Thom Roberts is fascinated by photocopiers. Machines of image-making, they do more than replicate and reproduce. For Roberts they are a means of creative production: his copies can be the origin of a painting or an installation, but they are also works of art in themselves. Roberts is a prolific photocopier – so much so that Studio A, the supported studio from which he works, gently limits his access to the office machine. Copies upon copies of people, trains and animals that are painted over, drawn on, or taped up. Repetition as an agent of creation, generating a spool of images that echo and recur but also distort and change with each run through the machine.

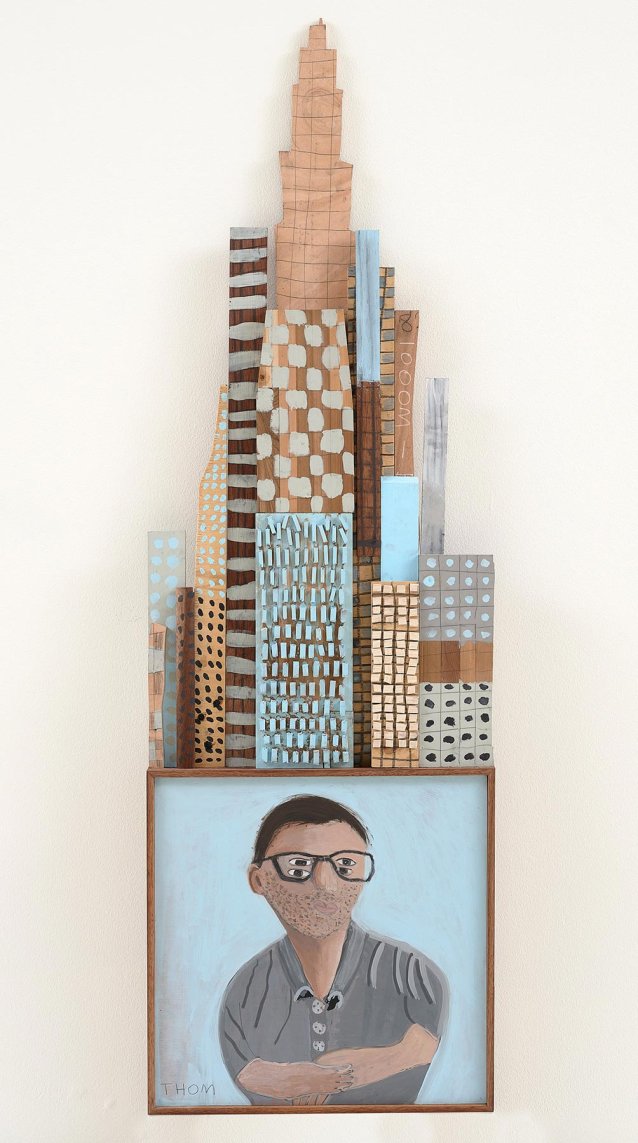

For Roberts, people also reproduce themselves. On meeting him, he may offer you a new name. He may also offer a type of train, or building, through which you can be identified. Roberts himself identifies as the CountryLink Express train and, now, the Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (having identified as the Burj Khalifa tower in Dubai for many years). When I met Thom, he asked if he could call me Neenish Cake.

For Roberts, people and infrastructure, trains and buildings are intertwined and overlapping entities. The limits between their edges are slippery; one thing can morph into the other. Much like an image that has been fed through the photocopier more than once.

By announcing, and documenting, these slippages in identity, Roberts expands the possibilities of portraiture. It is often presumed that the aim of a portrait is to faithfully reproduce a person’s likeness and respond to the material facts of the world. For Roberts, portraiture is not just a creatively malleable medium; it defines the world as he experiences it.

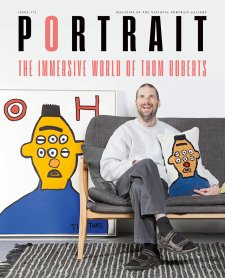

Roberts’ distinctive style, manifest across his painting, animation, installation and performance work, features idiosyncratic motifs: extra sets of eyes and noses or what he calls ‘piano teeth’. In these duplicated features we perhaps witness another instance of the ‘copy’ impulse at work. These faces clone themselves, a copy of a copy. They could equally be read as an homage to the glitch, the flourish of a rogue copy machine, or the accidental movement of paper mid-scan.

A Thom Roberts work is instantly recognisable, yet an attempt to describe and distil his practice merely in terms of the kinds of faces he crafts feels reductive, for this is a practice that blooms in abundance; not simply in the abundance of facial features, but in the vibrancy of colour, the declarative and bold linework, and the dizzying volume of production. Roberts is prolific; he gives the photocopier a run for its money.

The phrase I continually come back to when thinking about Roberts’ work is generosity. Generosity runs close to the eruptive energy of his artmaking, but it also allows us to articulate what his work does as a sustained act of world building. Roberts offers a way to see the world in all its multiplicity. As if it were being fed through the photocopier, glitches and all, until the ink spills into something else entirely.

This article was developed in collaboration with Studio A, a social enterprise that supports professional artists with intellectual disability. Thom Roberts’ solo exhibition is on show at the National Portrait Gallery from 12 April to 20 July 2025.

Thom Roberts shares the stories behind some of his portraits.

‘This is a portriff [portrait] of Diesel Plummer [artist Katy Plummer]. I love Diesel, she used to work with Skye Fox [Studio A artist Skye Saxon], back at the old building before we moved. I painted this for an exhibition. It was outside the Giant’s Castle [Carriageworks]. They were humongous. They looked good at the Giant’s Castle. I did her portriff a few years ago. Trains on that side, faces on the other side. I see people as trains and faces and also sometimes buildings. Diesel is a steam train. Me, I am the Kingdom Tower. I used to be the Burj Khalifa but I swapped buildings and now I am the Kingdom Tower. The tallest tower on this here earth.’

‘This is Big Bamm-Bamm. His real name is Ken Done, but I call him Big Bamm-Bamm after Bamm-Bamm Rubble in The Flintstones. I like to rename people and places, and I love The Flintstones. Big Bamm-Bamm is an artist like me and sometimes he paints the Harbour Fridge [Bridge]. I met him at Pink Panther Gallery [Mosman Art Gallery] when I had an exhibition there. He also visited Studio A and bought my cow sculpture. He told me, “I love your artwork.” I used the money to buy coffees! I sketched him when he came to Studio A, first in lead pencil and then in acrylic paint. I made it a big portrait, and I painted him with cat’s ears. People ask me, “Why did you paint him with cat ears?” And I say, “Because I do it Thom’s way.”’