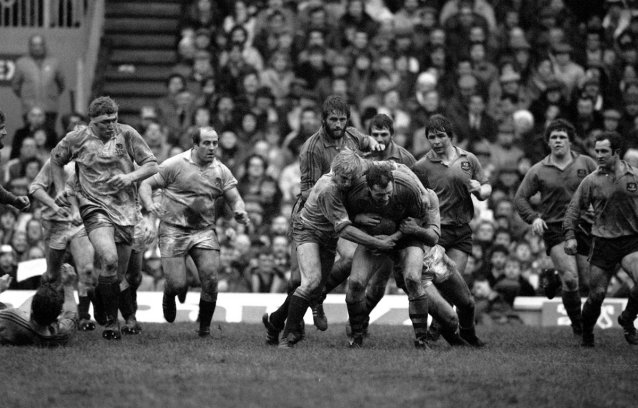

Richard Burton would rather have played for Wales at Cardiff Arms Park than played Hamlet at the Old Vic. Military service got in the way of a rugby Blue at Oxford. He played for the RAF side, alongside the future captain of the Welsh Dragons, Bleddyn Williams, who wrote in his memoir that Burton had the potential to be a first-grade player. The Oxford Dictionary of Biography describes Burton as sturdily built like a rugby half-back; however, the parallel careers that the entry documents were not to be those of a rugby-playing thespian. Rather, it was the chronicle of the Hollywood star who also trod the boards of London’s biggest stages.

