As the Adelaide Festival took root and the Opera House took shape, the stage was set for glittering artistic combinations.

Patrick White read the journal of Edward Eyre in London during the Blitz in 1940, and as he read, it seems, the idea of writing a novel about an explorer germinated.

The previous year, in Sydney, the young painter Sidney Nolan had made his first ballet décor, for the Ballets Russes' production of Icare. A couple of years later, in London, South Australian-born Robert Helpmann created his first ballet, Comus, for the Vic-Wells (later Sadler’s Wells) ballet. A few years after that, 16-year-old Peter Sculthorpe began studying composition at the University of Melbourne. In the early 1960s, by which time Nolan and Helpmann had been based overseas for many years, the four men came together in various combinations in an extraordinary season of cultural optimism, collaboration and rupture.

After the war, Nolan hitchhiked to Queensland, where he visited Fraser Island and began his great series of paintings on the theme of Eliza Fraser. By the turn of the decade he had also completed his Kelly series and a number of paintings of the Queensland desert. Patrick White saw Nolan’s works depicting the outback at Sydney’s David Jones Gallery in 1949 and 1950. According to the account in David Marr’s superb biography of White, the author felt that Nolan was coming at the same material as he was himself in the mighty novel – now based loosely on Leichhardt, not Eyre – that was beginning to form in his mind.

White’s Voss was long in coming. He began to put it down in the summer of 1954-5. Although he had not met Nolan, he had followed his career, and he asked him to do the jacket for the Eyre and Spottiswoode edition of the book, which was published in 1957. White loved Nolan’s preliminary sketch of a ‘thin and prickly’ Voss, sent to him on a postcard. On the finished cover, he thought his tortured protagonist looked like a ‘fat amiable botanist’, but such was his respect for Nolan’s art that he went along with it nonetheless. Nolan did a second cover, for an edition of The Aunt’s Story, before the two men came face to face.

