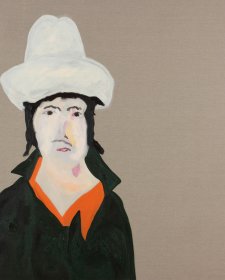

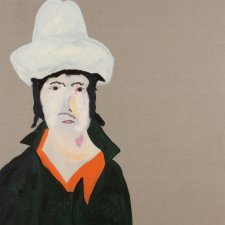

It’s a fun fact that when Darren McDonald was painting the jaunty double portrait of his partner, Robin Astley, and her cat George, the first paint strokes that he laid down were the white lines of the cat’s whiskers. The rest of the cat, he painted around them, taking care not to mix the wet white and black. Most painters wouldn’t have done it this way: white paint (as opposed to say, yellow) is very opaque and can be applied effectively even over black, and the fineness of real whiskers would seem to make them ideal for overlaying. But Darren can’t wait for one layer to dry, before applying another; each one of his paintings is made in a single frenzy. As a consequence of this idiosyncratic approach, the painted George has whiskers as thick as wonky chopsticks in wildly the wrong place (not even on his face) and a head that’s much wider than an actual cat’s. As for Robin, she was never intended to be in the picture; the painter changed his mind about his composition and popped her in behind the completed form of George. This instance of indecision and revision is uncharacteristic of McDonald. Entirely typical of McDonald’s productions, however, is the intensely expressive result. While Robin is teasingly coy, demure, chaste yet a little mischievous, George, with his humanoid frown, his comparatively beady, improbably green eyes, looks rather incensed. The success of the picture – apparently against the odds, but in fact no accident – is a classic McDonald tale.

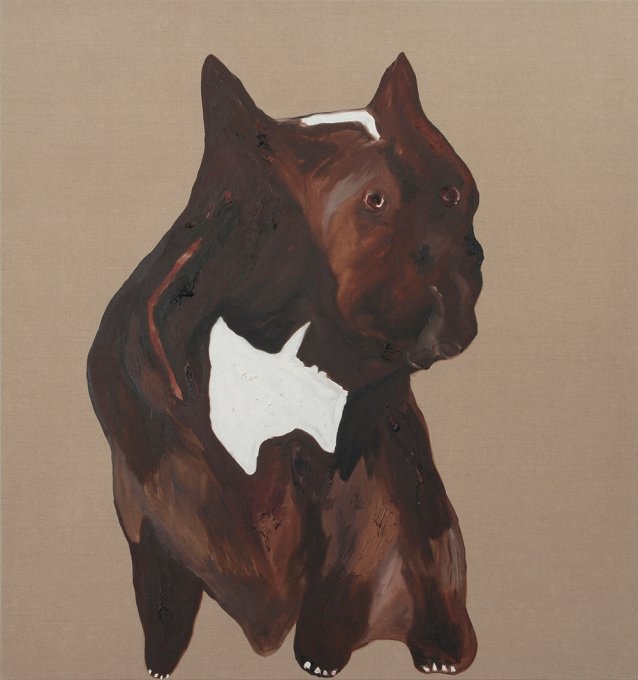

Darren McDonald lives with his mottled dog, Rupert, in the western suburbs of Melbourne, in a rented house so full of stretched, painted canvases that the two have to walk in single file on narrow paths between them. It was tough for the artist to find a rental property where he could keep his dog. Rupert negotiates the space daintily, his large ears quivering with interest. He’s had a little trouble with the law, and has to stay inside with McDonald most of the time. While their shared dispute with a neighbour’s been deeply upsetting, the artist believes that it’s brought him and Rupert closer together; he often speaks to the dog quietly, in the spirit of reassurance. He’s painted Rupert several times; though unflattering renditions, the portraits do capture his geniality (unfortunately, in a portrait he attempted of them together, the artist’s own dog came out looking more like his neighbour’s horrid mastiff). Aside from McDonald’s own works, and those of other artists with whom he’s traded, all around the house there are curios, mementoes, still life tableaux of odds and ends. On one surface there’s a jumble of defunct watches and a flintlock pistol; in a corner are two ventriloquists’ dummies; across the floor are bicycles, hats and shoes; flamboyant ties dangle from doorknobs. There are many postcards. Every surface seethes with objects, like a contemporary art installation distributed across the fittings of a working op-shop.

