Her ready wit and intelligence allowed her to take advantage of any opportunity that was offered to highlight an issue or drive a point home. One such instance occurred when she was part of a deputation meeting Prime Minister Menzies, who was happy to see Oodgeroo but very resistant to the idea of holding a referendum on constitutional change. Being a hospitable man he offered a drink to Oodgeroo, who cheekily reminded him that in the state of Queensland he would be committing a crime, as it was illegal to ‘provide spirituous liquor to an Aborigine’, deftly demonstrating how conditions for Aboriginal people varied dramatically from state to state. Menzies resisted all attempts at persuasion, and it was not until Harold Holt became Prime Minister that a referendum was held and Sections 51 (xxvi) and 127 of the constitution were changed, allowing the Federal Government to make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and including them in the population count.

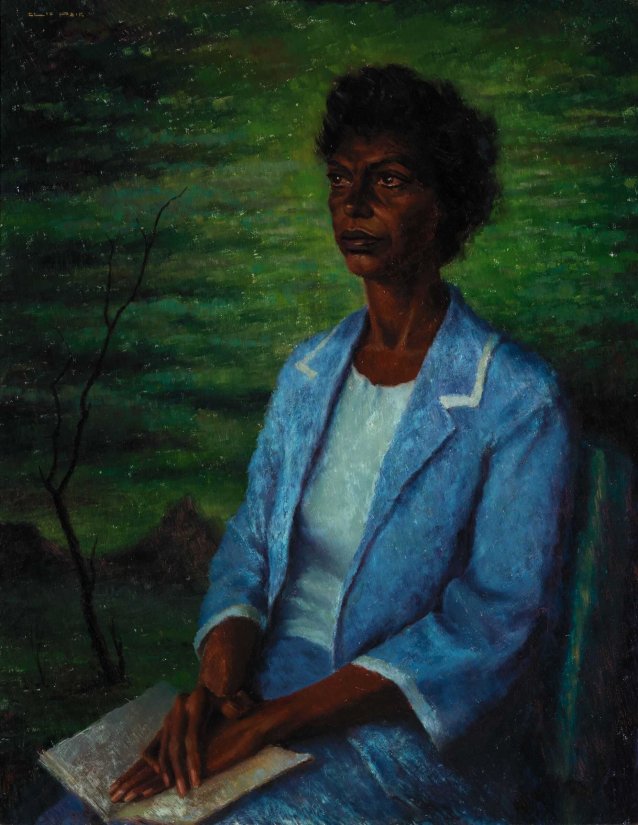

Clif Peir’s portrait, Kath Walker, Aboriginal Poet 1965, was painted during this period of Oodgeroo’s life. He adopted a traditional approach to depicting a writer, including an open book with Oodgeroo in a quiet reflective mood, gazing intensely into the distance as if in deep thought. Although based in Sydney, from the 1950s Peir travelled extensively throughout central Australia and became known for his depictions of desert landscapes. He was a great admirer of Oodgeroo, or Kath Walker as she was known then, and asked to paint her portrait; when she agreed, he invited her to stay at his home in Oatley while he did so. The portrait was hung in the 1965 Archibald Prize. Peir also demonstrated his interest in the conditions of Aboriginal people in another, more practical way through the donation of several of his artworks to the ‘Art Sale for Land Rights’ at Paddington Town Hall in 1970. The fundraiser provided support to Aboriginal Land Rights Councils in New South Wales, North Queensland and the Kimberley.

Seventeen years later, the two portraits by Juno Gemes present a different side of Oodgeroo. Gone is the neat Chanel-style suit, swapped for shorts and t-shirt, and she appears much more relaxed. She is at home, at the door of her caravan in one and sitting down inside it in the other. She is also very comfortable with the photographer, for Gemes had been involved in the protest movement for Aboriginal rights over several decades, as a participant, and also recording the movement and the key players within it.

