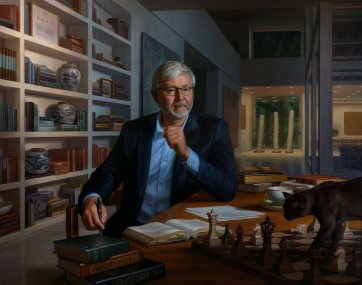

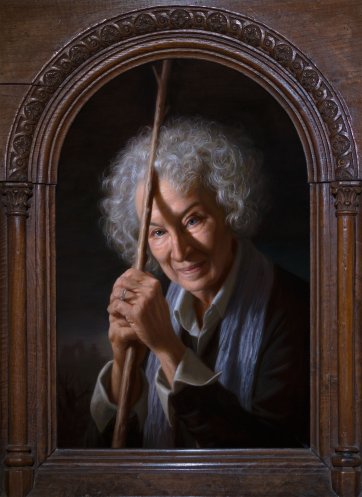

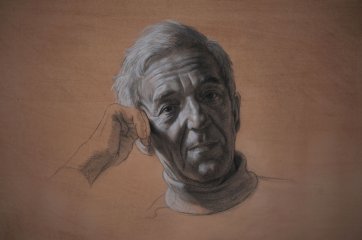

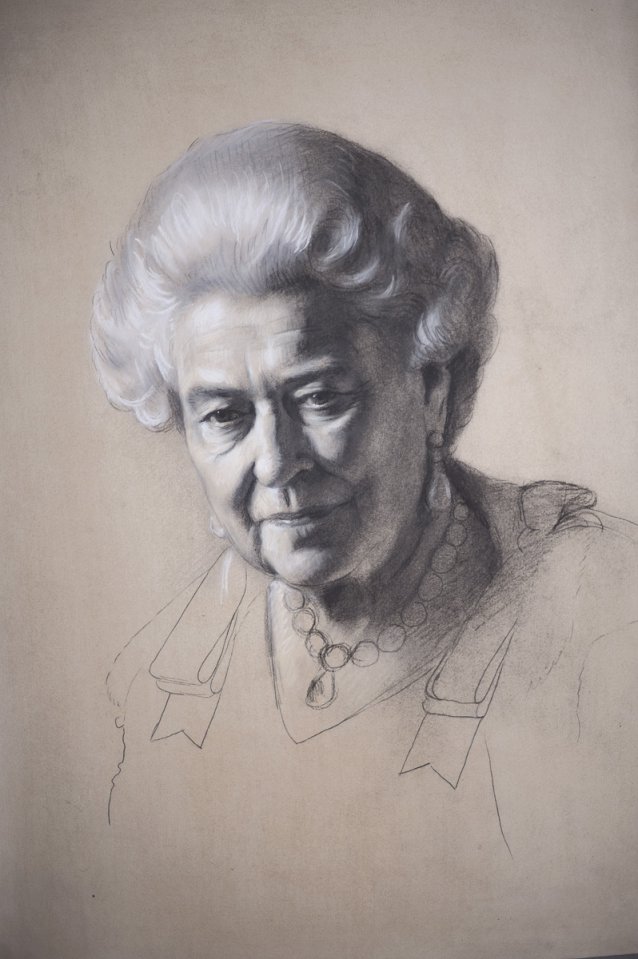

Ralph Heimans AM says that his definition of a successful portrait is one that elicits an emotional response, and one that makes you feel as if you know something about its subject. Going beyond what they look like and what they do – as some of society’s most significant and influential people – to what it is that makes them human, to the characteristics that connect us. ‘As an artist, the creative instinct is that you try to move people,’ Heimans says. ‘The worst thing you can get is no reaction.’ Over the nearly three decades since he completed his earliest major portraits, he has perfected an approach to portraiture that asks more questions than it answers, prompting viewers of his works to share his own experiences of his sitters and using a combination of narrative and insight to create portraits that are united in their mysterious, magnetic quality.

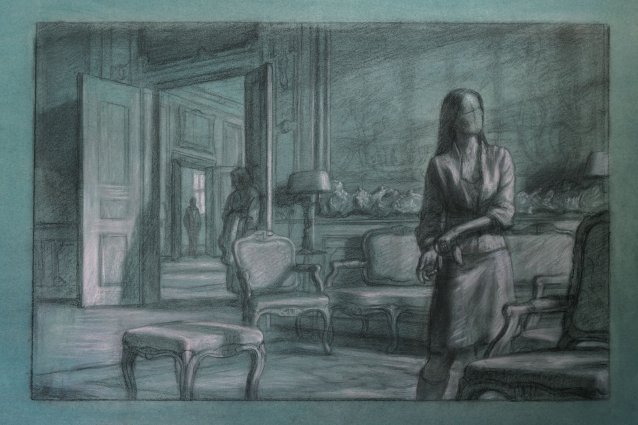

Sydney-born Heimans is something of a rarity in being an artist whose focus is solely on portraiture and who, in consequence, has become adept at toying with the precepts of what many are inclined to think of as an inflexibly traditional genre. He has said that some of his earliest memories are of ‘sitting alone and drawing incessantly’, and that he knew from the age of 14, when he tried oil paints for the first time, that he’d found his calling. At 17, he won an award that funded travel to Europe, where exposure to the great museums and collections steeled his determination to pursue a career as a painter, but where he found leading art schools to be disdainful of realism and therefore didn’t offer rigorous tuition in technique. After returning home to Sydney he did one year of a degree in architecture before switching to the seemingly unusual but definitely fortuitous combination of fine arts and pure mathematics. ‘When you paint in a realistic manner, it’s very scientific, very empirical,’ Heimans says. ‘You have to observe how light falls, how textures can be represented in paint … [plus] the illusion of three dimensions is absolutely critical to my work.’ Studies at Sydney’s Julian Ashton Art School and extensive private tuition strengthened his skill in the technical aspects of his craft. Equally, however, Heimans has always thought of himself as a ‘left brain artist’. To create, he says, is emotional, and to engage only in portraiture – the art of the human encounter – requires empathy, an understanding of character which he translates onto canvas via the individual narratives he researches and develops for each of his subjects to the point of obsession. Nothing in his meticulously realised paintings is incidental or trivial or extraneous. Every one of his portraits is embedded with a reverence for and comprehension of the techniques of his art historical antecedents. Every element of every work – setting, story, symbolism, perspective, draughtsmanship – conspires to result in distinctive portraits that combine visual impact with insight, delicacy and detail.