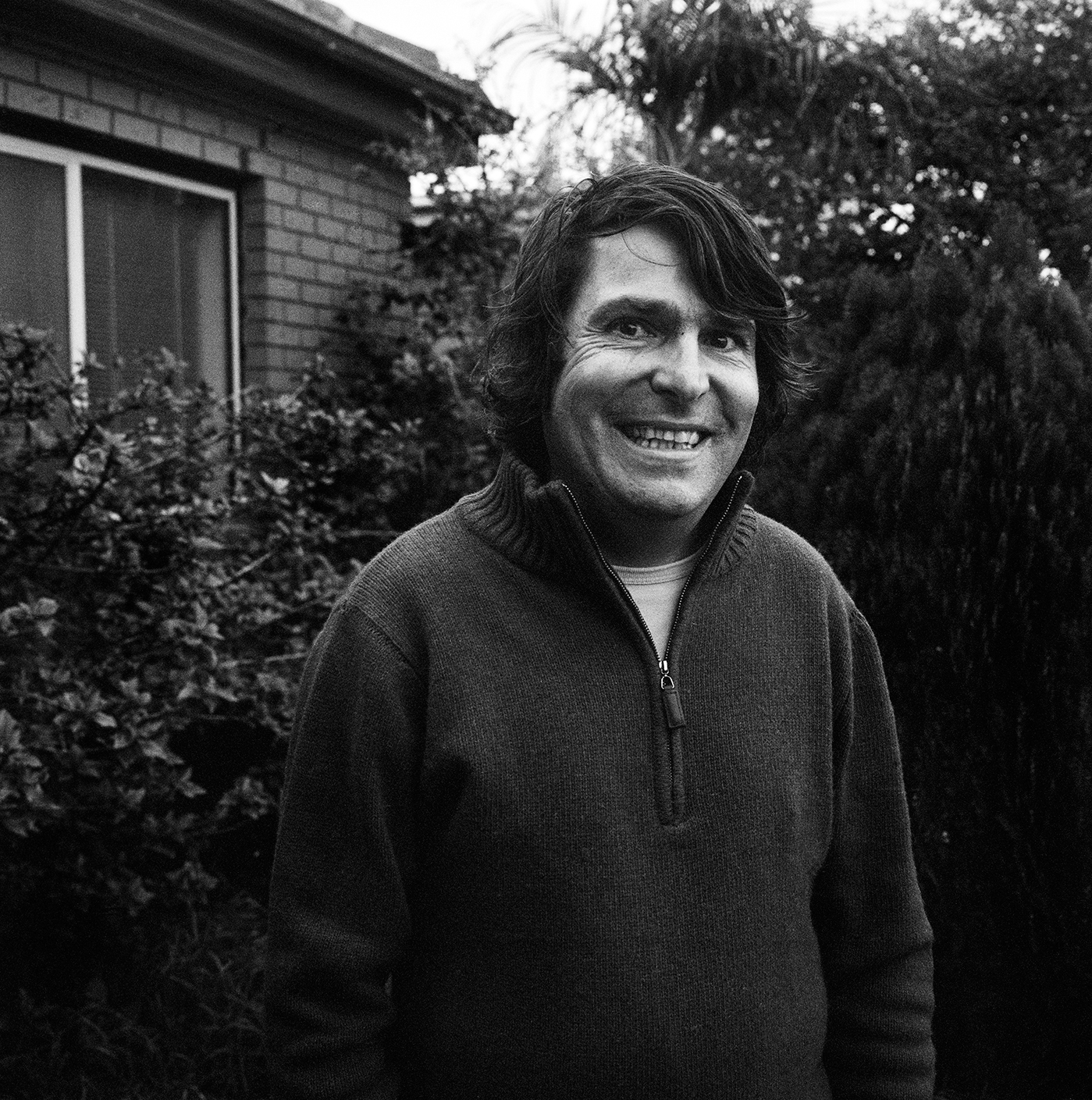

McDonald looks like a gypsy in a folktale, with olive skin, a hawk nose and very dark eyes, but he grew up in a religious home and attended a school at which the pupils were sheltered from vice and art. As he encountered aspects of the outside world, they made a deep impression on him, successively: Bat Out of Hell, the Marlboro Man, David Bowie. At one point, he trained as a chef; if he had his own cooking show, it’d be a nationwide sensation. He became enchanted with an artist and teacher who lived in Western Australia, and moved to Albany for a while; there, he started painting, too, accompanying her on excursions with her students. When they parted and he was back in Melbourne, depressed and wayward, a friend told him he had to do something with his art. He got together a small portfolio of works based on drawings he’d seen by George Grosz and Egon Schiele, and took it to an interview at the Victorian College of the Arts. His interviewers were running late, so he went to the lavatory and relaxed with a smoke. When he returned, he was the late one. One of his interviewers walked out, and the other advised him to try a TAFE course. He proceeded, accordingly, to study at RMIT.

At first, at a loss for subject matter, he copied what other students were doing. One day, an artist friend asked him if he’d ever actually been to Victoria’s Pink Lakes. Darren admitted he hadn’t, and the man - who had - shot back ‘Well stop fucken painting them then!’ He embarked on his own path with a series of cats he took from a book about Picasso. He went to Vietnam, and painted water buffaloes. From that moment on, his original vision was directed at people and animals, and injustice was one of his characteristic themes.

The wild balancing act of McDonald’s home décor (is that there as a joke? where do I actually sit down? is this ironic or what? what a lovely photo of Darren and Robin in Europe!) is reflected in his own personality. In conversation he’s disconcertingly open one minute, wry and sharp the next. Now he seems naïve, ingenuous, fragile; then, he proves himself acidly perceptive, shrewd and responsive to popular culture. At one of his exhibition openings at Melbourne’s high-end Scott Livesey Gallery, necking a beer and wearing checked trousers he was urged to purchase by a mischievous friend, he looked for all the world like an Australian SP bookie from the 1960s. Yet subjects of his paintings include Charlie’s Angels, Brian Jones and the Las Vegas magicians Siegfried and Roy with their tiger, Mantecore. It’s not surprising if the first-time viewer of McDonald’s paintings feels a bit like she’s being taken for a ride, that they’re an art-world con, an in-joke, a scam. It’s not so hard to accept the sincerity that underpins them; but it might take her a while to come to terms with the judgement and energy that go into them.

