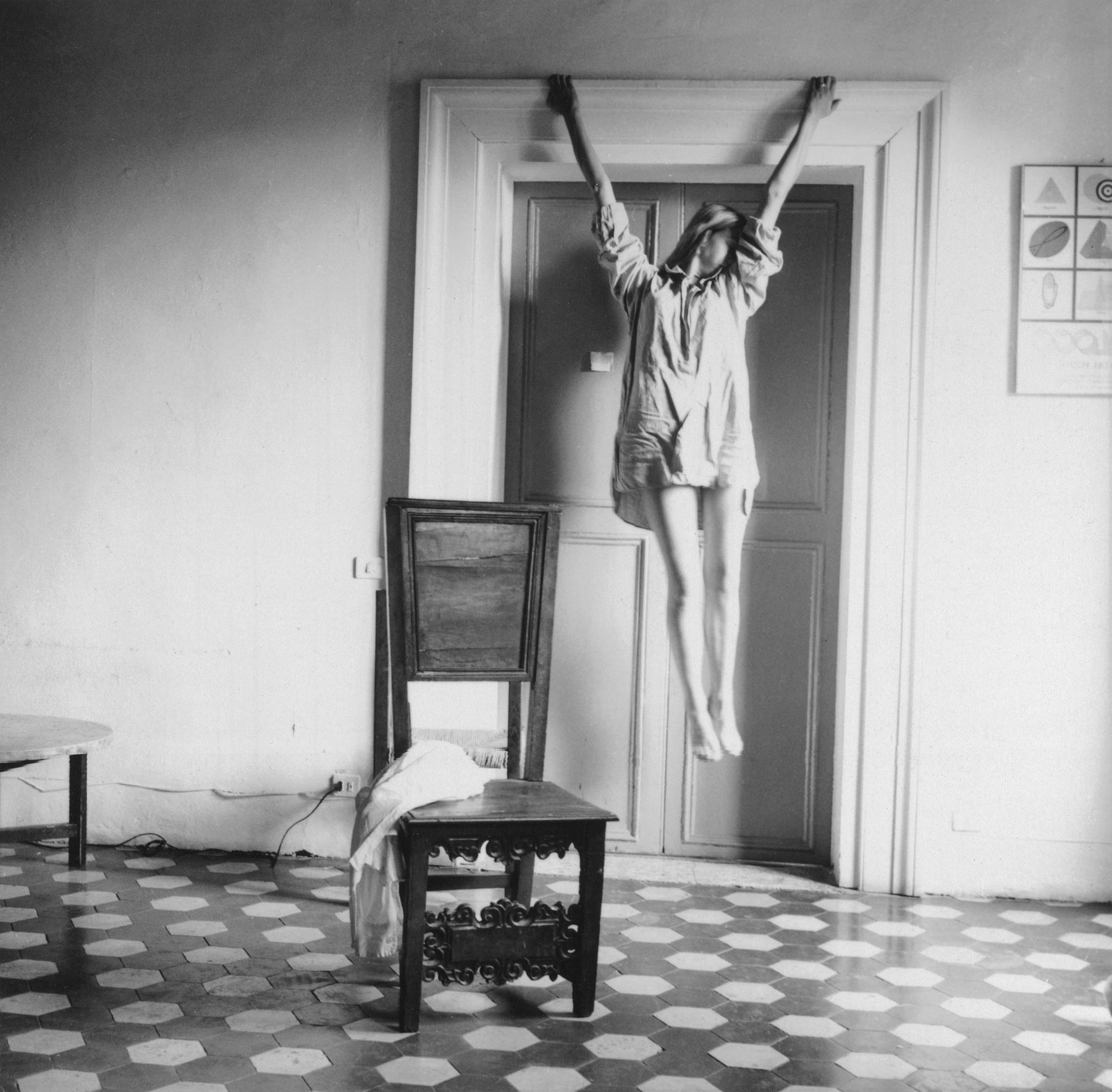

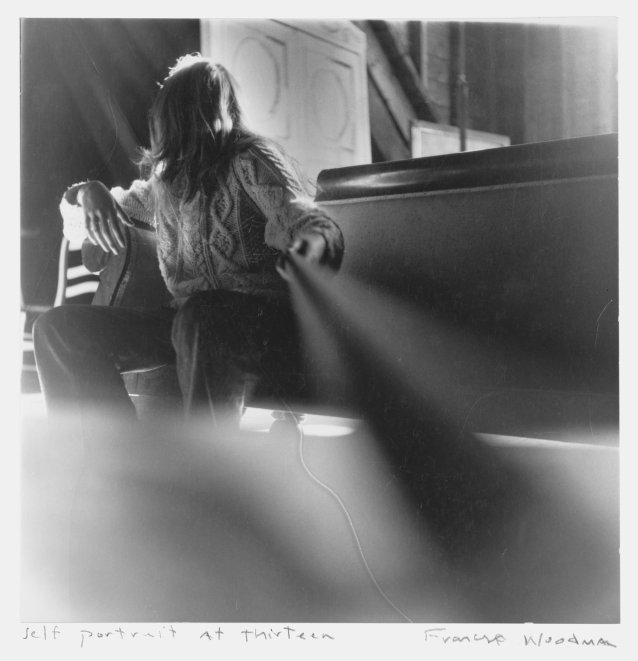

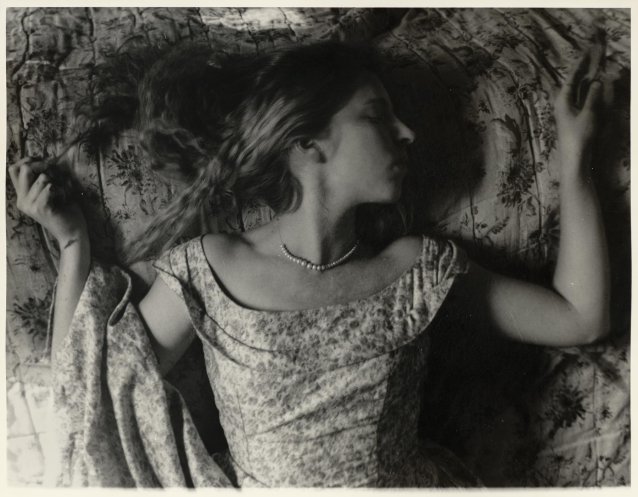

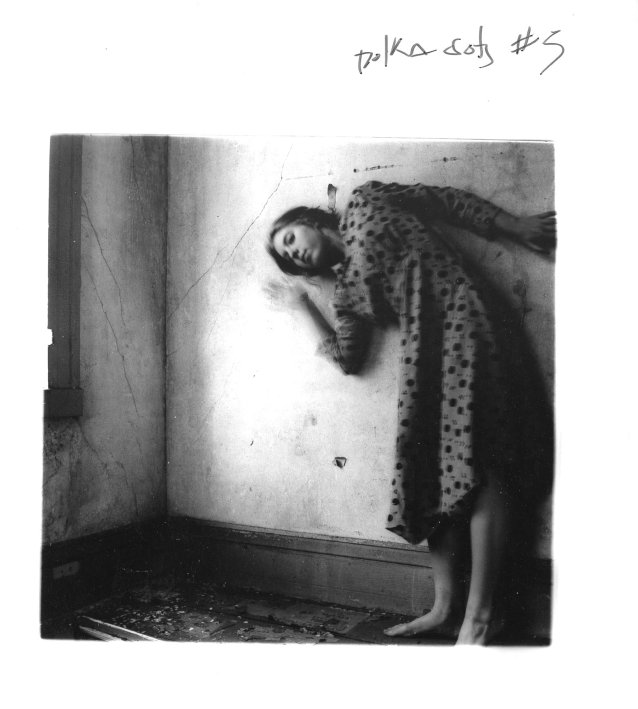

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron are two of the most influential women in the history of photography. Living a century apart – Cameron working in England and Sri Lanka from the 1860s, and Woodman in America and Italy from the 1970s – both women explored portraiture beyond its ability to record appearance. Positioning their work together in a way never seen before, the exhibition Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, on show at the National Portrait Gallery, London from 21 March to 30 June 2024, spans the careers of both artists, showcasing more than 150 rare vintage prints.

- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning