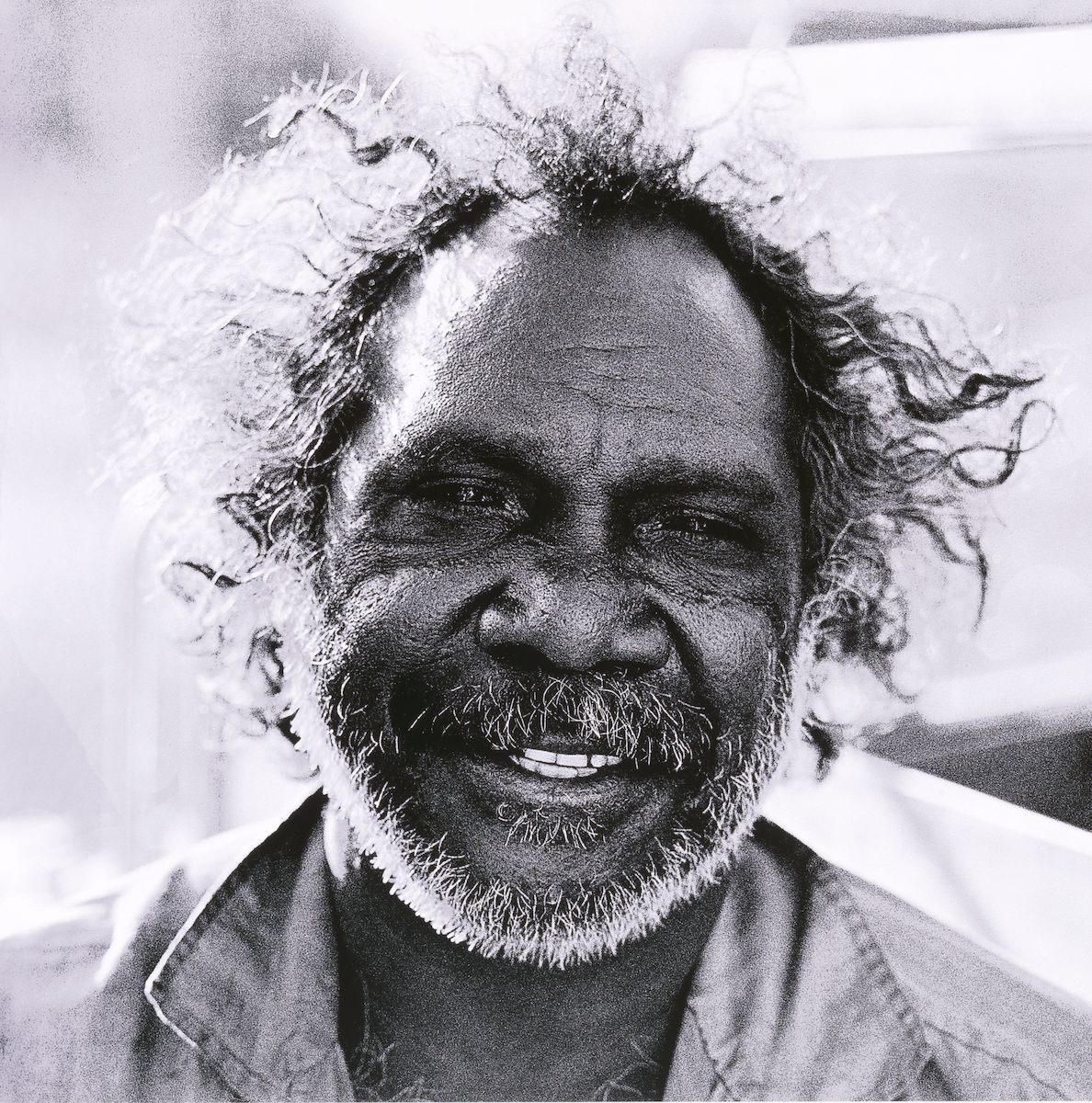

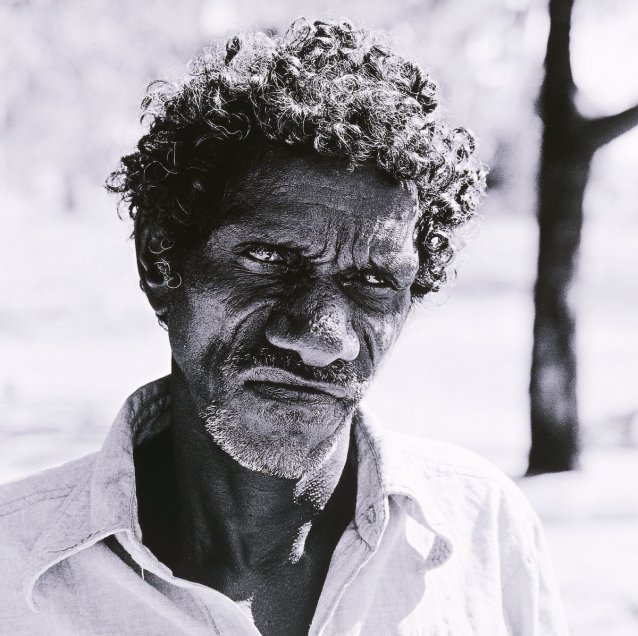

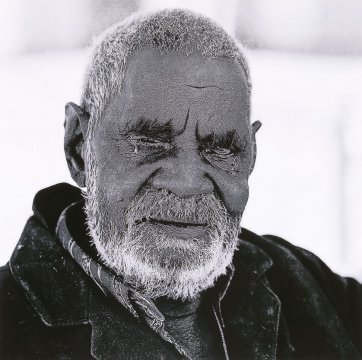

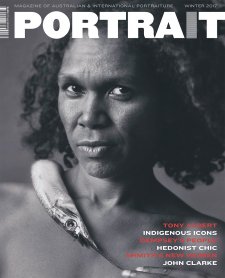

Wainburranga (Paddy Fordham), 1986 Martin van der Wal. © Martin van der Wal

‘White people don’t know Australia … we know it from the beginning.’

Paddy Wainburranga – Too Many Captain Cooks, 1988.

A portrait in Aboriginal terms is not an individual face, but a body painting-pattern-design – an image of the unchanging soul only seen in special moments. And, following the upright body shape, the image is taller than it is wide.