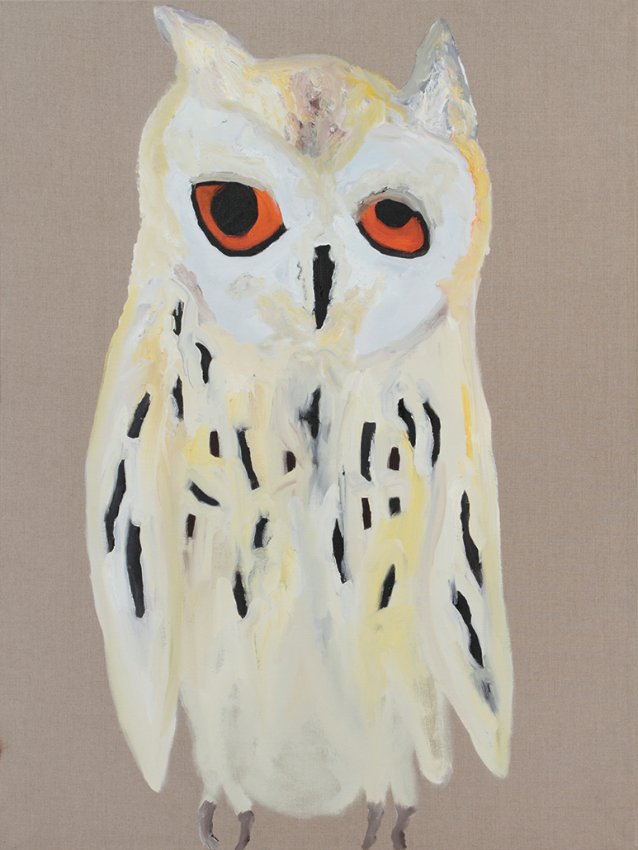

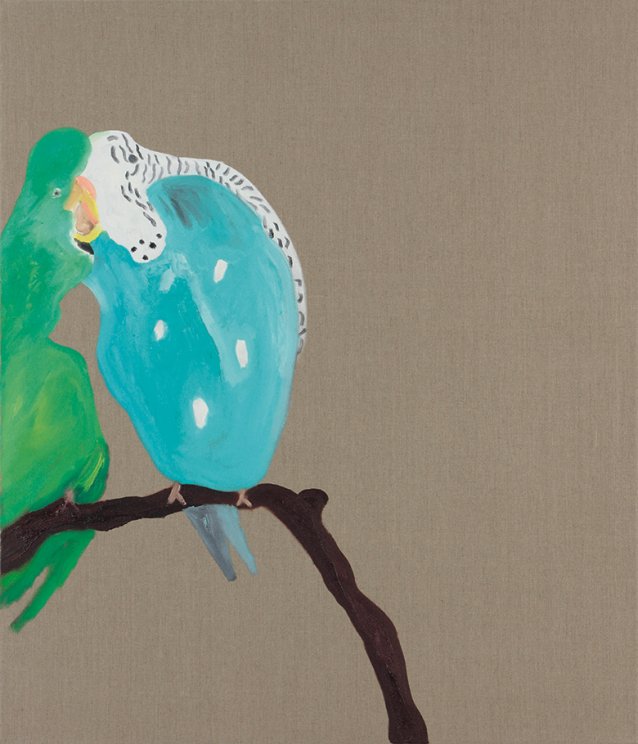

It sometimes happens that when artists live amongst a plethora of objects, elements of their real surroundings crop up again and again in their artworks. That household slouch Margaret Olley, for example, repeatedly combined and re-combined particular ornaments, vases, cloths, chairs, bowls in arrangements that she painted. But the contrast between McDonald’s heaving domestic space and his sparse canvases is striking. McDonald is very fastidious with his materials, using fine linen canvas and top-quality paint in very few colours on any one work of art. Although he paints rapidly, he doesn’t hurl paint on, in the manner of some expressionists. There’s a very sharp delineation between paint and bare linen, and his colours keep to themselves; there are no dribbles or smudges. Typically, his figures are isolated in untouched, or ‘negative’ space. So his Two parakeets, their small bright bodies merging, nibble at each other’s faces on a work in which two-thirds of the canvas is left entirely bare. There’s no English word for the effect the empty proportion has on our perception of the whole, although there is a Japanese one, which is ma. While the subjects in McDonald’s paintings may be gawky or abject, within the boundary marked out by the picture’s edges, the balance between the mass of the figures, their own undulating outline and the clear space around them makes for an elegant whole work of art.

McDonald gives his all to the painted outline, before colouring it in over the course of about an hour per picture. Let’s face it, he sometimes distorts anatomical elements: exhibit A, the stretched left arm of Jane Goodall; exhibit B, the rubbery, skinny and abbreviated right arm of the boy in the backwards snapback, holding the unfortunate cat Blackie. Further, his works show few signs of an academic study of perspective. It would be falling into the artist’s wily trap, though, to say that a child could paint his pictures. True, like some children’s, Darren’s