Headlam periodically becomes bored with one art medium and turns for relief to another. She’s invigorated by watercolour, which calls for a bold approach, yet a light touch. You can’t fiddle with it; one go at it, and the work is either made, or ready to throw away. You drop paint on; you move it around a bit, dab it a little, leave it to dry – but when you come back, it will have moved again of its own accord. Her wombat may be a miracle materialising from the combination of skill and the caprice of the watercolour. But what luck, to get the plane of the face, the solidity of shoulder and haunch; and what skill, to get the gleam in the animal’s tiny left eye! Years after her famous bedchamber painting, Headlam made an affecting watercolour of Pamphlet after she’d been treated for a haematoma of the ear. She’s isolated on the white paper, her subdued little form emphasised by the sad puddle of shadow, her disconsolate face framed by a protective contraption that vets call an ‘Elizabethan collar.’ Headlam was enchanted by the term.

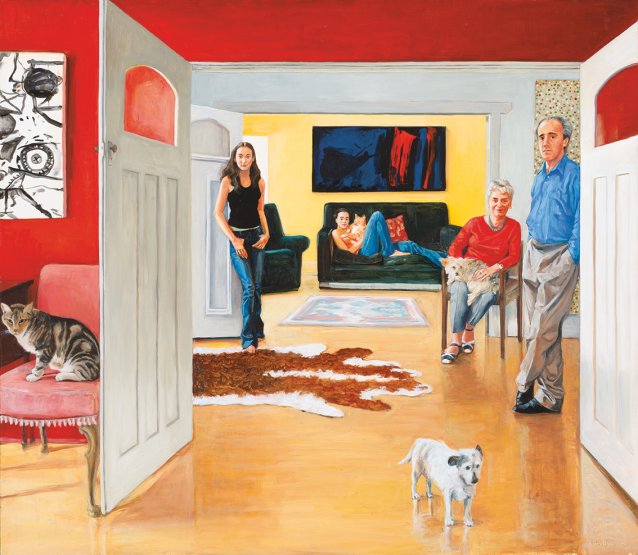

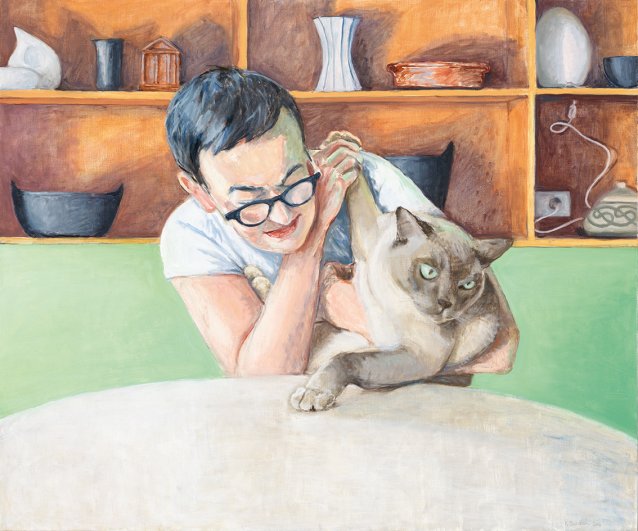

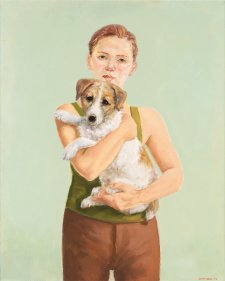

Between 2005 and 2007, Headlam made three major portraits on commission: two were set in the homes of her friends Charles Nodrum and Hermina Burns, respectively, and one in her own house. Nodrum, who’s Headlam’s courtly English-born gallerist (the new term for what used to be called an artist’s ‘dealer’), likes to refer to the dramatis personae in his commissioned family portrait. Indeed, Headlam’s constructed the picture to resemble a theatre set, its props confined to a few pieces of furniture and a mere fraction of the pictures that Charles’s amassed over his many years in the art game. The ‘actors’, though, seem transfixed by the painter, herself; they’re all looking at her (or us, if you like) very keenly. Though he has an air of casual command (and the ‘swagger portrait’ has a long history in Western art), Nodrum’s expression is diffident compared to those of the three women in his household. The elder daughter, Anna, her stance a feminised form of her father’s, projects her beauty challengingly at the older woman painter. She’s near the door; but at the same time, her toes dig in and grip the hide of the rug. We infer that while, for the most part, she’s ready to leave, she adheres to the comfort and familiarity of the household. Kate, the younger daughter, is a long way in the background, clutching her cat Honey in her arms. We read her position as Headlam’s indication that in life, Kate is yet to come forward.

In keeping with the stilted nature of the picture, the huge cat on the pink chair looks rather stylised – that is, not very real (although that said, there is a type of domestic cat that has just those sorts of stripes, called, excruciatingly, a toyger). Nodrum recalls that Max really was a cat of gargantuan size, writing that ‘he patrolled his territory with the watchful eye and rhythmic stride of the best of his kind’. Mrs Nodrum is the picture of agreeableness; she calls to mind Jacques-Louis David’s Comtesse Daru, one of the most beguilingly complacent figures in European art history. She has her hands full with Tiny, who was perpetually quivering with nerves; like all the other family members, he’s looking intently at the artist. Clearly, the one in the foreground is the senior dog; whatever else it may be, the family portrait is evidently a tribute to Emma, once tirelessly playful, now a stiff-jointed, vacant little animal, her tail down, her coat thinning, who looks fixedly at nothing.