Many photographers have wanted to visit Ramingining artist community in Central Arnhem Land to complete their ‘classic’ essay for history – one could’ve come every day and driven everyone mad. Martin van der Wal came to make something for history, but different – for our history. He came to take particular people’s pictures; travelling with his partner Susie, he was quiet, reserved, and bonded well with everyone.

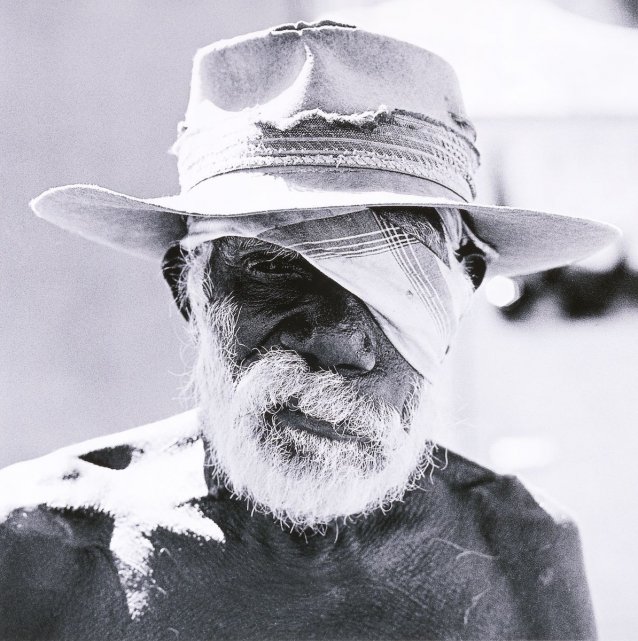

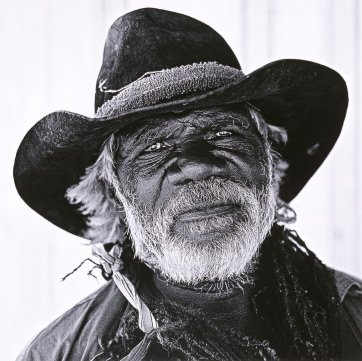

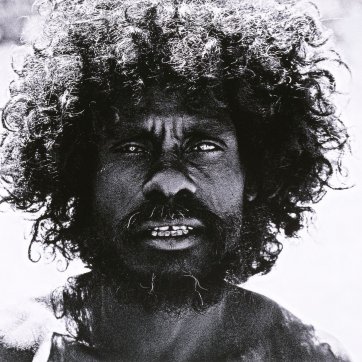

‘I wasn’t born yet … I was still in the water yet.’

