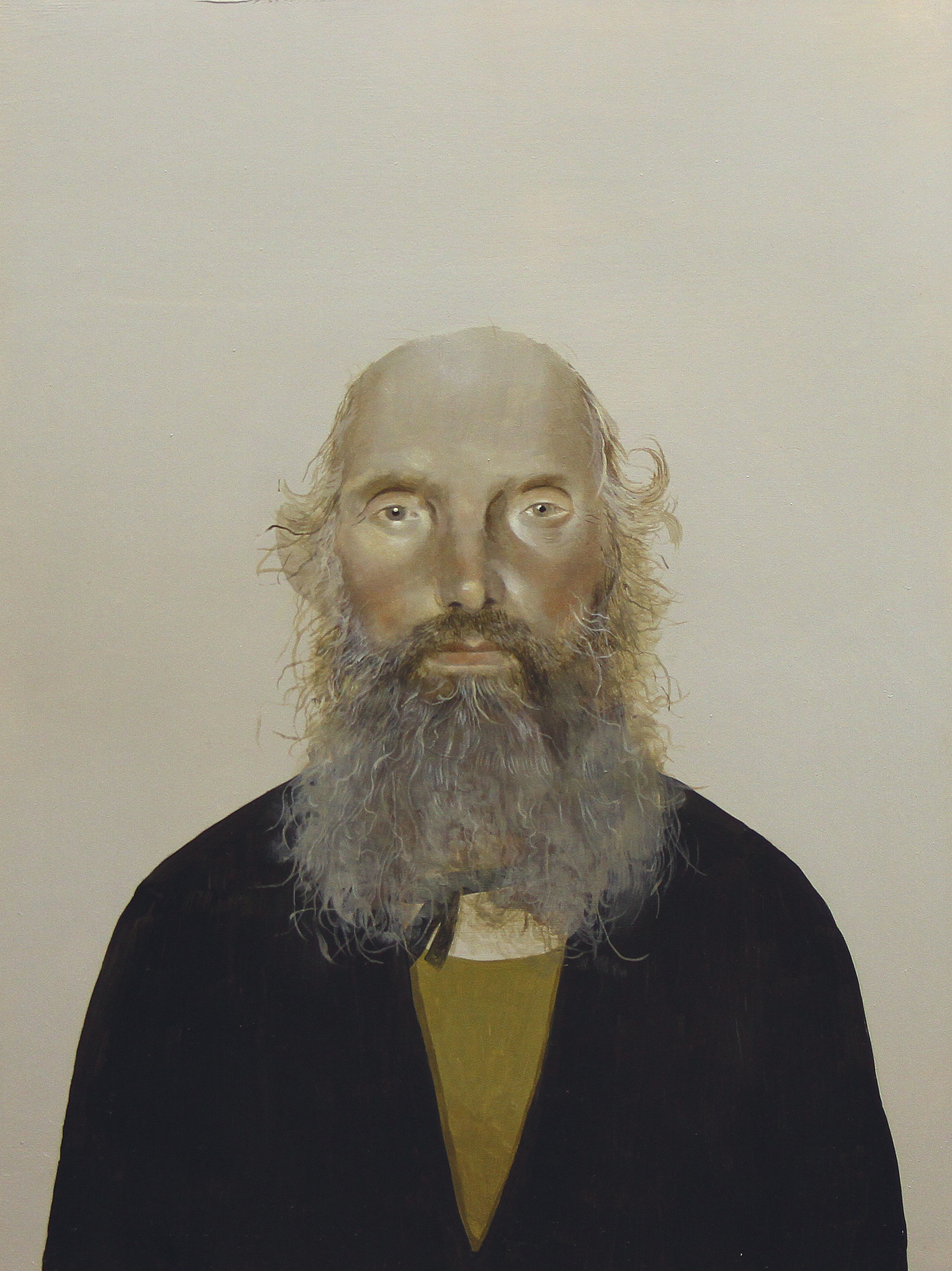

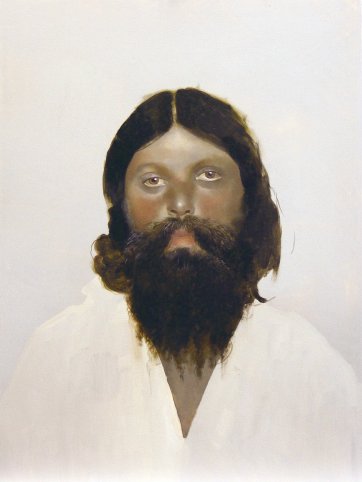

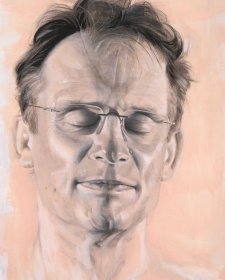

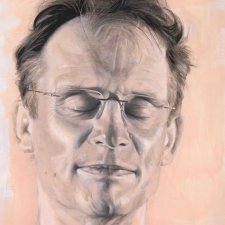

Greek Orthodox Priest, 2015 by Sarah Ball

Sarah Ball’s recent paintings generally depict people at a fateful juncture – but they do so at a distance. Over years, she’s pored over museum curios, Victorian taxidermy, collected objects and studio and police photography before recasting her sources, ‘creating new characters in imagined scenarios’, she says.

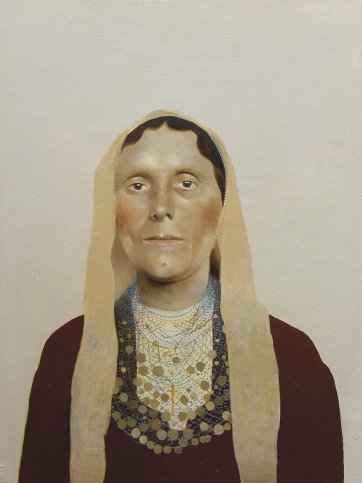

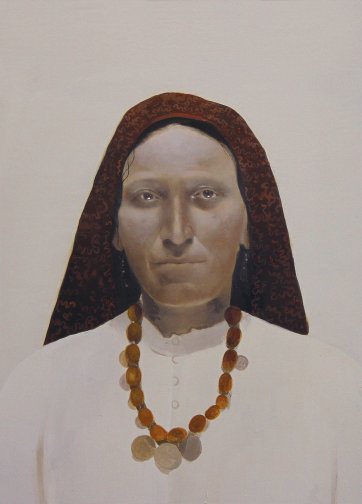

1 Greek Woman, 2015. 2 Italian Woman, 2015. Both by Sarah Ball.

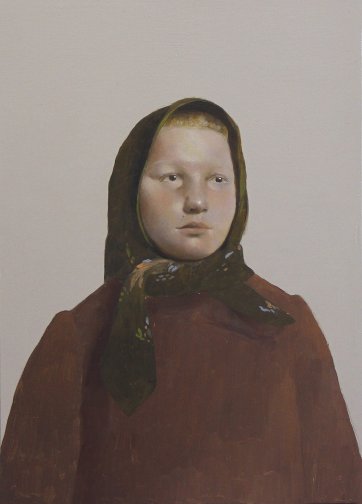

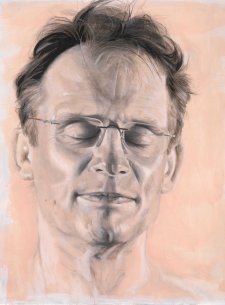

Born in Yorkshire in 1965, Ball has studied and worked in Wales and England; she now lives in Cornwall. Her tiny figurative ‘portraits’ have an unnerving quality of achronicity; it’s hard to tell when they were made. Many of the subjects wear national dress, which changes little over centuries, but their very faces seem old-fashioned, too. Had the people in the portraits been painted from life in their vague own time, we might have expected a different painting style; Cubist, perhaps. Right now, it’s hip to be dowdy and expressionless against a grey background. Yet Ball’s subjects seem frumpy without irony; unsettling for the reader of Frankie or Monocle.

