There are a handful of couples represented in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. Some are represented as individuals, as in discrete works depicting Gough Whitlam, Margaret Whitlam, Dymphna Clark and Manning Clark.

Some appear together in the same work, as in the photographs of Thomas Sutcliffe and Eliza Mort, Loti Smorgon and Victor Smorgon AO, and Linda Burney MLA and the late Rick Farley. Complementary large portraits depict industrialist Sir Edward Knox and Lady Knox, and there are two tiny, gay miniatures of architect Mortimer Lewis and Mrs Lewis.

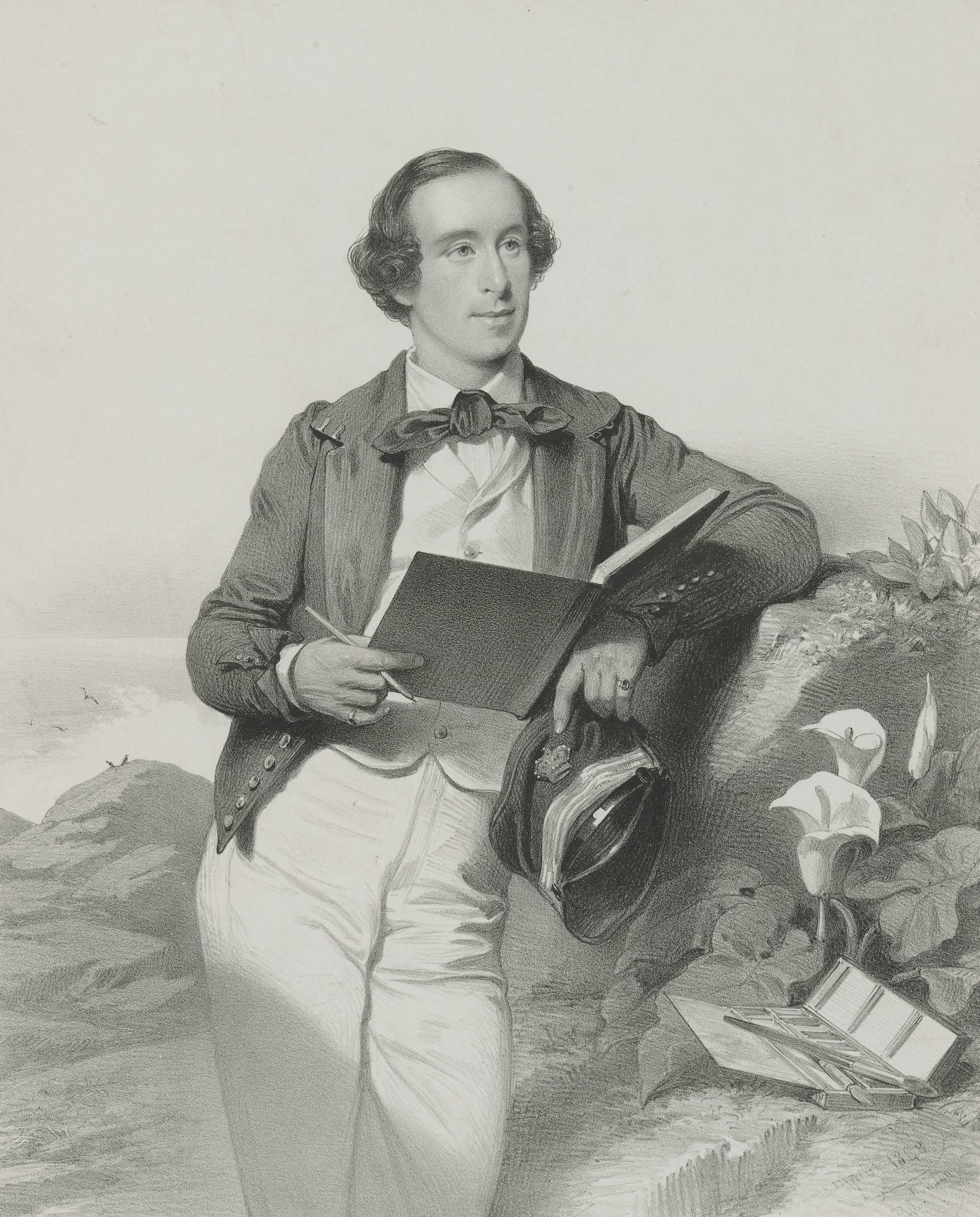

The palest, smoothest and most tranquil portrait pair comprises the matching wax medallions depicting Sir George Grey and his wife Eliza – the latter familiar to Friends of the National Portrait Gallery as the Friends’ elegant logo. Yet the milky surface of Theresa Walker’s representations of the Greys is at odds with the mess of their life, together and apart, over some fifty-seven turbulent years. Sir George Grey (1812-1889) was born in Lisbon the week after his soldier father was killed at Badajoz. Schooled in England, he attended the Royal Military College at Sandhurst and served in Ireland before forming the intention of seeking a site for settlement in north-western Australia. Travelling as far as Cape Town in the Beagle, he arrived with his party on the schooner Lynher at Hanover Bay in early 1838. Only a few weeks into his first journey of exploration, Grey was speared in a ‘collision with the natives’ and became critically ill. He rallied enough to be lifted onto one of the half-wild ponies they had brought from Timor, and went on to discover and name the Glenelg River. After some months’ recuperation in Mauritius, he returned to Perth – a town not then ten years old – looking for more adventure. More calamitous than his first journey, his proposed exploration of the coast to the north culminated in a 300-mile march after his party’s boats were wrecked. In August 1839, recently made a captain, he was appointed resident magistrate in Albany. Here he met Eliza Lucy Spencer (c.1819-1898), daughter of the incumbent, Sir Richard Spencer. He cultivated her acquaintance as he finalised his Vocabulary of the Dialects Spoken by the Aboriginal Races of South-Western Australia (1839) and they married in November. The following year they returned to England, and in Brighton he finished the two-volume journal of his expeditions of discovery, which was published in 1841. All his life Grey was an avid naturalist, collecting specimens of plants and rocks wherever he found himself, and as well as writing extensively on native languages and customs he was a fervent collector of books.

When he was offered the Governorship of the near-bankrupt colony of South Australia, Grey resigned from the army and returned to Adelaide, in which he and his bride had previously enjoyed the hospitality of Governor Gawler. In late 1840, on the journey back, Eliza gave birth to a son, but in Adelaide five months later the baby died. He had apparently been neglected, and Grey blamed his wife for his death. Although the evidence is oblique, it seems Eliza was never reconciled to life in Adelaide, which, although a well-planned town, had only been founded four or five years