All photographs are portraits of the past. Shutters click and whoosh, a moment is ripped from the slipstream of what Susan Sontag, in On photography (1971), called ‘time’s relentless melt’. The medium’s elegiac bias is, for Roland Barthes, symptomatic of the ‘terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead’ (Camera lucida, 1980).

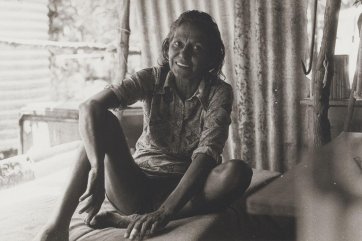

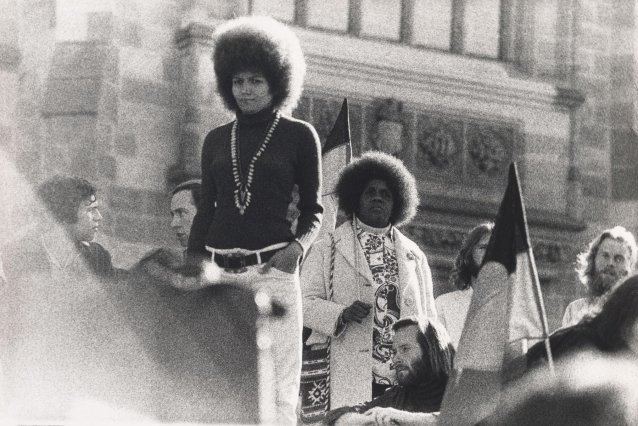

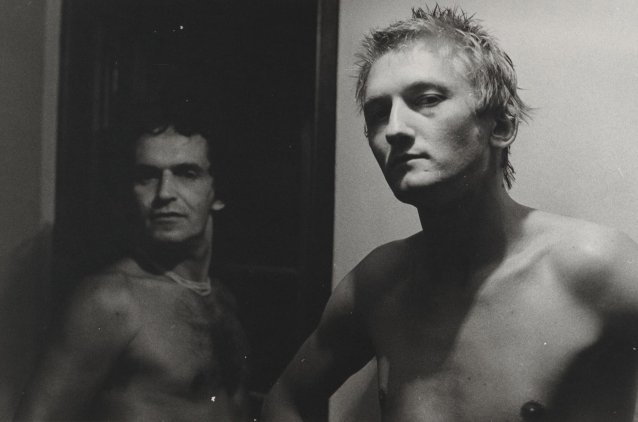

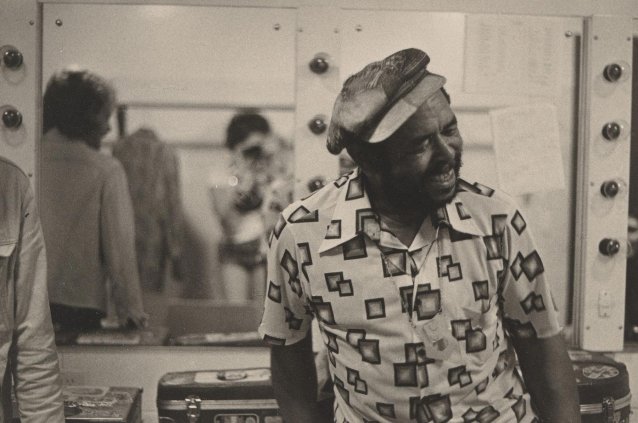

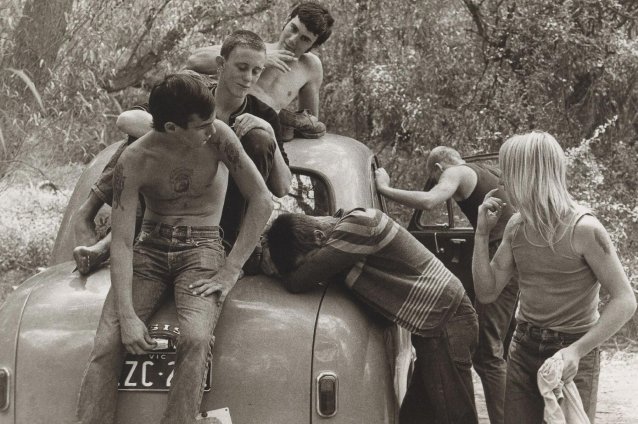

These melancholy words haunt me when I look at Carol Jerrems’ photographs, haunted in turn by the spectre of her premature passing, in 1980, at 30 years old. This body of work is not only a memento mori for a precocious talent, but also a requiem for the era Jerrems has come to personify. Today her mythos is inextricable from the countercultural milieu she chronicled with an inspired and uncommon affinity.

By the end of the 1960s, American writer Joan Didion had already declared the sun was setting on the Age of Aquarius: ‘All that seemed clear,’ she wrote in Slouching towards Bethlehem in 1967, ‘was that at some point we had aborted ourselves and butchered the job.’ Jerrems’ intimate portraiture confirms that time moved slower in the Antipodes, however; her images are populated by an idealistic generation enacting their nascent politics via trials in communal living, free love, creative cross-pollination and radical resistance. The photographer’s cultural moment is closer to that of Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip (1977), with its rotating cast of artists and dropouts falling in and out of one another’s beds, sharehouses and scenes. One of the anonymous interviewees in A book about Australian women (1974) – a collaboration between Jerrems and writer Virginia Fraser – summed it up neatly as ‘our period of great experimentation’.