figures seem to be laid down from the heart, impulsively, without calculation. Like those painted by children, they may be startlingly ugly and touching at the same time. When he’s worked with children he’s inspired them to achieve some joyous results. But children couldn’t bring forth Darren’s paintings. The observation that children commonly paint with cheap, non-toxic, water-clean-up paint on nasty paper, and their works are usually small, is not as glib as it sounds; McDonald’s luxurious mediums and startling scale are vital to the effect of his works of art. Invited to produce a body of work that distils the experience of physical closeness following trauma, or a series of works expressing the shape of affection, a group of children might produce many touching works, a couple of surprising ones and maybe a harrowing one. But to make his living in the cruelly tight Australian market for art, McDonald’s been producing series of works for exhibition and sale several times a year, for a long time.

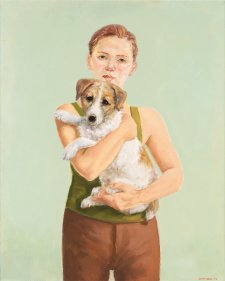

Sometimes, recently, McDonald’s been inspired by stories, photographs or advertising in the tabloid newspapers he reads; other times, he’s drawn on observation of people in his neighbourhood. In the course of his struggle with his neighbour, when he developed fears for Rupert’s life, he started collecting stories from the paper about urban attacks on domestic animals. The resulting series, which he called Something worth fighting for, expresses the artist’s exuberance and compassion in equal measure. In his painting Grace for Blackie, the cat, leaning out of its owner’s arms at a wild angle, has a pink stripe. The fact is someone in the suburbs speared the cat; the stripe, denoting shaved skin, is a legacy of surgery to remove the cruel missile and repair the wound. Likewise, the dog Mick was lost during a bushfire, and found his way back, somehow, later, to his devoted owner, Neil. Throughout this series, the paintings are perky; but for the most part, the backstory is poignant, sometimes depraved.