before she and Grey arrived there. Grey was popularly resented for his drastic economic measures – the necessity for which he slated home to Gawler – and for his obstruction of representative government. At one stage of his leadership, according to Manning Clark, one in seven men in Adelaide was on unemployment relief ‘under conditions, [Grey] was pleased to say, from which he had deliberately removed all “ease and enjoyment”’. The couple lived relatively secluded lives at the small, brand-new Government House, the grounds of which were twice invaded by angry demonstrators during their time there.

They entertained rarely, partly because Grey was determined to emphasise Gawler’s excesses through his own frugality. As Governor of this new colony – and subsequently of others, in New Zealand and South Africa – Grey, like so many other colonial leaders, juggled an incredible range of rights, responsibilities and interests. Over five years in Adelaide, through a succession of cost-cutting measures both large and absurdly small, he nearly managed to balance the colony’s budget. The inscription on this medallion refers to the abolition of harbour rates and port dues, which opened South Australia in 1845 to the ships of all nations. Although his policy toward the indigenous people of the region was uncompromisingly (and futilely) assimilative, his appointment of explorer Edward Eyre as Protector of Aborigines at Moorundie stabilised the relationship between original and new inhabitants and opened the area up to grazing settlement. As a result of this appointment, Eyre wrote the Account of the Manners and Customs of the Aborigines and the State of their Relations with Europeans, published in 1845. Grey took George French Angas with him when he was trying to make contact with Aboriginal people in the south-east, resulting in Angas’s South Australia Illustrated (1847), a copy of which is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

In 1845 the Greys left Adelaide in pressured circumstances, following dispute over the payment of a government debt. Arriving as the new Governor of New Zealand as the first wave of land wars between Maori and English settlers was in full swell, Grey faced a fresh set of challenges, to which he responded autocratically. Although he was able to achieve a crude settlement between some indigenous leaders and settlers, and trade began to pick up over the years he was in charge, again he deferred the development of representative government in the colony and could not win the respect of his colleagues.

Apart from accompanying Grey from time to time on his official duties, Eliza stayed at home at Government House, where some of those with whom she came into contact described her as ‘a perfect devil’, ill natured, untrustworthy, and given to tantrums. She was credited with ‘beautiful black hair, and still better brown eyes, and a very good forehead and complexion’, but her mouth is said to have twisted about ‘in a rather ugly way’ as she would recline on the sofa and engage in light conversation, it seems, alas, often talking satirically of many of her contemporaries. In this period one display of affection at least between Mrs Grey and her husband was noted – when his knighthood was conferred in 1848 and she gave his hand a squeeze.

