It’s amazing that anyone managed to keep a pet going before the invention of the internet. Online these days, on a plethora of owners’ forums, you can read all about the care of, say, Mexican neotenic salamanders, but in the early 1980s Nicholas Harding had to learn the ways of axolotls first-hand, by courtesy of a series of horrors involving his own – Montezuma – and his tankies. Now, practically everyone knows that by zipping their gill slits, leaping upwards and opening their jaws all at once, axolotls generate a vacuum; but empirically, Nicholas could only be sure they offed his catfish, Spike, sucking his eyes out and leaving his corpse floating on its side. The crunch came when he came home one night to catch Monte red-handed, half of Spike’s last surviving mate hanging out of his slash of a mouth. He tried separating them in a pioneering procedure, but lost them both – speaking euphemistically, not literally – on the table.

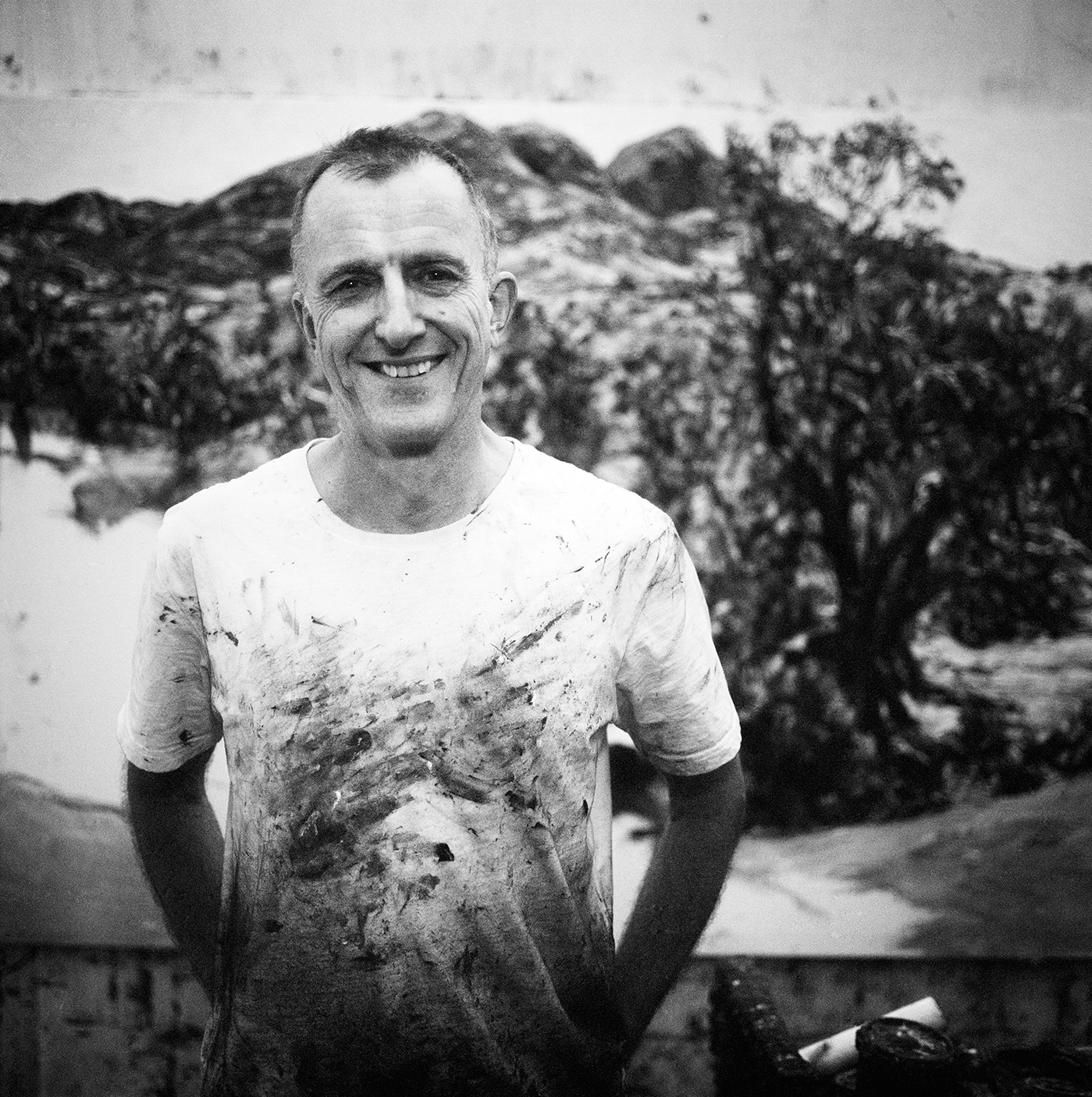

Nicholas Harding came here from England with his family in 1965, just before he turned nine. They came from a place where the landscape was benign; his grandparents grew prized flowers, and they used to picnic in the velvety grounds of grand houses. A few days after they got to Sydney, Harding took off his shoes to run across a grassy slope and was introduced, rudely, to bindies. His family had often gone to the beach around Eastbourne, where at low tide it was a long walk out, hanky on head, for a paddle. In Australia the beach was blinding; you’d get burnt and maybe bitten by sandflies, and you could well drown, like the prime minister. Rambling over English parks and commons, little blue-eyed Nicholas introduced an exploratory twig into any hole he found. Here, he was warned, you could get killed doing that.

As it happened, the Hardings settled in funnel-web central: Normanhurst, thirty-two kilometres north of the Sydney CBD on the edge of wilderness. A black snake often lay on the warm driveway, and Mrs Harding wanted it gone, but whenever she spotted it and called to her husband, he ran and got the camera, so he could send pictures back to the Old Country. There came a day when she and the reptile came face to face as she was heading out, fully dolled-up for lunch. Nicholas saw her hotfoot it in high heels to grab the shovel, come back and chop it into cutlets, which is a tale for the psychiatrist if ever there was one. Over the years the youngster got his hands on various mice and guinea pigs, but they served mainly to illustrate the concept of mortality. Eventually, a starving, tufty cat staggered out of the bush into the Hardings’ garden. Nicholas led his siblings in a nagging campaign until their parents said they could keep him. It was his first regular pet; apart from the axolotls, he hasn’t had another one.