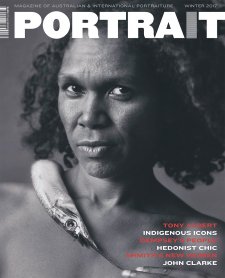

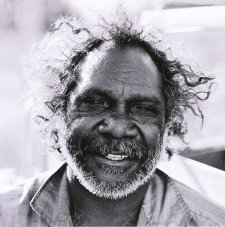

Ningali Lawford-Wolf (Ningali, Nagarra – through our customary law kinship structure) is my mother, and I Nyanyjili, am her daughter. We grew up in the same town, Fitzroy Crossing, together. I am incredibly proud of her achievements. She has taken life fiercely in her stride and brought the modern and traditional together within herself, and put it on show for us all to see. That is what this portrait says to me. It says: ‘I know who I am; I am a woman of now. My now is creative, energetic, and it is made up of many complex and brilliant parts.’ In this photograph, Ningali makes it very clear that there is no contradiction in keeping the past alive in our present. She does it with a glint in her eyes, which says ‘you may not believe me, but this is truth’. We are our histories and our ancestors, and the wisdom they have taught us is alive within us all. The fish gracefully resting on her shoulder is an image as modern today as it was 60,000 years ago. There is something incredibly intimate about how the fish rests across her chest and how her fingertips, with only the slightest of touches, keeps the fish poised, balanced and still. This shows us our very being as Aboriginal people – our profound connection to our heritage and the natural world around us.

This portrait brings Ningali to the stage, in a performance that is real, raw and beautiful. She is clearly holding the gaze of a transfixed audience. As a performer, Ningali is ablaze with energy in her determination to embody the resilience, the strengths and struggles of herself and our people. She has a remarkable skill to perform our world into being, to dance it into life, and to make it tangible for us all, in the most modern of contexts.

In Ningali’s stare, in the strength of her body, she holds her mother – a senior law and ceremony boss. All Ningali family are highly talented and skilled. The best performer is the one who sweeps us into the narrative with them. Ningali does that better than anyone I’ve witnessed. She makes us forget the veil between life and art. She weaves us into her stories so we see something more about ourselves and humanity.

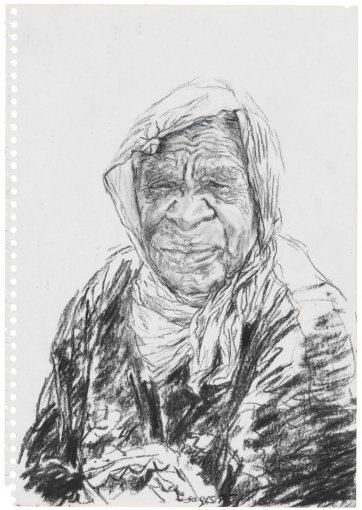

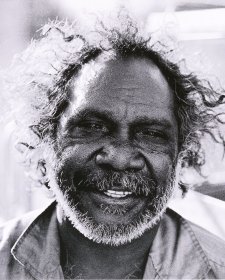

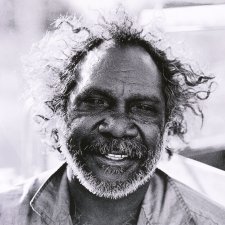

Marcia Langton is a true intellectual powerhouse. The clean, clear colours and lines of this portrait make me think of her sharp arguments; she strikes a wise pose in amongst the pastels and greys. Her words cut through the haze and confusion of discussion to make points of precision. Throughout my career, I have admired Marcia’s strong critiques on Indigenous policy issues and broader political affairs. As a community advocate, she made me believe that voices from the ground could have wide-ranging influences on policy and legislation. As I move into the national justice arena, it is people such as Marcia that give me the strength to believe in my convictions.