. 2 Performance still of Emily Hunt: The Grotto presented at the Art Gallery of NSW on 26 June 2024 Photo © Art Gallery of NSW, Anna Kucera and Jenni Carter.

Many of Hunt’s etchings, including (Rosaleen Norton) Chain of being (2024), draw on early cartography where the physical experience of a journey, full of narrative, mythology and symbolism, is depicted in two-dimensional form. Sydney-based artist and occultist Rosaleen Norton first garnered media attention when she exhibited a series of spiritualist drawings at the Rowden White Library at the University of Melbourne in 1949. Police raided the exhibition to confiscate works and place obscenity charges on Norton, which were later dismissed in court. Much of the sensational mythology around Norton was fuelled by the Australian media who dubbed her as ‘the witch of King’s Cross’ in the 1950s and 1960s. In Hunt’s etching, the artist alludes to her subject’s occult spiritualism, positioning her in front of an altar-like structure emblazoned with the word ‘weplon’ – the name of a monstrous creature conjured from Norton’s imagination that often appeared in her artworks. Norton’s face is adorned with symbols that represent her ideas about art, connectivity and the afterlife, with the text ‘Qliphoth’ referencing the manifestation of evil or impure spiritual forces in Jewish mysticism.

Hunt’s artworks disrupt and subvert historical representations of spiritualist figures by re-casting them in a contemporary frame. She similarly explores physical spaces – such as the city of Sydney – and generates her own internal maps of magical places which are later articulated in visual narratives. The places depicted are dually physical landmarks experienced by Hunt in her life and psychological reference points to her own thoughts or beliefs. In the Chain of being series Hunt reproduces various locations around Sydney that she describes as ‘psychically charged’ as a way to ‘banish banality’ and ‘re-enchant’ the city. For example, the foreground of (Rosaleen Norton) Chain of being includes both the Darlinghurst Goal and the Kirkbride complex at Callan Park where Norton’s long-time friend, collaborator and lover Gavin Greenlees was interned and later passed away. In later years, both locations would become the site of art schools.

1 (Leila Waddell) Chain of being, 2023-2024 Emily Hunt. 2 Installation view of Emily Hunt: The Grotto at the Art Gallery of NSW, 22 June – 7 October 2024 Photo © Art Gallery of NSW, Felicity Jenkins and Jessica Mauer.

Location is also central to (Leila Waddell) Chain of being (2024), although this time the work bridges the famous musician and philosopher of magic’s international status with her deep connection to Australia. Born in Bathurst, Leila Waddell moved to Sydney as a child to study violin under Henri Staell. She later taught at several prestigious girls’ schools before achieving great success playing with symphony orchestras across the United Kingdom as well as in France, Germany and Russia. In London she developed a relationship with the English poet, writer and occultist Aleister Crowley and began studying magic as part of Crowley’s order the AA (Astrum Argentum). She became the high priestess of this new mystical religion, which merged Theravada Buddhism and ceremonial magic. Crowley wrote a series of seven public invocations called the Rites of Eleusis, dedicated to the seven planets of antiquity, and Waddell played a key role in the performance of the rites at Claxton Hall, London in 1910. In the upper-right corner of the etching, Hunt has depicted Waddell playing her violin, wearing the ritual robes from the Rites of Eleusis, while at the centre of the composition, she performs the ritual. Linking back to Australia, a waratah flower and cicada beetle sit alongside reproductions of iconic Sydney statues such as Il Porcellino and Matthew Flinders’ cat ‘Trim,’ which are located out the front of 19th-century sandstone buildings on Macquarie Street.

These recent acquisitions not only bring three influential Australian cultural figures into the collection, they bring them to life. Introducing ideas of sentient puppetry, the séance and channelling the dead into portraiture, Hunt offers a mischievous way to consider how a portrait survives its subject. ![]()

Keep an eye on the National Portrait Gallery’s socials to find out when Emily Hunt’s works will be on show.