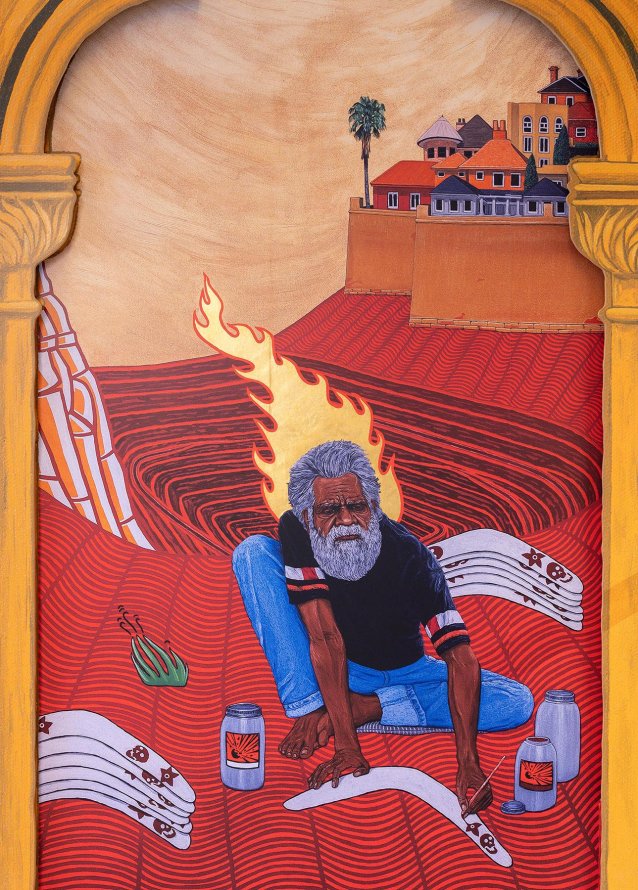

Prominently positioned at the National Portrait Gallery’s entrance, Marri Ngarr artist Ryan Presley’s ambitious new commission Paradise won celebrates the strength, survival and autonomy that resides within First Nations peoples through layered storytelling that speaks to history and contemporary experiences. Presley’s work is an invitation to pay witness and hold space for conversations that examine power, perspective and the ongoing residues of the ‘Colonial Project’.

Born in Mparntwe/Alice Springs and living and working in Meanjin/Brisbane, Presley first received acclaim for his series of watercolour paintings, Blood Money, in which he replaced the portraits on Australian banknotes with First Nations culture leaders. After completing his doctorate at Griffith University in 2016, Presley extended this body of work with Blood Money Currency Exchange Terminal, a performative installation which invites audiences to exchange Australian currency for Blood Money Dollars, with the money raised given to First Nations youth organisations.

In Paradise won Presley builds on a form of visual communication he has been working on since 2020, using research-based narratives and power-loaded imagery. In this work he looks to align to the ways religion leveraged artmaking as a teaching tool. Refracting and subverting this, Presley traverses the tensions between the contemporary now and immemorial histories with a finetuned criticality. Presented in a series of large golden archways which refer to Western, religious iconography and signify a sense of worth and majesty, Presley’s beat of heroic First Nations figures engage in acts of resistance, confrontation and escape.