Oodgeroo’s home or ‘sitting down place’, Moongalba, near Amity Point on North Stradbroke Island, is the inspiration of much of her poetry and where she established the Noonuccal-Nughie Education and Cultural Centre, the site of her great education campaign, encouraging children from across Australia to visit her in order to learn about Aboriginal culture and tradition. Over several decades, 30 000 school children visited her and were captivated by her vivid storytelling, gathered round the campfire. Some of these stories are included in Stradbroke Dreaming (1972), a combination of stories of growing up on the island and traditional storytelling, often imbuing lyrical descriptions of country with a moral message, the tales setting down guidelines on how to survive in the bush. Children weren’t the only visitors; teachers were always guaranteed a warm welcome, as were academics from across the world. Oodgeroo advocated that all Australian children should be taught about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture.

Oodgeroo’s t-shirt indicates that although she had retired to Stradbroke Island in 1971 she continued to be involved in campaigning for Aboriginal rights. The t-shirt design was created for the protests for Aboriginal land rights that occurred in Brisbane during the Commonwealth Games of 1982. A selection from Gemes’ extensive photographic archive formed the 2003 exhibition, Proof: Portraits from The Movement 1978 – 2003 at the National Portrait Gallery, and although Oodgeroo could easily have been included in the areas showcasing ‘The Political Activists’, ‘The Persuaders’ or ‘The Writers’, she was featured in the section dedicated to ‘Land Rights Before Games: National Land Rights Action’.

Although based on Stradbroke Island, Oodgeroo travelled widely, in demand as a speaker both in Australia and abroad, including Nigeria, India, the United States (on a Fulbright scholarship), and as part of a cultural delegation to China with Manning Clark. She was awarded honorary doctorates by four Australian universities, and an MBE, which she eventually returned in 1988 in protest at the Bicentennial celebrations.

That same year she changed her name from Kath Walker to Oodgeroo (meaning paperbark), of the tribe Noonuccal, affirming her pride in her Aboriginal heritage and her recognition of the power of language to shape thought.

George Fetting’s portrait was taken in the year before Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s death from cancer, in 1993. Living in Brisbane at the time, Fetting had the idea for an exhibition of photographic portraits of remarkable women, and Oodgeroo was one of the women he approached. He travelled to her home and spent a day photographing her. The result is larger than life, with the 110 x 88.2cm print taken up by Oodgeroo’s face, framed by her left hand. Her gaze is steady and solemn, looking into the distance, and every pore of her face and the smallest crease on her hand can be seen. Fetting describes portraiture as his ‘first love’, and in this instance he has created a compelling work, with rich tonal range and quiet intensity, conveying strength and solemnity. In this portrait, Oodgeroo Noonuccal appears every inch the matriarch of a community she has gathered around herself.

The final word should be given to Oodgeroo, who, in her interview with Hazel De Berg in the oral history collection of the National Library of Australia, stated ‘… one day I sat down and thought, I’m sick of answering questions, I’ll write a poem about who I am, what I am, and why I am what I am. The poem is called The Past.’ In it, she ponders the relevance of what has gone before and how it continues to weave through the present and into the future. She continues to challenge us all to be aware of past events and remain cognisant of the limitations of the present, while working towards change and a new and better reality.

The Past

Let no one say the past is dead.

The past is all about us and within.

Haunted by tribal memories, I know

This little now, this accidental present

Is not the all of me, whose long making

Is so much of the past.

Tonight here in suburbia as I sit

In easy chair before electric heater,

Warmed by the red glow, I fall into dream:

I am away

At the campfire in the bush, among

My own people, sitting on the ground,

No walls about me,

The stars over me,

The tall surrounding trees that stir in the wind

Making their own music,

Soft cries of the night coming to us, there

Where we are one with all old Nature’s lives

Known and unknown,

In scenes where we belong but have now forsaken.

Deep chair and electric radiator

Are but since yesterday,

But a thousand thousand camp fires in the forest

Are in my blood.

Let none tell me the past is wholly gone.

Now is so small a part of time, so small a part

Of all the race years that have moulded me.

by Oodgeroo of the tribe Noonuccal, from My People 3/e, The Jacaranda Press, 1990. Reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons Australia.