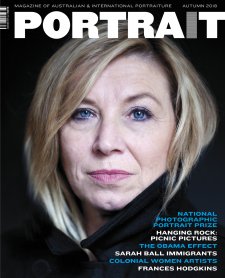

2018 sees the eleventh iteration of the National Photographic Portrait Prize, a perennial favourite among Portrait Gallery visitors. The process of deciding on this year’s winners – from a veritable cascade of entries – fell to tenacious trio Christopher Chapman (National Portrait Gallery Senior Curator), Petrina Hicks (contemporary artist who works with photography), and Robert Cook (Curator, Art Gallery of Western Australia). Here, arbiter Cook responds to questions from Portrait editor Stephen Phillips.

This year’s National Photographic Portrait Prize saw an unprecedented level of interest, with its 3,223 entries leaving the previous record – 2,804, from last year’s prize – in the shade. Can you tell us about the process of working through such a large number of entries, and the challenges it posed? How did you, Christopher and Petrina go about arriving at the final shortlist of 43?

Lord – It was H-U-G-E! Such an amazing response from the art and photo communities. It was overwhelming actually. I mean, as a curator, you know there’s only so much work that can fit on the walls in the exhibition, so your first response is practical – how to shrink it down to a manageable scale without losing any gems. You can’t fall asleep at the wheel! Rather, you can’t fall asleep at the mouse … because the wonderful Portrait Gallery team had set up this system where we individually went over the entries online. We each went through this first round separately with no idea what the other two were choosing. And, again, it began with the sense of a brutal yet necessary cull … but over time, you came to expect these little flashes of brilliance (that stood out from what was actually a uniformly impressive field), though often you don't know why, but still you find yourself, almost irresponsibly, clicking ‘accept’. Maybe it’s like Tinder or Grindr – with a slight thrill, you click fast and have a think later! So that’s how the first part happened: all very loose and, for me at least, intuitively, with always a sense of the looming mass!

After that stage we all met up for a couple of days in a sealed bunker in the Portrait Gallery basement. On a very large screen, we went through the work we had all said ‘yes’ to, and then the works that two of us had said ‘yes’ to, and then the works that only one of us had said ‘yes’ to. This was all very jovial, and the first time we had to suss each other out taste-wise. It was fun; but then it got really hard. The list was still huge, and now there were actual stakes – works we loved and didn't really want to part with … but, you know, WALL SPACE! So then the hard talking happened. We argued (politely) for and against individual works. Sometimes the arguments were cogent; other times, well, not so much. Often my big cry was for a pic that featured, say, a really good hairstyle. I don’t know why I liked it any more, but it brought the whole together for me, and I guess I was responding to style in a broad sense – as the thrust of a work, its ‘ambiguous togetherness’. I was not altogether amazing at putting that sense into words. Chris and Petrina were more articulate and super-sharp on other aspects too. Petrina looked as an artist honing in on composition, subject, technique – but also as animal lover (and as you know animals have often featured in her output over the years). It was a great privilege, in fact, seeing her at work. It’s corny but true: there really is something that distinguishes artists from the rest of us; it was compelling to listen to her take, and I felt I learnt about how she makes pictures in the process. With his experience as Senior Curator at the Portrait Gallery, Chris was very sensitive to how great portraits fascinate and communicate, both in terms of immediate punch and lasting resonance. He was also incredibly on top of the practices in general of the artists we were looking at, and was able to fill us in and give context to what we were seeing. Also, both Chris and Petrina knew who the politicians and culture stars in the photos were, unlike my news-phobic self, I’m afraid. They had a bead on how these figures were being presented, and how they resonated as icons.

So we were all different – through this process there was a lot of agreement, but also some stalemates. When we got stuck we left the room and went for coffee upstairs. Actually, there was lots of coffee! But after each double espresso our previously jittery nerves became focused anew, and we could see things a bit more clearly. And in the end, there were 43 works. One more than the meaning of life. Life, plus change. No wonder it was hard!