The play thrust the style of European naturalism into an Australian setting. Not unlike the American dramas of Arthur Miller in the forties and fifties, The Doll took the model of the socially conscious dramas of European naturalism and co-opted them to a local setting, authentically exploring ordinary people in their own milieu.

For sixteen years, on their annual five-month layoff from cane cutting in North Queensland, Roo and Barney have lived with two barmaids, Olive and Nancy, in Melbourne in the Carlton boarding house run by Olive’s widowed mother, Emma. Roo gives Olive a kewpie doll each year when he arrives. In this seventeenth year, Nancy has married and been replaced in the quartet by Pearl, a widowed barmaid and colleague of Olive. Unbeknownst to Olive, Roo has quit and plans to stay in Melbourne. The changing times hit Olive hard.

A parable of youthful dreams coming into harsh collision with the realities of changing times and ageing, Olive’s treasured memories of sixteen summers of carefree love and good times come into brutal relief under Pearl’s more sceptical eye, and the realities of Roo’s diminished physical capacity, which has been directly challenged by a younger, fitter ganger, Johnny Dowd. The previously inseparable Roo and Barney find their once solid mateship splintering under the pressure. The simmering tension between them culminates in a bruising fight in the living room, during which the seventeenth doll, symbol of the cherished layoff season, is smashed. In the final shattering scenes, Roo, now a worker in a local paint factory, proposes to Olive. She recoils in horror and rejects suburban marriage. Devastated, she picks up her handbag and goes to work. Barney and Roo, supporting each other once more, leave the Carlton house forever.

Commentary on the play has often considered Olive’s refusal of Roo’s proposal as a failure to come to terms with reality, and an immature response. More recently, Olive has been described as a woman with a vision of a different reality, one in which settling for a suburban marriage and leaving work to be a housewife is not imaginable. Either way, the loss for all the characters is terrible.

In 1956, after the stellar season in Melbourne, each performance of the three-week season in Sydney was sold out, after which the Trust sent the play on a tour of Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth, Hobart and Launceston, followed by the regions. Sixty country towns in New South Wales and Queensland were visited in the following three months. Indeed, demand was so strong in 1956 that several additional companies of actors were formed, and they toured the play concurrently. It was reported in the Companion to Theatre in Australia that ‘people drove hundreds of kilometres and a man swam a flooded river to see it in the Northern Territory’.

None other than Sir Laurence Olivier invited the play to tour to London, saying, ‘It’s a damn good play. It’s as simple as that. Good plays are not easy to find.’ The Oliviers, Sir Laurence and Vivien Leigh, had conducted their own royal tour of Australia in 1954, and contributed financially to the refurbishment of the Newtown Theatre in which The Doll played. A youthful and handsome Richard Pratt joined the Doll company tour to London as the young gun Johnny Dowd, threatening the supremacy of the ageing Roo in the Queensland cane cutting gang. The play won a best new play award for its season at the West End.

The New York season was less successful, closing after five weeks. One can speculate about the specificities of the Australian dialect being lost on an American audience, but equally, more familiar with a diet of Miller and Tennessee Williams, perhaps the play seemed less revolutionary in America than it did in England, where critics noted the respect for working people provided a salutary lesson for homegrown dramatists. Nevertheless, Hollywood produced an adaptation in 1959 starring Ernest Borgnine, Anne Baxter, Angela Lansbury and John Mills, called Season of Passion, in which the characters approach their Carlton residence by travelling on a ferry on Sydney Harbour after a night out at the Easter Show.

The film version also has a ‘happy ending’, with Olive acquiescing to Roo’s proposal of marriage as if this was what she’d aspired to for seventeen years. The only member of the Australian cast in the movie was Ethel Gabriel, who performed the role of Emma to acclaim.

The Doll has been translated into many languages, was adapted to an opera, and in 1977 the Melbourne Theatre Company commissioned Lawler to write two prequels, Kid Stakes and Other Times, which became known as The Doll Trilogy.

Though many feared that the trilogy would dampen the impact of the beloved Doll, it is generally agreed that the two prequels penned by Lawler over twenty years later served to deepen our affection for, and understanding of, the characters in the original play. The Doll retains its ineffable power and hold on audiences.

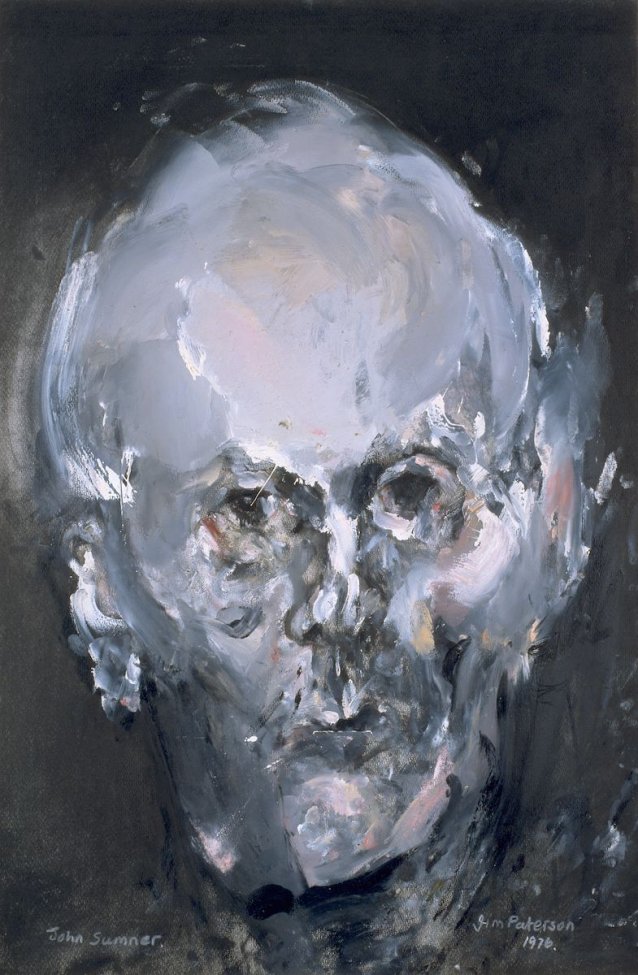

When asked recently about whether he tires of talking about his best-known work, the now ninety-four year-old Lawler gracefully responded: ‘Let’s be honest at least; I think any writer is lucky to have one play or one book that people like; it’s wonderful.’