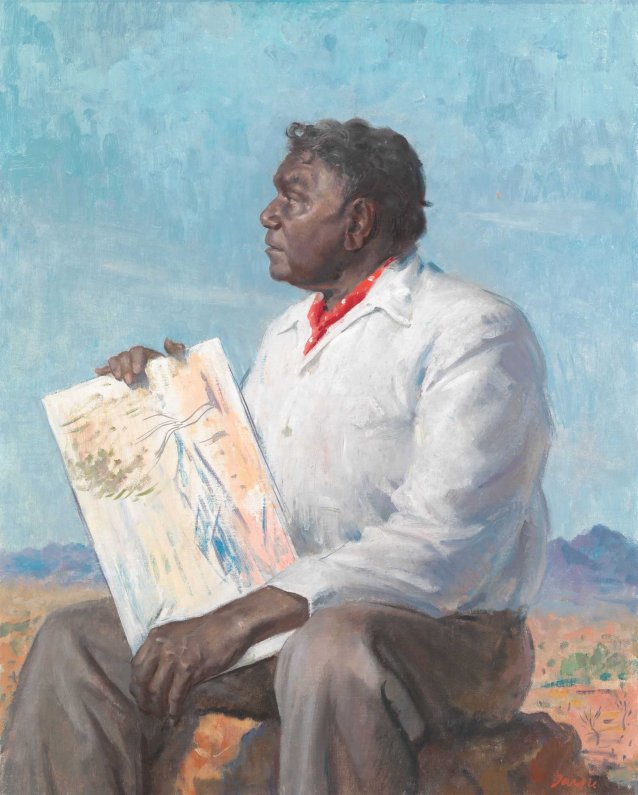

Another artist’s hand offers a decorative flourish held aloft. In his 1922 self portrait, George Lambert stands beside a cut-crystal vase arranged with glorious plumes of gladioli, wearing a dandyish corduroy cuffed smoking jacket. It was painted in Sydney following Lambert’s return from London, in the year he was elected an associate of the Royal Academy. A letter Lambert wrote to his wife Amy in November 1921 reveals the artist playing up to the perceived image of him as foppish aesthete: ‘I am a luxury, a hot house rarity … Scoffed at for preciousness. Despised for resembling a chippendale chair in a country where timber is cheap.’ And yet, Lambert was a working artist, and his hands, strong and indelicate, are those of a craftsman. In a 1922 Sydney Mail article, the author noted Lambert would rather be told by a critic that he had ‘“done his job well”, as one might address a bricklayer’. I am thinking of the lovely Ramsay portrait of Patterson again, and the way a hand is so revealing of the subject.

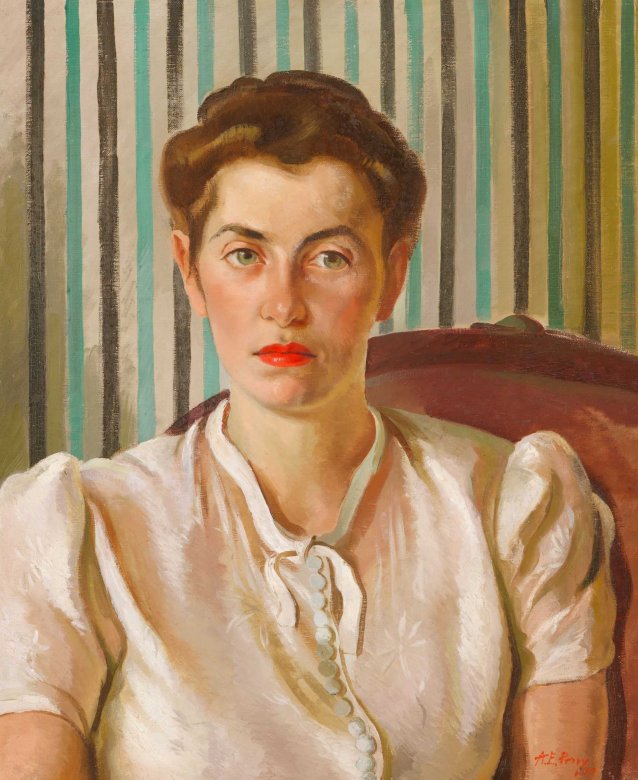

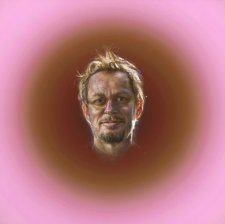

I add these portraits to the list of 48 paintings that will fill the walls of the gallery. Spanning the 1850s to the present day, they celebrate the achievements of activists, doctors and company directors, musicians, writers, a former Governor-General and a Queen. While we often find the subject of a painted portrait positioned in the centre of the composition – set in isolation, our attention focused on the individual – in this crowd of faces, solitary moments are brought together. Through a furtive glance, a held stare, a gesture extended or repeated, the sitters connect with us and each other across time and space.![]()