On first seeing her portrait by Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein is supposed to have complained, “I don’t look at all like that,” with Picasso replying, “You will, Gertrude, you will.”

In his Portrait of Gertrude Stein, Picasso captured certain of Stein’s identifying traits, her solidity to be sure, but also her inner strength, her ambition and daring, with out being a ‘faithful’ or photographic likeness. And indeed, as Picasso predicted, posterity has determined that the Gertrude Stein we recognise is in the image that he painted in 1906. The anecdote illustrates one of the prime debates at the heart of portraiture – the importance of likeness and its links with essential meaning. The question of likeness is central to portraiture, but the term itself is somewhat equivocal. The cliché suggests that a portrait that is a ‘true’ likeness will reveal the sitter’s soul. While this may be an unrealisable ambition, a good portrait will offer, at the very least, some insight into the subject’s personality and capture something of the attitude, unique mannerisms or any of the other features or traits that form the individual nature of the person. In short, the portrait must convey something about the subject. Truth in portraiture entails more than the depiction of the physical resemblance of an individual, ultimately implying a mix of associations between appearance and character. Since the late 20th century the portrait has come to terms with the complexity of identity and assumes that a literal or superficial likeness is inadequate in representing the multiple aspects of an individual personality. Truth and Likeness is an investigation of the importance of likeness to portraiture. The exhibition considers the essential dilemma in portrait making – how to record the visible outer surface and provide an insight into the character of the sitter – and asks if truth in portraiture exclusively implies a mimetic approach. Truth and Likeness contrasts portraits by eight painters who are working with varying degrees of realism.

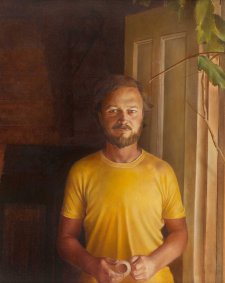

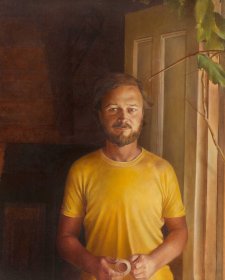

Artists Josonia Palaitis, Jiawei Shen, Jude Rae and Cherry Hood work within the realist tradition. Josonia Palitis paints her subjects and their environment with an astonishingly high degree of surface detail that evokes the physicality of the sitter and their background, creating a weight of conviction that they actually exist. Jiawei Shen’s subjects are just as realistic but he increasingly adds symbolic attributes to his paintings to inform the viewer of the subject’s identity. Jude Rae provides no clues to the background of her subjects in terms of dress or belongings, offering only the unadorned visage, eyes closed and all the more intimate for being so open to scrutiny. Hood’s young sitters, in contrast, stare directly at the viewer to initiate a psychologically disturbing confrontation. The soft vulnerability of their tender faces is startlingly real yet exposed as fiction by the dribbles of watercolour paint. Post Freud, it is inevitable that artists attempt a psychological portrait that is intended to reveal the vital inner core of personality and not just the public surfaces. Ben Quilty, Mike Parr, John R Walker and Patrick Pound, unlike the first group of artists, work from an expressionistic base and balance representation with concern for the tactile and expressive qualities of paint.

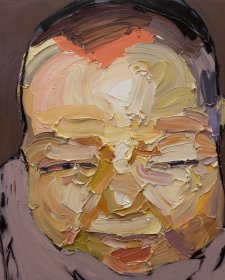

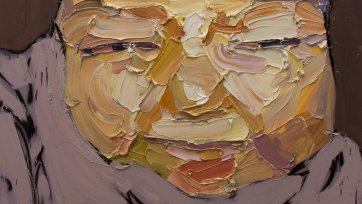

Quilty lays down meaty abstract slabs of paint, yet the individuality of his sitters, be they a friend or his infant son, emerges through characteristic pose or recognisable gesture. Walker jabs at the canvas, working as quickly as possible to capture the sensation and impact of the initial impression. Parr’s agitated lines describe his inner feelings, mood and temperament as much as the familiar features of his own face. Pound, in contrast, reduces the familiar visages of his friends to schematics, simple silhouettes that question just how much (or little) information is required to identify an individual, to create a viable likeness?

The sculptures of Sam Jinks and Adrienne Doig extend this opposition into the third dimension. Jinks records the features of his son in obsessive detail to conjure up the disquieting hyper reality of a waxwork while Doig’s conceptual self portrait was paradoxically produced by 12 doll makers who have never seen her. All of the works in the display offer likeness in differing ways but the exhibition effectively contrasts objective and subjective styles of portraiture. The objective image provides a dispassionate and detailed recording of surfaces, but can appear cold and empty. The subjective image reveals inner feelings but risks loss of recognition. This dichotomy lines up with many of the debates of recent art history, particularly the value placed on either craft (ie technique) or innovation. Equally relevant is the split between rational and emotional responses that might be evoked.

Given the predetermined objectivity of the camera, the work of four photographers – Petrina Hicks, Darren Siwes, Warwick Clarke and Sue Ford – is also included in the exhibition to act as a foil to the painters. Their work will both reinforce and undermine this assumed neutrality of the recording process. In her photographs of Lauren, Hicks subverts the supposed objectivity of the camera both with the improvements she made after the shoot with computer aided enhancements and with the invitation to choose the ‘best’ likeness from the group of three. Siwes moves from the idea of likeness in his self portraits to the idea of identity. Siwes’s indigenousness is the subject of the photographs and his only just visible likeness shows that is not what the camera records that is important but what the viewer sees or chooses to see. Clarke’s photographs, by bringing together couples who look like each other, questions the validity of mimetic likeness as the prime means of identifying a sitter. Ford, finally, explodes the myth of likeness as a true record of an individual. With a sympathetic nod to the fictional Picture of Dorian Gray (which aged as the subject of the painting remained young) Ford’s multipanelled portraits taken at regular intervals record the tracks of time on an ever changing likeness.

Likeness is, at best, fugitive and impermanent. It seems paradoxical that even a photograph can elicit the notion that ‘it doesn’t look like me’. The camera is clearly not objective as might be thought or alternatively likeness is only component of the ‘true’ portrait. Looking at a portrait, the viewer wants to know what a particular person looked like but also understand what kind of person they are looking at. Michaelangelo, criticised for the idealising the Medici portraits in Sagrestia Nuova beyond mere likenesses, replied that ‘what would it matter in a thousand years time what these men looked like?’ For Michaelangelo, the achievement of his subjects and his own achievement in creating the portraits was what counted and constituted a greater truth.