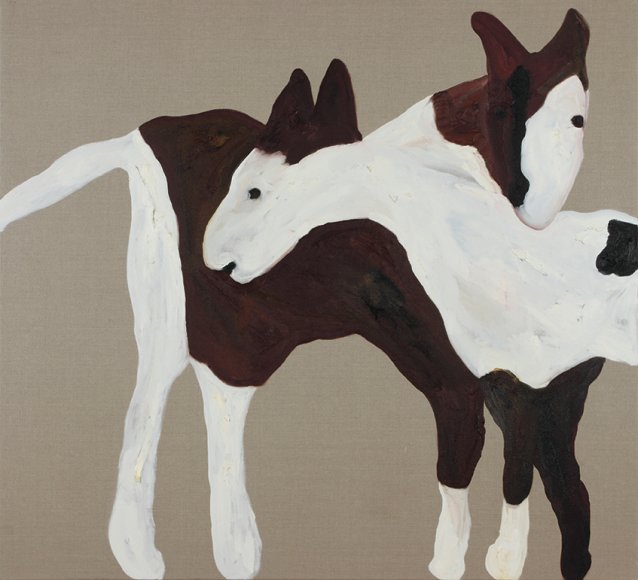

A look at the newspaper photographs and stories by which some of these paintings were inspired shows that facial likeness means little to Darren. Instead, the artist emphasises emotional states and ties through minute variations in his subjects’ crudely-painted eyes and bodies. Daniel seems defensive behind his protective goggles, his collapsed shoulders establishing his vulnerability; beside him, with twin gleams in his eyes, little Chopper stands steadfast. By contrast, seal-like Mick shows the white of one eye in fear; Neil’s hand draws him in against his body, protectively, but the man’s stricken, frozen face indicates a long battle of his own. On a more positive note, the gigantic dingo leans politely against a blissful Jane Goodall, tolerating her love-charged embrace a little sheepishly, just as dogs do. A different beast, Josephine’s cat – who has no more furry a face than Josephine herself, and looks something like a baby wearing a false moustache and a black skullcap with ears – scrunches its eyes in complacent cosiness in her arms, while Josephine brandishes her bundle proudly. The lineaments of the figures in all these pictures are expressive of tender connection; a continuous line encompasses the subjects in a space that they can claim as their own. You could say that in the pictures of the eminent Dr Goodall and the neighbourhood eccentric Josephine, the outer limit of the paint acts as a tight secondary frame for the figures: while the animal is held in human arms, the pictures are snugly contained within the outlines of human and animal. In The first time ever, inspired by a newspaper photograph of rare twin foals born in Gippsland, one little horse has its face against the other’s flank, while his miraculous sibling has her chin across his shoulders. While the news photograph of the foals - called Alise and Reynold - was a cheerful public image, broadly distributed, the mood of the painting is private, and soft. The way the creatures are intertwined is open to most humans only in the sweetest dreams.

In order to achieve the panache that characterises his pictures – which depends, to a great extent, on aspects of figurative representation that are ‘wrong’, like Goodall’s arm – Darren works constantly on the brink of wasting precious materials. He only gets one chance with a canvas; there’s almost never anything underneath what you see. Amongst painters whose work is detailed, painstaking, built up over time with much standing back and considering, there’s a lot of respect for McDonald’s capacity to achieve the effect of spontaneity. Many of them long for his ability to pull off wrongness with aplomb. It’s not some mysterious ability, though; he can’t work every day, because the process drains him. Besides, he can’t afford it; when a picture doesn’t work, when it’s wrong in the wrong way, that’s three or four hundred dollars down the drain. Darren’s life is quite hard. Still, asked what he’d be if he weren’t a painter, he answers without hesitation: ‘Unemployed’.