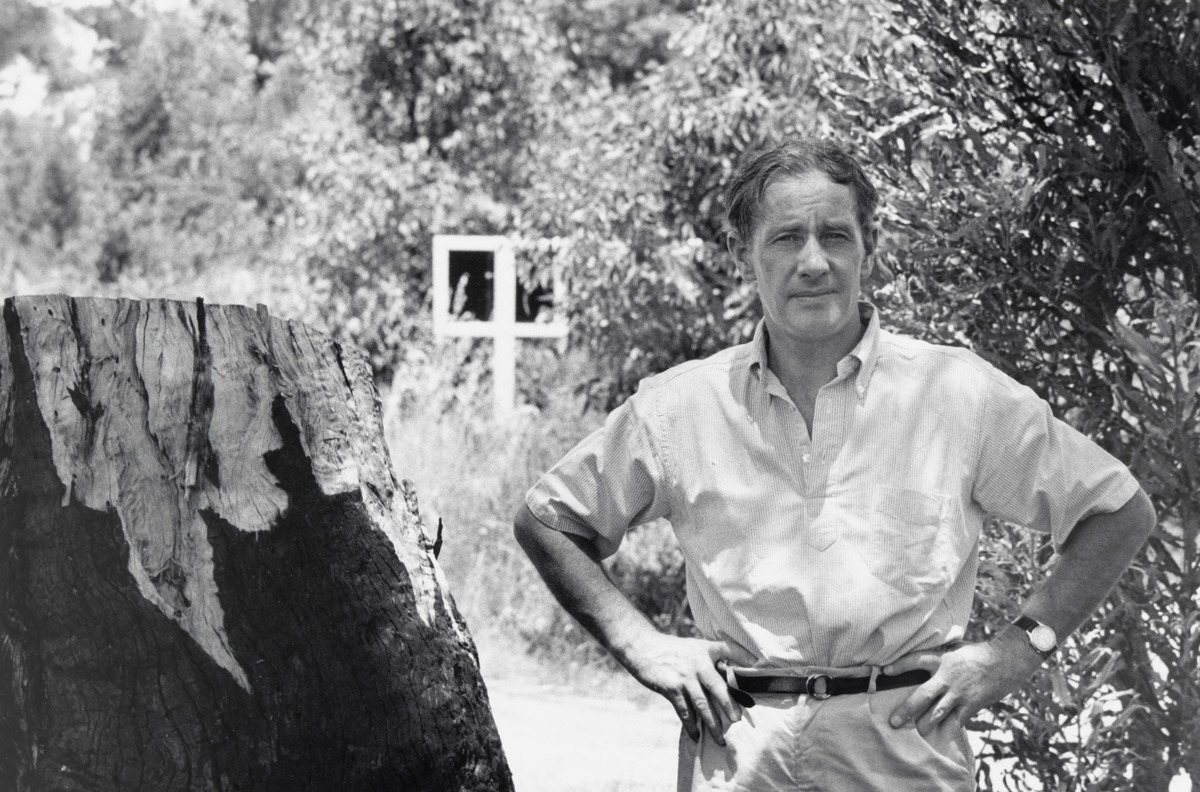

When White and Nolan met in Florida in 1958, White found they ‘had so much to say, as often happens when we meet those who have been saved up for us.’ He found Nolan to be a man remarkably ‘so much himself’, and noted his eyes, ‘of a blue that I can imagine might suck the unwary right under’. Although the two men were excited and stimulated by each other, Nolan was not an assiduous correspondent and it was his wife, Cynthia, who nourished his relationship with the author. White was charmed by them both; they became one of his favourite couples, along with the South Australian poet, historian and man of letters Geoffrey Dutton and his elegant wife, Nin, who came into White’s life at the beginning of the 1960s.

In London in 1961 Nolan and Cynthia read Riders in the Chariot before White’s English publisher had finished it. White was keen for Nolan to do a cover for the book, but the artist was stretched by other projects. With time running out, White’s publisher Maurice Temple Smith came across a series of works that he believed Nolan could only have painted in response to the book. The work he selected from these turned out to be the most successful of the artist’s jackets for White; the book itself was White’s biggest critical and commercial success to date. The author, who was a significant collector of art, wrote to a friend that Nolan had sent him the original of the Riders jacket ‘so my collection of Nolans is growing without my ever having bought one! This painting is so much subtler and to the point when you actually see it; one would say it had actually been designed for the book, which in fact was not the case. I do hope the Nolans will come back here. His painting gives me such a lot in my work, and he claims I do the same for him…’ The same year, Nolan did the cover for a paperback edition of The Tree of Man.

The first Adelaide Arts Festival was staged in 1960. The following year, Geoffrey Dutton, who was on the Drama Committee, suggested White’s unperformed play The Ham Funeral for the 1962 Festival. His proposal was roundly rejected by the festival’s governors, and the play premiered as a production of the University Guild at the University of Adelaide in late 1961 instead. Although White’s play A Season at Sarsaparilla had gleaned sensationally negative headlines in the popular press in Sydney and Melbourne, it was staged to great acclaim in Adelaide in September 1962 and the following year, it seemed probable that Night on Bald Mountain would be staged at the Adelaide Festival of 1964. However, it was rejected, much as The Ham Funeral had been, by the governors. ‘All very ridiculous’, White wrote, but I do not like the idea of playing the part of the intellectual and social pariah of Adelaide [again].’ While clambering over the unfinished Opera House with Jørn Utzon in March 1963 White felt uncharacteristic hope for Australian culture. Stefan Haag, director of the Elizabethan Theatre Trust, put it to him that he might write the libretto for an opera to open the Opera House. White instantly thought of Mrs Fraser, imagining himself at the opening night of the ‘Britten – Nolan – White opera’. As the debate over the staging of Night on Bald Mountain raged in Adelaide, he was having a high time in London with the Nolans, who introduced him to Benjamin Britten in about September 1963. The meeting was awkward and Britten dropped out of White’s plans for the opera. Instead, he agreed that Peter Sculthorpe – the ‘first Australian composer whose music I have found in any way exciting’– should have a go at it. White and Sculthorpe met at White’s home in late 1963; the relationship got off to a bad start when White, always an anxious and sensitive cook, made the vegetarian a lunch of chicken. As the meal progressed it emerged that Sculthorpe had been thinking of composing a song cycle, and as it happened, White had already written the words of one – ‘Six Urban Songs’. White gave the words to Sculthorpe in the hope that they might ‘help us to approach the opera’. But from the outset the two envisaged different kinds of singers and instruments, and when the composer received White’s start on the opera libretto in March 1964 he was ‘dismayed’. It seemed, as White later admitted to a friend, that ‘we got together too late, and by that time the idea had set too rigidly in my mind [for me] to be able to alter it to satisfy a collaborator’. By April 1964, according to Marr, the opera was ‘dying within him’. Later that year, at the Aldeburgh festival in Suffolk, Sidney Nolan CBE showed a series of paintings – the first of a number of such he produced – inspired by Britten’s music.