During Grey’s governorship of New Zealand his lieutenant governor was Edward Eyre, who had arrived in 1846 with the promise of an £800 salary and a £400 living allowance. Before he even arrived, Grey had cut his living allowance to a ‘forage allowance’. As the years passed, according to the New Zealand historian W. Gisbourne, Grey’s attitude to Eyre was characterised by ‘publicly making little of him … worrying him officially and … aggravating each anomaly of his position until it became absurd and intolerable’. When Eyre’s pretty fiancée, Fanny Ormond, arrived in New Zealand to marry him, she strayed into Eliza Grey’s path before the two could meet. Mrs Grey detained Fanny, persuading her to stay with her until Eyre came to collect her. By the time he arrived she had so poisoned Fanny against Eyre that she spurned him, telling him she would return directly to England. So indomitable in exploration, but so awkward in address, Eyre was desolate, ‘determined to shut himself up in his house and lead the life of a hermit’, but his friend Bishop Selwyn intervened on his behalf, bad weather hindered Fanny’s schedule, and the wedding took place. Grey gave Fanny away, ‘perhaps as a gesture of apology for his wife, who had in effect kidnapped [the] bride’ according to Eyre’s biographer Geoffrey Dutton.

While he retained his official title, and the sympathy of the Colonial Office, Eyre spent the last two years of his appointment effectively unemployed, stripped by Grey of all powers and responsibilities. By the time the Eyres left New Zealand, the Greys had forced them and their children to move out of their home, Government House in Wellington, and to rent premises at their own expense while the Greys stayed, to no particular end, in the official lodgings. As the Greys left Auckland at the end of 1853, by which time he had earned the animosity and suspicion of his local colleagues and the enlarged respect of the British Government, he announced that his wife had ‘cheered me and sustained me’ and ‘shared, as far as was in her power, in my trials’.

After a spell in England the Greys relocated to Cape Town, South Africa, where Grey was to serve as governor of Cape Colony and high commissioner of South Africa. They arrived just after slavery ended and an embryonic Legislative Council had formed, but the city was slum ridden and relations were uneasy between settlers of Dutch origin, the minority group of English heritage, and the indigenous population. Here, according to the account in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, it did not take Grey long to raise the hackles of his Legislative Council, the colonists and the indigenous inhabitants as well as the War Office, the Treasury and the Colonial Office. In response to mounting pressure in the colony and censure from England, Grey came close to collapse - but it was Eliza who succumbed to nervous breakdown. She returned to England towards the end of 1858 to undergo medical treatment. Grey followed in 1859. As they returned to Africa in 1860, she committed an indiscretion involving a flirtatious letter. The ship’s doctor swore that Grey would either kill his wife or himself unless she was put off the vessel at Rio de Janeiro. She was - and the pair was separated for the next 37 years.

Although it was to Cape Town that Grey proceeded alone, he was to return to New Zealand for his second term as governor a few months later. Injured from the outset by the vicissitudes of his career and personal life, he became increasingly erratic in his professional decisions as war intensified between Maoris and white settlers with the ‘invasion of the Waikato’ in 1863. After a series of disasters, quarrels and highhanded breaches of office he was dismissed for defying his orders – which he seems to have regarded as mere suggestions - in 1868. He was to spend most of the rest of his life as a member of the New Zealand House of Representatives, in which capacity he did not fail to alienate and offend his colleagues but nonetheless gained some useful ground, such as the abolition of plural voting.

In 1896 Lady Grey sought a reconciliation, which, when effected, was romanticised by the press; it was even fancifully claimed that Queen Victoria had intervened in the Greys’ relationship. Once the couple was reunited, however, Lady Grey lost no time in entering into financial negotiations. Grey became suspicious, and according to his biographer, J. Rutherford, ‘the excitement made them both ill’. Grey’s resources were less than Eliza, perhaps, had expected, and they could only afford to live in a ‘rather cramped suite of rooms’ in South Kensington where she proved ‘overbearing’. Early the following year, it was arranged for Lady Grey to go to Bournemouth, again, according to Rutherford to ‘relieve [Grey] of the excitement of her presence’. Grey lost his mind, and when she died in September 1898 he could not comprehend it. He died himself a few weeks later, and was buried in state at St Paul’s Cathedral.