Paddy Dhathangu, 1983.

Some Aboriginal people believe that waterholes, wells and springs contain the souls of unborn people. In 1986, the year of Martin’s visit, Elizabeth Jolley’s novel, The Well, won Australia’s Miles Franklin Award for literature. It tells of a well that possibly contains something dead, murdered, that whispers to the characters, haunting them. The Yolngu word mangutji or mel means waterhole, but also seed and eye. It is said that the eyes are the windows to the soul, so photographers often focus on the eyes to capture more of the character of the subject. In all Martin’s portraits, the subject’s eyes stare strongly back at the camera, fearless and in control of their image.

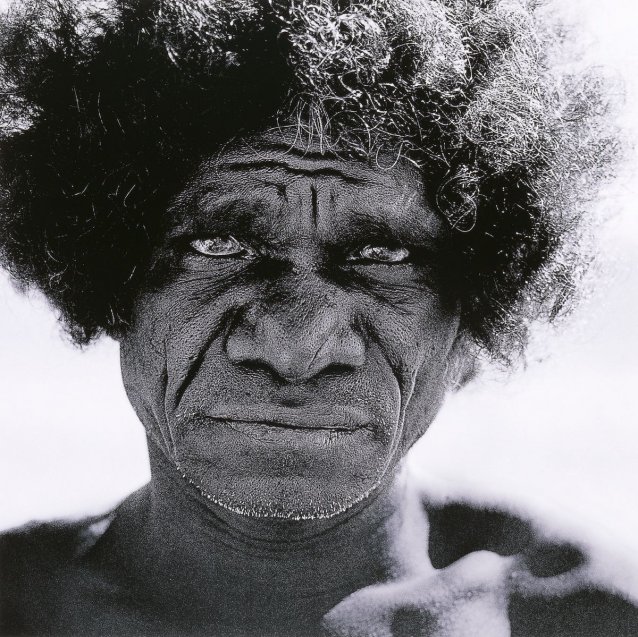

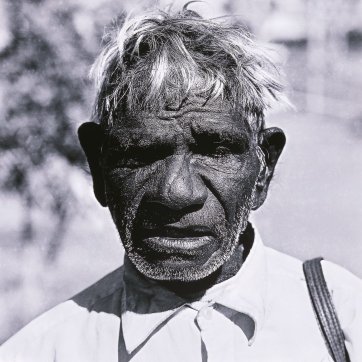

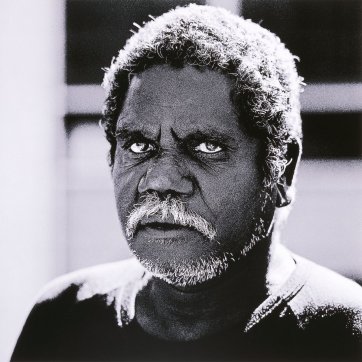

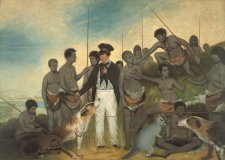

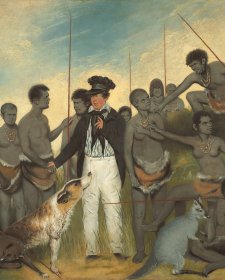

‘This place Sydney was once an Aboriginal place; there were Aboriginal people here. Then Captain Cook and Balandas (Europeans) came and pushed them out, but they are still here, one line, one blood.’

George Milpurrurru, 1986

A group of fifteen Aboriginal artists from Ramingining installed a low relief sand sculpture-ritual performance space in the 1986 6th Biennale of Sydney: Origins, originality + beyond. Led by the renowned bark painter George Milpurrurru, we battled through the week or so of the circus that these events are. We met many international artists and other Aboriginal artists, like painter Michael Nelson Tjakamarra, and many local Aboriginal people, prompting George’s remark. The Indian weaver-artist Mrinalini Mukherjee, whose wonderful woven jute mythical figure pieces we’d noticed, came to Ramingining shortly thereafter to see the artists in their ‘studios’.