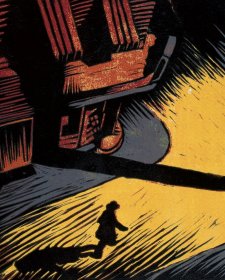

Robert Helpmann grew up in the mining town of Mount Gambier, where he learned to dance on pointes because his teacher had never had a male pupil. In the early 1930s his parents took him to Melbourne, where he so impressed the touring Anna Pavlova that she took him on with her company. Based in London from 1932 onward, he reached the apogee of his international fame touring the USA at the end of the 1940s, starring with Margot Fonteyn in the Royal Ballet production of Sleeping Beauty. In 1955 he visited Australia, observing ‘an outstanding change since I was last here … you have a flourishing ballet company, the Borovansky; the Elizabethan theatre trust, ballet groups and symphony orchestras in every state. This is a thrilling advance since, in the long run, every country is largely judged by what it produces in art form.’ His stay here coincided with a tour by his friend Katherine Hepburn. The two went camping for some nights in the Dandenongs, where they were entranced by the sight of lyrebirds dancing. At the beginning of the 1960s, Helpmann signalled his interest in choreographing a work for the Adelaide Festival. His offer accepted, he began work on The Display, which combined elements of his childhood experience of male hostility with what he had seen in the forest. Although his involvement is recorded by neither his own biographer, nor Helpmann’s, Patrick White is said to have been asked to provide a scenario for the ballet, but when the draft arrived Helpmann is said to have hated it. In the end, Helpmann devised both scenario and choreography, while Malcolm Williamson supplied the score and Sidney Nolan did the décor. The Display depicts a bush picnic, where alcohol and football lead to violence; a girl, left alone after a threatened rape, ends the day in the embrace of the lyrebird. Australian rules star Ron Barassi was called in to advise on the football scenes. It was all – according to dance authority Michelle Potter – ‘ostentatiously Australian’.

Fresh from making the décor for the Royal Ballet Production The Rite of Spring in London and New York, Nolan took a completely different approach to the Australian work, using a series of gauze panels to evoke the filtered light of the lyrebird’s habitat. According to Potter, the designs were particularly successful. A contemporary reviewer remarked on Nolan’s creation of ‘the deep, rich mysterious gloom of a sunlight shafted Australian rainforest with the pillars of its ghostly white gums rising through its depths’. On the opening night of The Display, which was dedicated to Katherine Hepburn, there were 20 curtain calls and a 15-minute ovation. Five and a half thousand people attended its four performances at the Adelaide Festival of 1964. Over the ensuing years the Australian Ballet performed The Display regularly, both in Australia and overseas.

Whatever he may have made of The Display, White had other things on his mind that March. In a compromise between the Play Committee and the Adelaide Festival governors, Night on Bald Mountain was mounted as a Fringe event, and was well attended. Nolan was showing paintings of Africa, and White found the opening at the Bonython Galleries the most ‘gruelling’ event of the Festival week. Once he returned to New South Wales, according to David Marr, all the differences between him and Sculthorpe were exposed. Sculthorpe was willing to press on, but White refused to, and asked the young composer to return the ‘Six Urban Songs’ so that he could destroy them.

