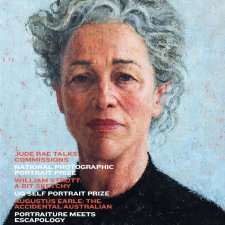

A biennial, acquisitive award that sets out to highlight the continued relevance of self-portraiture, the University of Queensland’s National Self-Portrait Prize (NSPP) questions the assumption that we as individuals are best represented by our physical features. Faced with the challenge to create a self-portrait, an artist decides what most clearly represents the essence of self – a visual image that best indicates to others that essential, distilled self.

The winner of the 2015 NSPP was Melbourne artist Fiona McMonagle for her work One hundred days at 7pm. The exhibition and prize has been presented by Queensland University Art Museum every two years since 2007, and this is the third time the prize has been awarded to a digital media work, albeit, in this case, one derived from a hundred hand-painted watercolours. Inclusion in the prize exhibition is by invitation only, and the 2015 exhibition Being and Becoming was selected and curated by freelance curator, Michael Desmond. The prize was judged by Jason Smith, Curatorial Manager of Australian Art, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.

Recognising the limitations of the single captured moment, Fiona McMonagle set out to paint a self-portrait in watercolour every day for a hundred days. As she wrote in her artist’s statement: ‘I wanted to translate these ideas about time and change into this work. So, I painted one self-portrait every day at 7pm for 100 days.’ The hundred portraits are presented as a looped 16-second video animation. McMonagle set herself strict rules, limiting the palette and medium to an almost monochrome set of watercolours, painting one work every day in the studio at 7pm, and not looking at the previous works before starting each evening. Best known for her delicate watercolour portraits of suburban youth, this work is a beautiful and successful realisation of the exhibition’s central theme of ‘becoming’, and an interesting and unexpected extension to her art practice. That said, the artist’s intention to reflect change through time is partly negated by the fact that each image is derived from stills of a single video recorded on the first day of the project.

Although the University of Queensland Art Museum has invited different external judges each year, this is the first year they have entrusted the selection to a curator not associated with the museum. Michael Desmond, previously Senior Curator and then Assistant Director of the National Portrait Gallery, has chosen what at first appears to be a very eclectic group of thirty artists. In a video statement on the museum’s website, Desmond explains that the strongest influence on his selection process was an intention to balance artists with a lot of life experience with those with less life experience, encompassing a contrast between younger and older artists’ responses to the ideas of change and ‘becoming’.

Whether intentional or not, the exhibition not only strikes a balance through consideration of the artists’ ages, but also of their gender and cultural backgrounds. Desmond invites us to further question how the notion of self might be a reflection of a range of variables; this includes elements such as the experience of ageing for different genders, the experience of artists who identify with their Indigenous heritage, or those born overseas and growing up in a different culture, or those born in Australia but with parents from another country.

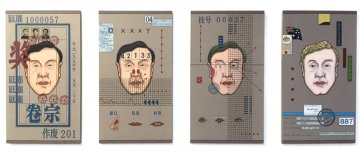

In a series of four paintings, Plastic surgery, Chinese-born artist Guan Wei humorously documents the pressure to fit in, or ‘becoming’, from Chinese born Guan Wei to Australian citizen, David Guan. By documenting his new Australian identity with reference to his passport, his bank account, his Medicare card and his ABN number, he is still, as he was in China, a series of numbers in an official government record. Similarly, Lindy Lee, born in Australia to Chinese parents, speaks about the split identity that results from belonging to two different cultures, in her work Threshold between two unknown territories. Lee’s large photographic self-portrait is printed on a steel sheet pitted with random holes burnt into the support, but appearing like splashes from an excessively strong acid. She depicts herself as a Zen master staring out at us with a face of benevolent calm, but the image is devoid of colour and lit with the stark chiaroscuro lighting of a Rembrandt or Caravaggio. Lee has recently begun using these burnt holes in the surface as an extension of her ‘splash’ paintings, derived from the traditional practice of Zen Buddhist Monks who splashed their paintings with ink to portray the universe’s energy and the impermanence of all things living and created. In contemplating the essence of self, Lee understands the futility of always trying to ‘fit in’ and comes to terms with just ‘being’. As she writes in her artist’s statement, ‘After years of meditation I realised that there is no single self to strive for or hang on to. This self-portrait invokes the thresholds of constant becoming that lie between the past and the future.’

In three photographic works by Indigenous Australian artists, the self is again defined as a product of two histories and two cultures. Andu (Son) by Michael Cook, School’s in by Fiona Foley and On becoming by Christian Thompson all address the issue of racial difference and the feeling of both belonging and not belonging to two different peoples. Michael Cook superimposes his European features over an image of a member of the Aboriginal side of his family. Fiona Foley leans her body against an ancient tree next to a wooden chair representing her school years and memories of her fears of being singled out as different. Christian Thompson hides his European features behind hands decorated in his ancestral cross-hatching style.

Self-portraits are, by definition, self-examinations. They are a chance to reflect on not only who you are, but also how you are going in that journey of life experience. We tend to believe in the honesty of an artist’s self-portrait more if it is flawed than if it’s perfect. We believe that we would recognise Van Gogh or the ageing Rembrandt if we passed them in the street, but would perhaps be disappointed meeting Rubens or Durer. One of the most honest self-portraits in this exhibition is by the oldest of the thirty artists, Janet Dawson, who has depicted herself with a series of images of a smiling cabbage that began as a private joke between the artist and her husband. They created the ‘face’ of the cabbage in 1992 using toothpicks, olives and other organic materials, before replanting it and documenting its decomposition over several months. Now, over twenty years later, she playfully recognises this smiling face in her reflection in the mirror: ‘I found it somewhat comical being faced with the prospect of making a self-portrait at the age of eighty. So, I have mixed in the life and death of the smiling cabbage with a rueful examination of my aged self.’

