While Ben was being followed by the whole world and participating in an interview with CNN, the painter of Michelle Obama’s portrait, Amy Sherald, came across a similar picture of Parker. Sherald posted the photo on Instagram with the statement, ‘Feeling all the feels’, with a crying-face emoji. Recounting her first visit to a museum when she first saw a strong and positive depiction of a man who could have been her father, Amy identified closely with the toddler; ‘I knew I wanted to be an artist already,’ she recalled, ‘but seeing that painting made me realise that I could. What dreams may come?’ Within two days, Amy’s post received over 31,000 likes, including one from Michelle Obama herself, who later met with Parker at her office. Footage of the two of them having a dance party also went viral.

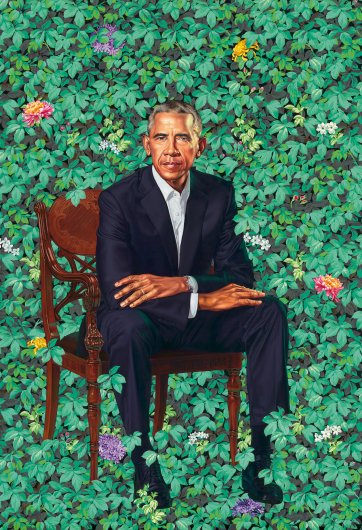

Such has been the ‘Obama Effect’ since the portraits were unveiled on 12 February 2018, at the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. At present (March 2018), an estimated 4,000 articles have been written about the portraits; 1.25 billion people have reached out via social media; and in the first month since the unveiling, the museum has more than doubled its normal attendance. While it is nice to think – as Ellie, our social media maven suggests – that for a short moment the National Portrait Gallery in Washington ‘broke the internet’, the more satisfying aftermath has been the dawning realisation to many outside the art world that portraits have power, and the stories we tell in our galleries can indeed change the world.

To some extent, the Obama Effect has brought the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery full circle since its opening in 1968, 50 years ago. In that year of tumult, Americans were grappling with issues of identity. The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy were killed; the country was at war in Vietnam; and disaffected citizens were marching in the streets to the rally cry of ‘Power to the People’. Today, America is once again seeing the rising of grassroots activism. Black Lives Matter, sanctuary cities, the Women’s March, the #metoo movement, protests against gun violence led by high school students, and Stand up for Scientists are all contributing to a moment of internal conversation.