The following year Sculthorpe took up a Harkness Fellowship to Yale. A proposed project involving Helpmann, Sculthorpe and his friend Russell Drysdale – whose retrospective show was mounted at Adelaide’s John Martin’s department store during the 1964 Festival – did not get very far, because of Helpmann’s misgivings about the other men’s theatrical experience. In 1968, however, Sun Music, with music by Sculthorpe, choreography by Helpmann and décor by Kenneth Rowell was premiered by the Australian Ballet. Sculthorpe and Drysdale each created works inspired by the other’s. The composer has said that Nolan’s painting influenced him only in that it supplied him with a precedent to create musical works, such as Irkanda, Sun Music and Kakadu Songlines, in series. Other writers, however, have suggested that Sculthorpe’s Eliza Fraser Sings (1978), a music-theatre piece with words by Barbara Blackman, and two orchestral works, Mangrove (1979) and Great Sandy Island(1998) emerged from both Nolan’s Fraser island paintings and his own aborted collaboration with White.

Helpmann became co-director of the Australian Ballet in 1965, when he is reported to have stated that he did not despair about the cultural scene in Australia ‘because there isn’t one here to despair about.’ In 1966 he was Australian of the Year, and he was knighted in 1968. Co-director of the Australian Ballet until 1974, and its sole director in 1975, he was Artistic Director of the Adelaide Festival in 1970.

Over the course of the 1970s White wrote no plays. During this period, in 1973, it fell to him to serve as Australian of the Year – an office that both touched and embarrassed him. He once said that Australia ‘is in my blood – my fate – which is why I have to put up with the hateful place … A Londoner is what I think I am at heart but my blood is Australian and that’s what gets me going.’ He envied the Nolans’ capacity to ‘fly in to be renewed, but get out before they are chewed up.’ For him, Nolan’s 1967 retrospective at the AGNSW was ‘the greatest event – not just in painting – in Australia in my lifetime.

It has made up for a lot if not all the bitterness for having been dug out of this pit.’ When he won the Nobel Prize in 1973 he asked Nolan to accept it on his behalf, sensing that the artist would enjoy the pomp of the occasion as much as he himself would be discomfited by it. In 1981 Nolan was knighted, and ten years after the Nobel ceremony he was to accept his own exceptional honour, the Order of Merit from HM Queen Elizabeth II. By that time, however, his friendship with White was long over.

After mulling over the Eliza Fraser story for decades, White wrote A Fringe of Leaves in the mid-1970s. Nolan’s biographer Tom Rosenthal believes that throughout the novel there are images which ‘surely spring in part from Nolan’s paintings’. But as Marr observes, the creative relationship that began with Mrs Fraser ended with her. A Fringe of Leaves, bearing a Nolan painting on its jacket, was published in 1976. After Cynthia Nolan – ‘this king-fisher of the spirit’, as White called her – took her own life in November that year, the correspondence between White and Nolan ceased. When it was time to find someone for the jacket of The Twyborn Affair, White told his publisher that he and Nolan were no longer in touch. However, Nolan did not comprehend the change in their relationship until White’s autobiography, Flaws in the Glass, appeared in late 1981. It contained a scurrilous depiction of the painter. Advised against legal action, Nolan responded with horrible paintings depicting White and his gentle lifelong partner, Manoly Lascaris. Geoffrey Dutton defended Nolan after Flaws in the Glass appeared; White’s bond with the Duttons, too, was extirpated. When Jim Sharman was announced as the new Director of the Adelaide Festival in 1981, White immediately started work on a new play, Signal Driver. The play opened the 1982 Festival, which also featured a performance of a fragment of the forthcoming opera of Voss. David Marr recalls that White was ‘everywhere in Adelaide’ at that time, as ‘the warmth of Signal Driver’s reception …seemed to consign the old humiliations to history.’ Netherwood premiered in Adelaide in 1983, and the opera Voss – rocky territory for White, partly because Nolan owned the film rights to the work – premiered at the Festival of March 1986.

Sir Robert Helpmann CBE died in September that year in Sydney. Though he had once told a journalist ‘I’m a good hater … I’ll bury him’, Nolan made reconciliatory advances to White in August 1990, but the author scorned the idea and spurned him until his death a few weeks later. Sir Sidney Nolan AM AC CBE died in 1992, the second Australian (after Christina Stead) to become an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Australian National Living Treasure Peter Sculthorpe AO OBE, who believes that this country is ‘probably the last place in the world where a composer can honestly write joyous music’, became the fourth (following AD Hope) in 2002.