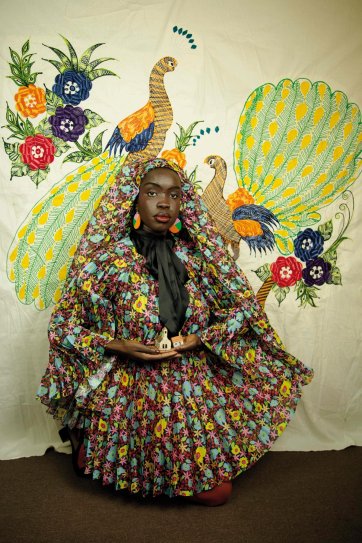

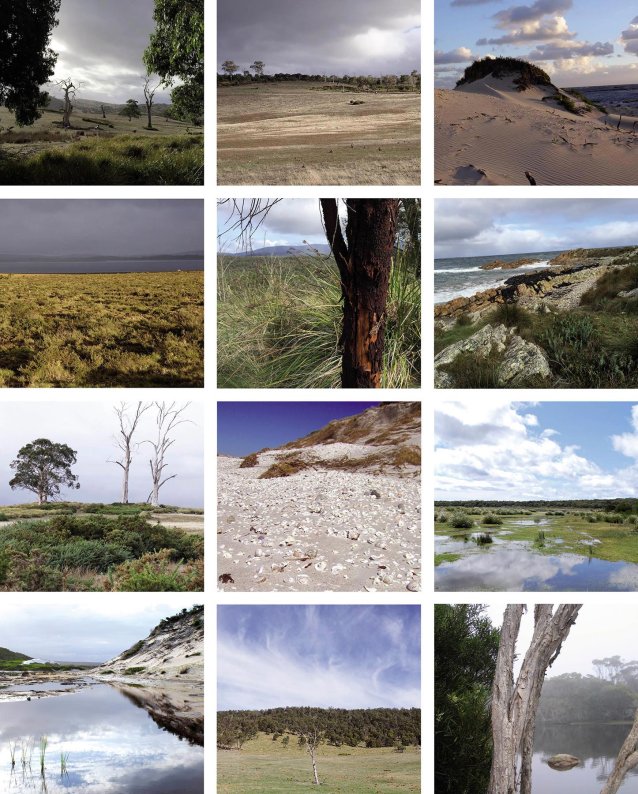

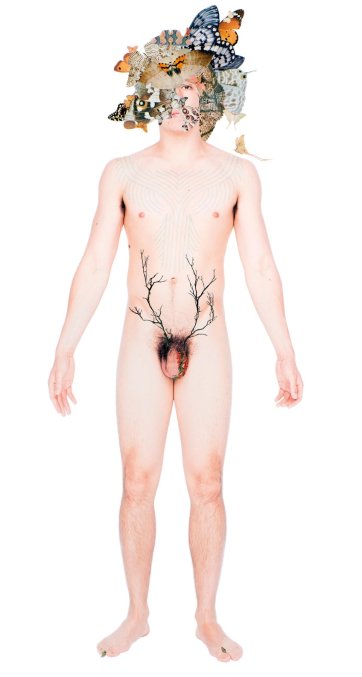

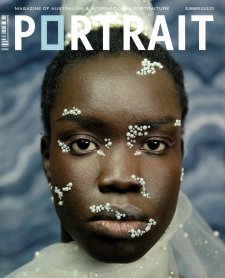

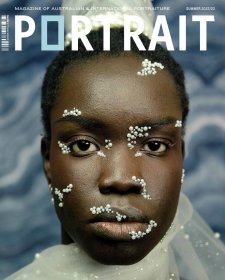

Portrait23: Identity is an invitation to stretch, push, resist and break through the constraints of portraiture. We asked artists from diverse practices across Australia to propose concepts for portraits without assumptions, expectations or boundaries – only the abstract notion of identity as a broad underpinning. The ‘23’ in the title denotes the year of the exhibition, but, by accident rather than by design, it is also 23 artists and collectives who make up Portrait23: Identity. For us as curators, one of the strangest and most satisfying things about bringing this exhibition together has been the remarkable and specific parallels that have formed across the works by Abdul Abdullah, Alison Alder, Arts Project Australia, Atong Atem, Baby Guerrilla, Christopher Bassi, Kate Beynon, Mia Boe, Tarryn Gill, Julie Gough, Amrita Hepi, Naomi Hobson, Deborah Kelly, Fiona McMonagle, Angelica Mesiti, Dylan Mooney, Nell, Sally Smart, Vipoo Srivilasa, ‘stArts with D’ Performance Ensemble, Latai Taumoepeau, Yarrenyty Arltere Artists and Kaylene Whiskey. With such a broad brief, one might imagine a disparate array of works would emerge. While the portraits are indeed wonderfully various, some remarkable patterns of thought, metaphor and materials emerged to intrigue us.

Given autonomy and creative freedom, the artists have come to us with reflections on who they are and what it means to represent themselves, their community, history and contemporary society. Free from tight thematic directions, they have all engaged in a reflexive, introspective and subconsciously grounded exercise in finding meaning in an approach to portraiture that connects deeply to their practice. These works demonstrate the multiplicities of identities that coexist simultaneously and chaotically within each of us. For the visitor, the portraits invite a human response – not a pedagogic, hierarchical positioning, but comprehension grounded in instinct, feeling and connection. The most striking consistency between many of the works is the way that identity is embedded within performances of imagined selves rather than static portrait objects. Storytelling within this context becomes the active force of belonging and situating the self within overlapping identities. In these works, individual identity is a dynamic and active process embedded within longer cycles of collective storytelling, and takes concepts of portraiture along for the ride. Portraiture here offers the capacity to embrace notions of self and explore representations that exist outside of rationality grounded within private realms. This is evident across all of the works and we have selected a few examples to share here.