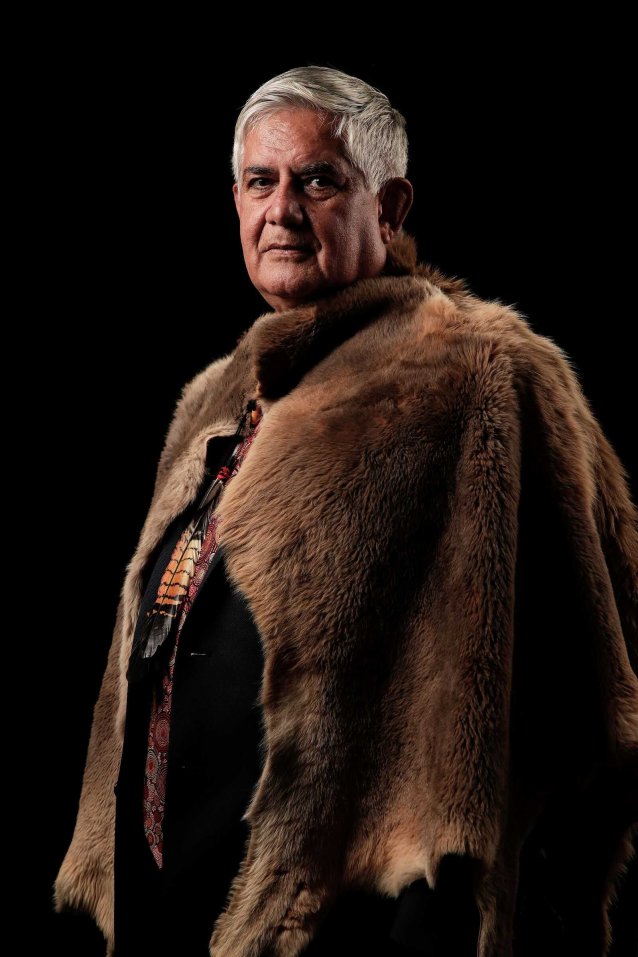

Each year a prominent Australian speaker is invited by the National Portrait Gallery to deliver a lecture that explores the intersection of portraiture and identity. In this edited extract from the 2025 Andrew Sayers Memorial Lecture, writer and columnist Jacqueline Maley lifts the curtain on how political portraiture is used as a tool to change hearts and minds, acknowledging that the formidable power it wields can be a double-edged sword.

olitical portraits capture defining political moments and reframe national conversations. But what, if anything, do they reveal about these people we see so much of in the daily news? How do these images connect with, and even influence, the reputation and identity of the politicians who lead us?

Now, I show you this portrait with profuse apologies to former Opposition Leader Peter Dutton because it is on the public record that his media minders really, really didn’t like this picture. It was taken in 2016 in Parliament House, by the renowned press gallery photojournalist Alex Ellinghausen. Alex works for the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age, and he is one of the best in the business.

The photo was taken on budget day, when most of the journalists in the press gallery are in the hostage situation which is known as the budget lock-up. But Dutton, who was then immigration minister, wasn’t in the lock-up. He called a press conference in what’s known as the Blue Room of Parliament House.

Alex Ellinghausen also wasn’t in the lock-up. And as a consequence, his workload was a little lighter that day. He had a little more time and freedom to experiment. He positioned himself below Dutton, who was at the podium speaking, and when he pressed the shutter button, the light projected upwards, the podium cropped the light, and the result was the mask-like effect we see.

When Alex went back to the bureau office, he showed the photo to his colleague Andrew Meares, a multi-award-winning photographer who was with the Herald for nearly three decades. Mearsey, as we call him, told me that when they reviewed the picture, they knew it would be controversial and unflattering, but asked themselves, ‘On what grounds would we censor it?’

They couldn’t answer that question, so, in the interests of objectivity, they decided to file it to the editors. They decided that if they censored it, that would be a political act in itself.

Stephanie Peatling, a senior editor still with the Herald, tweeted the picture with the caption ‘Eek’, and Dutton’s media team saw it, and rang to ask her to remove it. After some negotiation, she agreed, but on the proviso that she post a statement about why she was removing it.

But as we know, despite its ephemeral nature, social media does not forget. It was a classic own goal. Dutton’s office had tried to shut the image down, but they ended up publicising it more widely. So why did Dutton’s office care so much about one bad picture? Because they knew its potential power.

A politician can do many things in their career, but one or two images of them may end up summing them up for voters in a way that they don’t like. Or that they think is unfair. Untruthful, even. That is the power of a portrait.

That is why politicians want so badly to control their images – because they know that when the image is out there, published, in the political ether, it is not their property anymore. It doesn’t belong to them. It belongs to us, the voters. It becomes ours.

The combination of digital photography, smartphones and the internet has led to an explosion of images. Those images can be distributed globally in a near-instant process we call ‘going viral’. We live in an age where the manipulation of images is commonplace, and increasingly hard to spot. No wonder politicians want to assert some control, some sovereignty, over their own images.

It has become commonplace for prime ministers and opposition leaders to have their own official photographers while, every day, politicians’ offices send out alerts for what are known as ‘picfacs’, which are stage-managed picture opportunities meant to document the rather visually boring business of government.