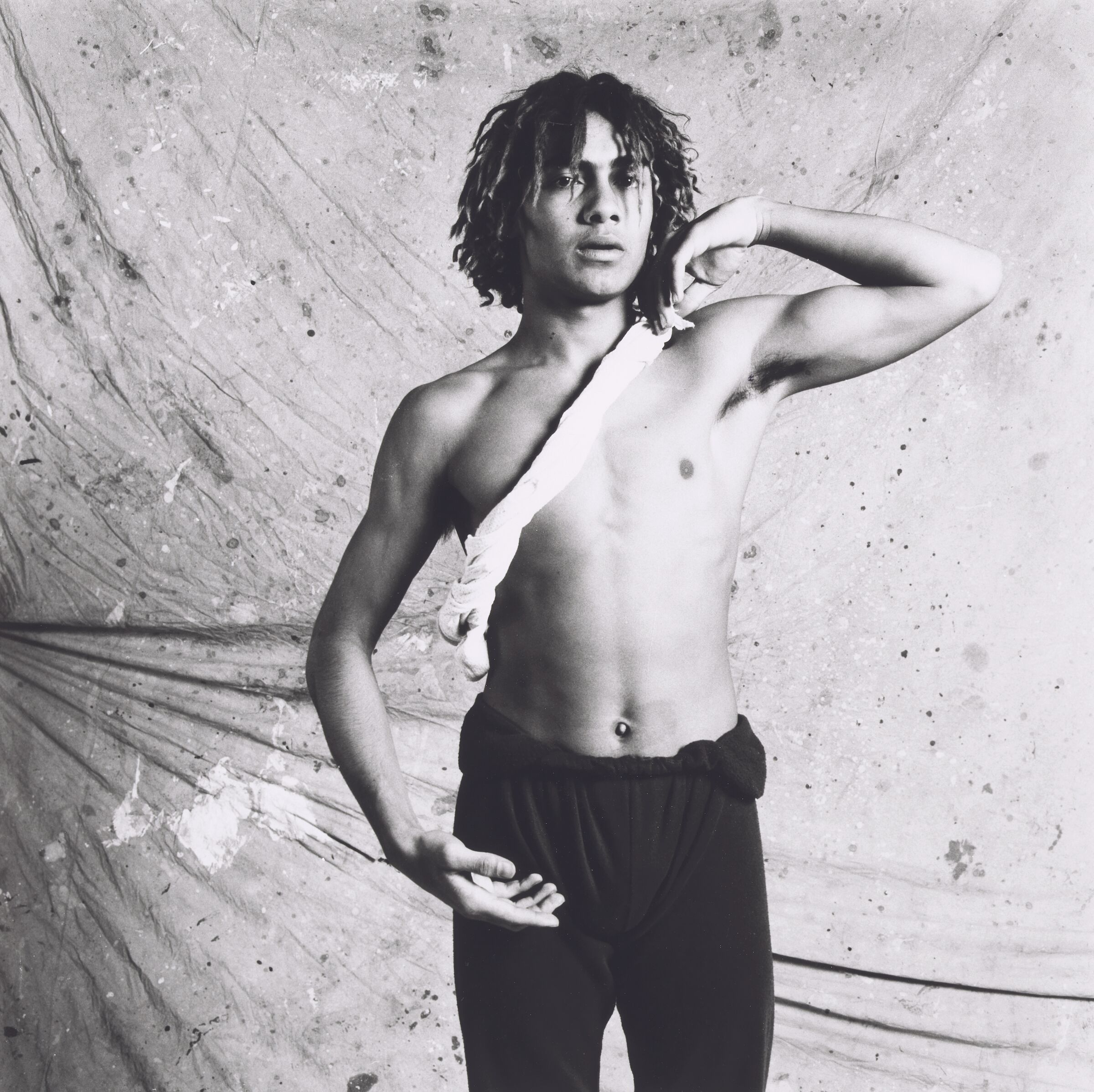

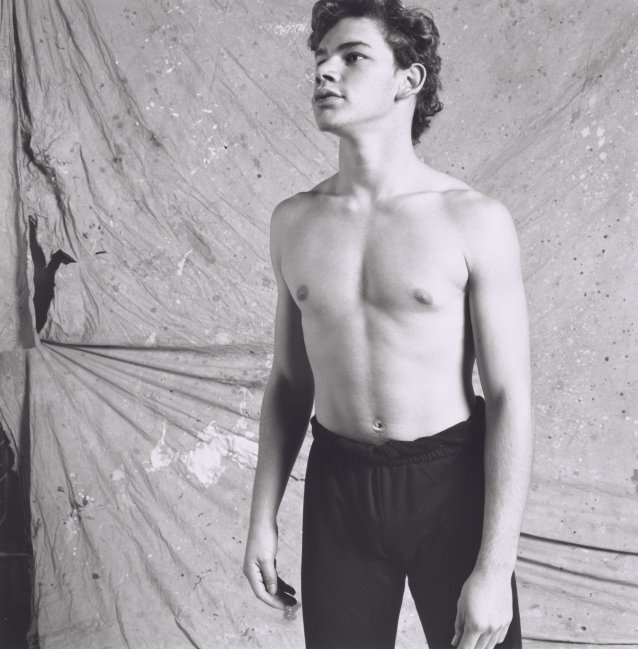

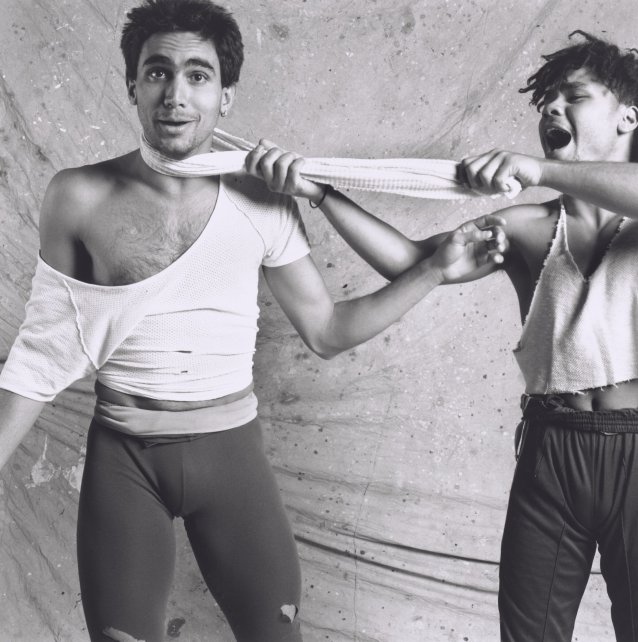

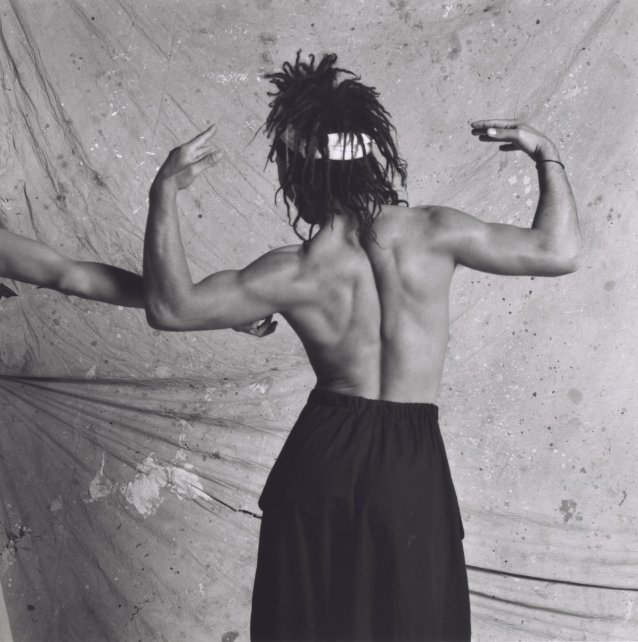

There is something abbreviated about Tracey Moffatt’s 1986 series Some lads. This is not one of Moffatt’s epic truncated unmade films, which is how most of her latter-day photographic series might be regarded. With her viewfinder, Moffatt constructs entire fictive worlds that exist in parallel with ours. They are lush evocations of the unseen, hallucinations that pierce some wound in the collective unconscious or glitching confabulations where time warps, breaking with history and public memory. Such is her skilful conjuring of these dreamscapes that you can dwell in them, be haunted by their banal violence or their ineluctable truth. You might even feel a perverse nostalgia for their characters or palettes or mise-en-scene, as I do. As with her most recent body of work, The Burning (2024), some of these dystopic worlds are traumascapes, as writer Maria Tumarkin has labelled sites of mass human suffering. In our ontologies, this belief is expressed in the Aboriginal English term ‘poison country’, where extreme violence or collective suffering scars the Country itself so that it becomes toxic. But by 1986, Moffatt had not yet led us through the wormhole – the dimension where she conjures her wild, disjointed yet utterly plausible existential narratives that spellbind audiences and critics alike.

In the artist’s exhibition history, Some lads is widely recognised as her first major public body of work – after The Movie Star (1985), her iconic portrait of the late David Dalatnghu Gulpilil AM, painted up, holding a can of Fosters while stretched over the bonnet of a car on Bondi Beach, and before her experimental film Nice Coloured Girls (1987). Some lads predates the series which consolidated her position as one of Australia’s most gifted and visionary artists, the suggestively titled Something More (1989), by three years. A mildly erotic kink-out set in the canefields of the tropical north, the iconic suite of images is populated by tropes – from the leering canecutter sweating it out in his slab hut playing knife games, a sexually available woman greeting the viewer at her open door in a silk negligee, foiled by Moffatt herself in a lurid red cheongsam with asymmetrical hem. She is both the expectant Madonna – and the unmade film’s protagonist – waiting for a sign. As she awaits deliverance, the tragic heroine is jeered by a gang of whitebread Vegemite kids and soothed by a Gauguinesque character crosspollinated with Bacchus, the hedonistic god of wine. The anti-trope breaking all the rules in this small town, Moffatt’s conjuring and the series’ alternate reality, is a female motorcycle cop – in high-shine boots, brandishing a whip.