When early studio photographers across Africa began photographing weddings, christenings and families in their communities, there was an emphasis on showcasing the fact that Africans too could be extravagant and polished. This came after decades of photographs depicting simple traditional lifestyles, fetishised golden artifacts or exaggerated stereotypes that appeased the intended Western audiences.

In my early photographic work, namely The Studio Series in 2015, I sought to honour the legacy of the early studio photographers like Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta and Samuel Fosso. These men (and almost all the early photographers were men) saw the camera for what it was; a tool which had been weaponised against Africans but could be used for and by us.

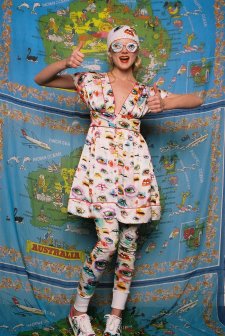

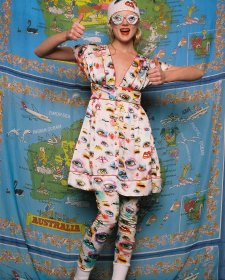

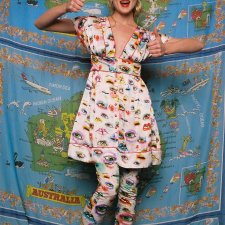

When I began making Men In This Town (MITT), I chose to photograph myself rather than my family members or people in my community like I had done for The Studio Series. MITT was created in early 2024 not long after I had begun to recover from the birth of my first child. I felt drawn to investigate the public ownership of my postnatal body and the roles requested of it when it was contextualised either beside my child or on its own.

MITT is as much about surveillance as it is about performance. We learn to move or dress our bodies depending on how we feel about the parts of us that are digested by the public. This also applies to our face, size, gender, race, social roles etc. My body, from the moment it was publicly seen as one carrying a child, took an interesting journey into public ownership and then into subtle rejection. The act of carrying a baby holds such deep cultural significance that it often overshadows the person who has sacrificed parts of their body to bring the child into the world.

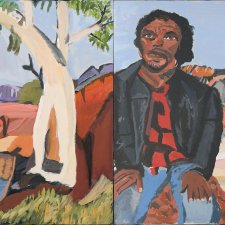

MITT combines feminist theory with the history of African studio photography and the colonial relationship to the body. Through suiting, set dressing and posing, I chose to make self portraits that are not fictional but rather performative. There is an important distinction between the two as I believe performance is an extension of our reality, a necessity and a tool, while fiction is the imaginative and the sublime that can help us realise our performances.

The series invites the viewer to reflect on their own acts or responses to surveillance, just as it explores the history and biases of both the sitter and photographer. It is a conversation of gender, race, history and the very idea of an audience.

MITT is a small protest. It is also inspired by the history of drag and the parallels which appear in studio photography – particularly the dialogue between the sitter and their garments as expressions of cultural and gendered performance. My work was an opportunity for me to digest the relationship I have and have had to my body, as well as how my self-perception is informed by the public performances I have been covertly encouraged into.