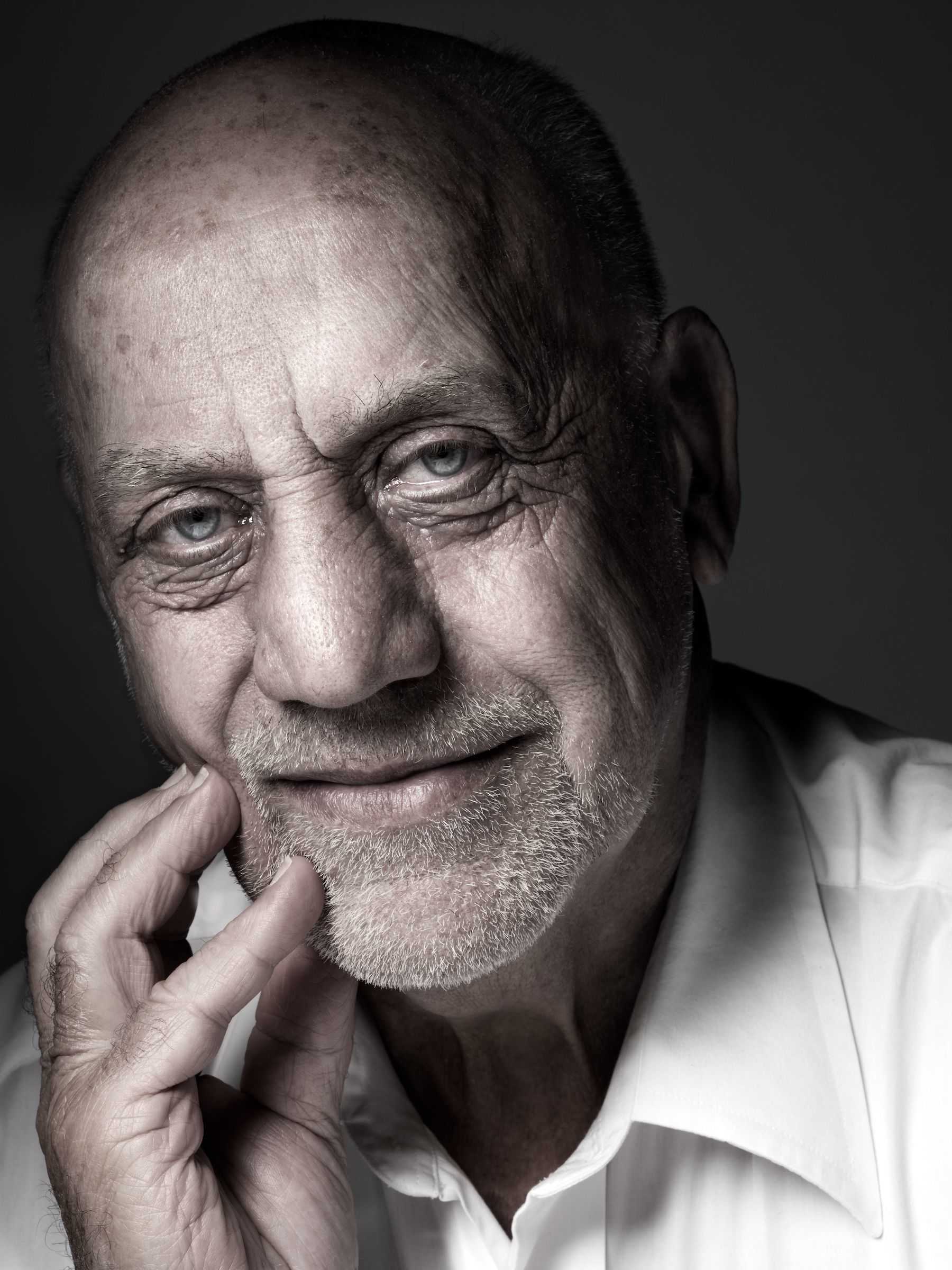

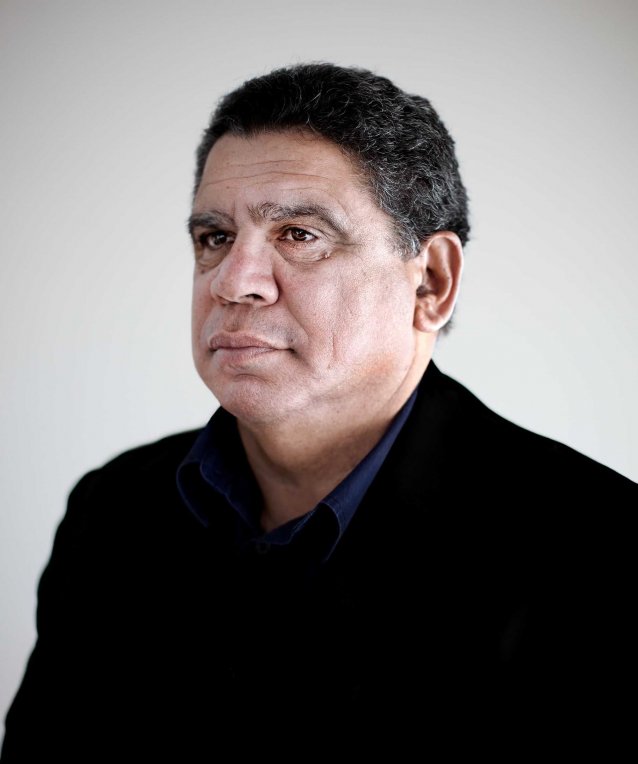

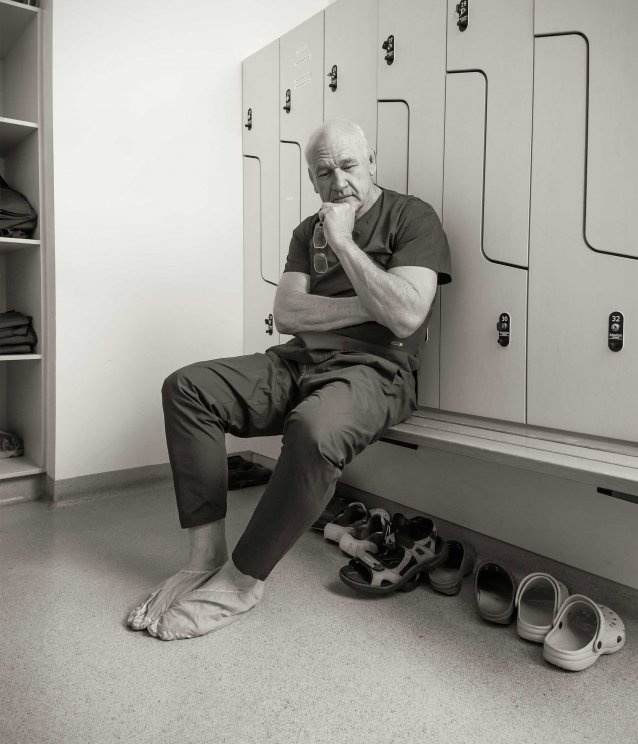

Sport generates past lives. With the exception of perhaps snooker (Fred Davis obe played from 1929 to 1993), no sport allows competitors to stay on top forever. Eventually life after sport must begin, and that time spent on the field or court becomes a reference point in a life. The portraits of three former captains of the Australian rugby team have recently been added to the National Portrait Gallery collection: Ken Catchpole OAM by Sydney-based advertising and portrait photographer Gary Grealy; Mark Ella AM photographed by Scottish-born artist Nikki Toole; and Mark Loane AM by Berlin and Brisbane-based contemporary art photographer Joachim Froese. The reference point is the here and now. The portraits show no trace of past lives – they are photographs of the men as we meet them today.