Film stills photography is a complex and fascinating sub-genre of photographic portraiture. Starstruck: Australian Movie Portraits – the National Portrait Gallery and National Film and Sound Archive’s collaborative exhibition – explores the way stills photographers operate in a dualistic setting, inhabiting both the functional reality of the film set and the fictional world being created for audiences. It sees them creating both portraits of actors and portraits of actors’ characters – as well as those intriguing, illustrative moments ‘in between’ – with the resulting images defined in correspondingly diverse ways: as movie publicity shots, as documentary photography, as fine art.

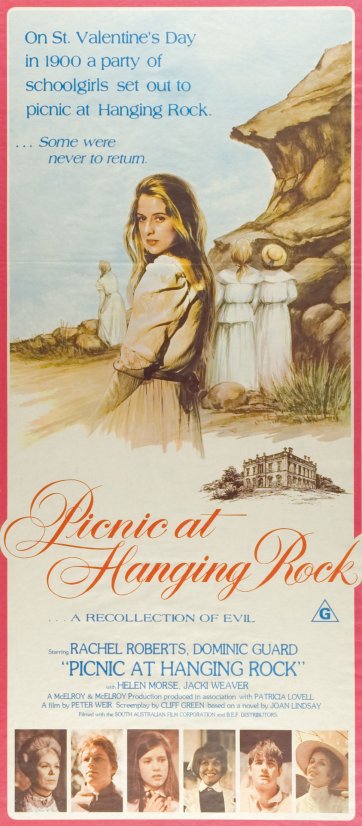

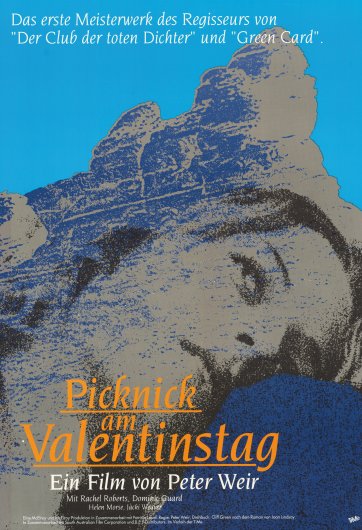

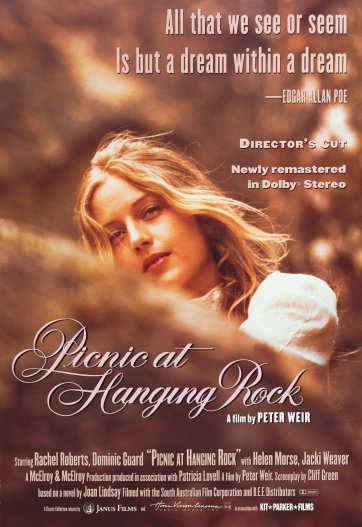

The stills from director Peter Weir’s iconic Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) embody this melding of fantasy and reality; it’s hard to tell where actor Anne-Louise Lambert ends and her character Miranda begins. Picnic, based on Joan Lindsay’s novel, is one of Australia’s most famous 1970s new wave films. It hovers delicately between lush costume drama and horror, and its publicity campaign focuses on Miranda, one of the schoolgirls who vanished at that fateful picnic on Valentine’s Day 1900. As described by one reviewer: ‘she was the beautiful girl who leads her classmates into oblivion’.