This notion of coming to terms with yourself and with what birth and life has dealt you is also evident in the work of one of the youngest artists, Tyza Stewart, born over half a century after Dawson. Stewart’s portrait, Exit tunnel, is presented in two parts; first there is a full-size portrait questioning our notions of conformity, by depicting a body manipulated to appear gender non-specific. The second part is an L-shaped wooden tunnel whose height and width are built to comfortably allow the artist to walk in. At the end of the tunnel is a rectangular slit like the eye-opening in a Muslim niqab that ‘may allow a viewer to be alone and hidden while they observe artworks and people in the gallery’. While inviting the viewer to explore the tunnel, comparing their own dimensions to those of the artist, there is also the suggestion of inviting you to imagine yourself looking out from within someone else’s body.

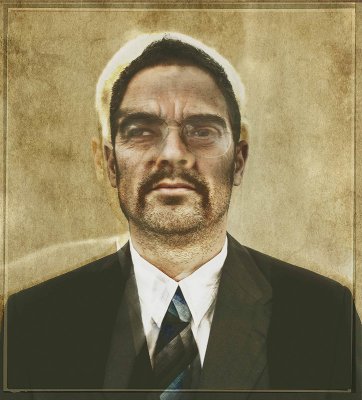

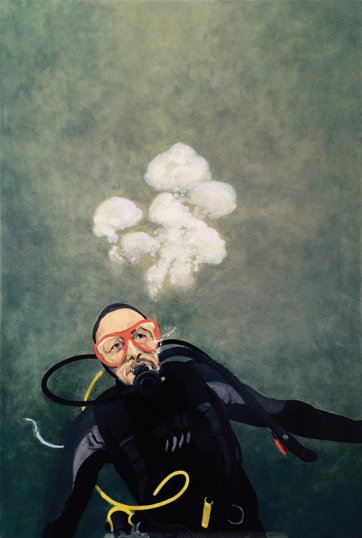

One of the most poignant self-portraits, and perhaps the most honest, is Self-portrait: Man re-enters the sea by Andrew Sayers, who was battling cancer while producing the artwork, and tragically died a month before the exhibition opened. Sayers had only recently debuted as an exhibiting artist, following a distinguished career as a curator and arts administrator. He was the inaugural Director of the National Portrait Gallery and the judge of the first National Self-Portrait Prize in 2007. Choosing to depict himself scuba-diving underwater references the cycle of birth and death, with all life starting in the sea; as he explains in his statement, ‘the unique marine environment gives me the opportunity to express a personal and essential truth: that we are all dependent upon the cycle of breath that is so tangibly visible underwater’.

While there is a chance a member of the public might recognise these artists if they stood next to their portraits, this is not the case with all the works in this exhibition. Since the late 1970s, Melbourne artist John Nixon has been painting and constructing non-objective artworks reminiscent of the works of the early 20th Century Soviet artist, Kasimir Malevich, and many of these works have been exhibited under an umbrella title of Self-portrait (non-objective composition). Nixon’s artworks are always roughly painted and frequently incorporate found utilitarian objects or scrap pieces of wood. Despite their uncompromising avoidance of ‘professional finish’, they all have an almost mysterious elegance that is inimitable and instantly recognisable as a work by John Nixon. For this exhibition, Nixon has painted Self portrait – N, a square canvas painted with his signature orange enamel, a colour chosen in the 1990s because no other artists were known for using orange as a predominant colour. Attached to the canvas are three pieces of unpainted timber, like off-cuts from a hardware store, arranged as a letter ‘N’. For an artist like Nixon, who has expounded a singular vision that has become an identity in itself over several decades, the essential ‘Nixon’ instantly recognisable in this new work is perhaps a more accurate portrait of the artist than any imitation of his facial features could ever be.

It could be argued that all art reveals an aspect of the artist, and collectively a lifetime’s accumulation of artworks make a detailed and multi-layered self-portrait. In two installations, Judith Wright’s theatrical The things we do and Julia De Ville’s gothic Ostara and Damocles both reference elements of their personal history, suggesting that our life’s experiences and collected memories are more essential as a representation of ourselves than a depiction of the shell in which we house our thoughts. Wright depicts an old mannequin standing on a film canister, referencing the movie theatre her father had when she was a child. Behind the mannequin rises a wood tree bearing biomorphic ‘fruit’, representing her children and grandchildren. De Ville, born four decades after Wright, has developed an artist’s persona inseparable from the work she produces. She has created a hybrid world of happy fantasy that is dressed in the macabre theatrics of the Victorian fascination with death. Her self-portrait installation consists of a taxidermied raven ominously suspended over a glass coffin containing a child/doll she made herself, at the age of eleven. Both installations are like dreams, giving us an insight into the ‘real’ artist, and to be read like a psychologist might interpret a dream.

Many of these works go beyond a traditional portrait that attempts to sum up the physical features and the personality of the sitter. Such portraits invite an intuitive reading of facial features and personality traits gleaned from the sitter’s cloths and setting. However, these artists are given the chance to convey themselves through more than appearance and are digging deep into their psyche to reveal an inner essence. The University of Queensland’s fifth National Self-Portrait Prize does emphasise the continuing relevance of the self-portrait as a genre. By shrewdly selecting artists to submit work for the exhibition, and allowing each artist the freedom to interpret what constitutes a self-portrait, this biennial exhibition and prize continues to be both surprising and exciting