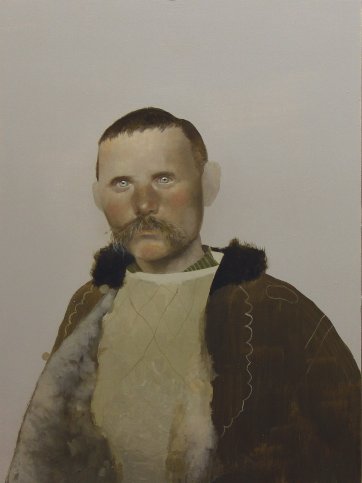

1 Roman Shepherd, 2015. 2 Czecho-Slovack, 2015. Both by Sarah Ball.

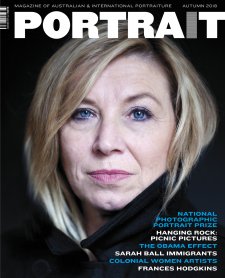

The artist based the works on these pages on photographs of immigrants, taken far away and long ago. Some are by Augustus F Sherman, a clerk in the US Bureau of Immigration, who between 1905 and 1920 took hundreds of photographs of new arrivals to the USA. In any given week, from his office at Ellis Island, he might have looked out at a queue of burdened men and women in headscarves and hats, big skirts and variously cut jackets. At best, it took them a few hours to be ‘processed’; if a person’s physical, mental or moral fitness was in doubt, there were delays. Quite often, evidently, Sherman darted out and photographed people awaiting their fate. Studied in 2018, Sherman’s photographs, like those of his contemporary Lewis Hine, are extraordinarily affecting as records of individuals pulled randomly from a ‘sea’ or ‘stream’ of apprehensive immigrants. Hine is better-known for photographs other than his Ellis Island series, but Ball has treated his photographs of immigrants, too.

1 Slovak, 2015. 2 Jew, 2015. Both by Sarah Ball.

Making her paintings of photographs of people, Ball proceeds in the opposite way from a faltering portrait artist who, having made a sketch or two from life, copies difficult passages from photographs. Ball discards details provided in her source images. In Sherman’s 1910 photograph, the Reverend Joseph Vasilon wears the rigid hat of a Greek Orthodox priest. In ‘recasting’ the named historical man as an anonymous one, Ball has removed his kalimavkion, made him bald, smoothed his wrinkles, fluffed his beard, softened his eyebrows (several subjects lack brows and lashes; they look more vulnerable without them). In Hine’s photograph, the ‘Czech grandmother’ has eyes of ice blue and a minimal slit of a mouth; by these features she’s instantly recognisable in Ball’s painting. The historical woman has a creasier face than her painted equivalent, though, and she wears a striped cardigan. Then again, the artist has favoured her with a countrywoman’s sonsy cheeks. Ball’s austere palette contrasts with recent colourised images of Sherman’s black and white photographs of immigrants, apparently based on careful research into traditional costumes of their homelands. Viewable online, they’re strikingly brighter and more varied in colour than Ball’s oils on canvas.

1 Syrian Arab, 2015. 2 Unknown, 2015. Both by Sarah Ball.

The artist delights in details of dress. Yet look closer at the paintings and it’s the variation in their planes and degrees of detail that’s striking. Take the Greek woman. Her coin necklaces and crucifix are really only indicated. Her body’s dead flat, her hair undulates like a piece of card around her high forehead, her head covering’s stiff as crêpe paper. The contours of her face, however, appear to be moulded from china clay. Framed by her gauzy cap and mound of hair, the Dutch girl’s cheeks are apple-like, her firm lips kissable, her chin plump. Her dress, meanwhile, is one-dimensional. We start at the vigour of the bright-eyed Romanian shepherd before registering his cursory ears.

1 Holland, 2015. 2 Russian Jew (Vegetarian), 2015. Both by Sarah Ball.

Much has been made of the contemporary relevance of Ball’s Immigrants series. Scrutinising Sherman’s and Hine’s images, we wonder whether the people in them prospered or failed. Another layer of humanity is embedded in Ball’s refined paintings. We sense the tact with which the artist addresses the strangers in the images; from her reclamation and adaptation, we infer care. I’m particularly compelled by an image Ball adapted from a Hine photograph: Jew. Her body a sack, her face meek and worried, the woman yet retains a trace of hope for kindness. Is that not the quintessential human hope: that someone will meet the eye, hold the gaze … and move closer?