That year was an active one for the artists and the community. Local identity, actor David Gulpilil, had been part of the film Crocodile Dundee, and this was released that year. The Aboriginal film The Fringe Dwellers was also released that year.

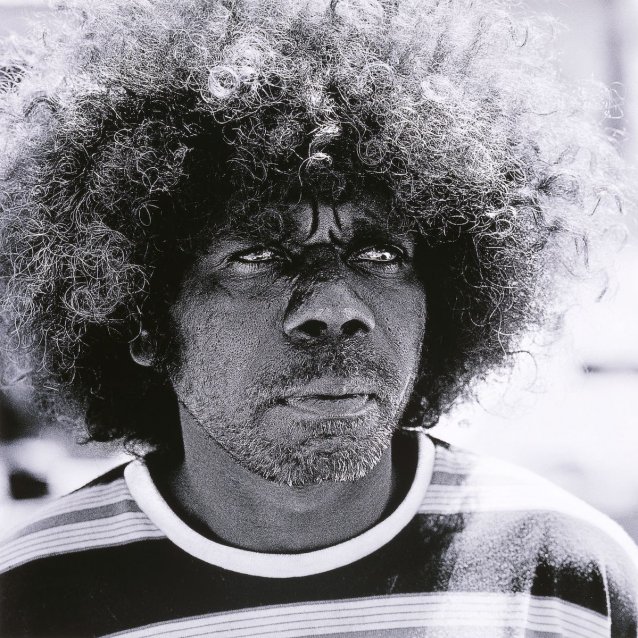

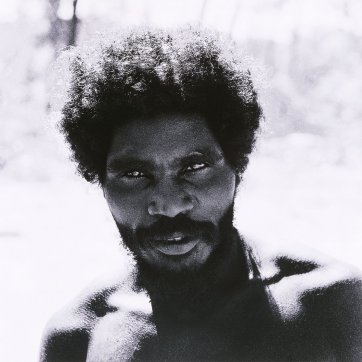

‘My name really means tortoise.’

John Bulunbulun, 1983

Johnny Bulunbulun worked meticulously and methodically on his paintings, each one taking an extended length of time. By 1986 he’d already had what was probably the first solo bark painter exhibition ever (in 1982), and was much sought after. His mother – the fine weaver Mary Milngurr, who Van der Wal also captured in a portrait on this visit – lived in Ramingining, so Johnny was a familiar visitor; his ‘country’, containing a tortoise sacred site, was nearby.

‘My painting was different to my father because I lived in mission times. Many of these old people didn't paint much [commercially] but were mostly doing ceremonies.’

David Malangi

The artist co-operative held many sophisticated people. David ‘Dollar Dave’ Malangi was one – a convoluted path led to his painting being printed on the first Australian one dollar note. His artwork was then much sought after. Milpurrurru and Malangi, with Johnny Bonguwuy – all from Ramingining – were the first three Aboriginal artists to be in a Biennale of Sydney – the third – European Dialogue, in 1979.

‘A sorcerer can do things with it. When the tree branches rub in the wind, it makes a sore throat. Soon you’ll feel like you’re being choked to death.’

Philip Gudthaykudthay (The Sorcerer) – Ten Canoes 2006

Milpurrurru and Malangi, along with Paddy Dhathangu and Paddy Wainburranga, would join forty-three artists (mainly from Ramingining) in 1988 in constructing the Aboriginal Memorial for the 7th Biennale of Sydney – From the Southern Cross: a View of World Art c1940–1988.

1 Rover Thomas, 1986. 2 Jarinyanu David Downs, 1986. 3 James Iyuna, 1986. All Martin van der Wal.

© Martin van der Wal

All these artists were sophisticated, much-travelled human beings. In 1988 Malangi and Wululu travelled to the important Dreamings exhibition at the Asia Society Gallery in New York, where their work was to feature. One day in Central Park, Wululu observed ‘This was all Indian land once’. A set of fifteen of his white herringbone-patterned poles (representing the bones of the totemic catfish) would be included in the 1989 Magicians of the Earth exhibition in Paris, one of the most significant exhibitions of the 20th century.

1 Paddy Jaminji, 1986. 2 John Mawurndjul, 1986. 3 Jimmy Wululu, 1986. All Martin van der Wal.

© Martin van der Wal