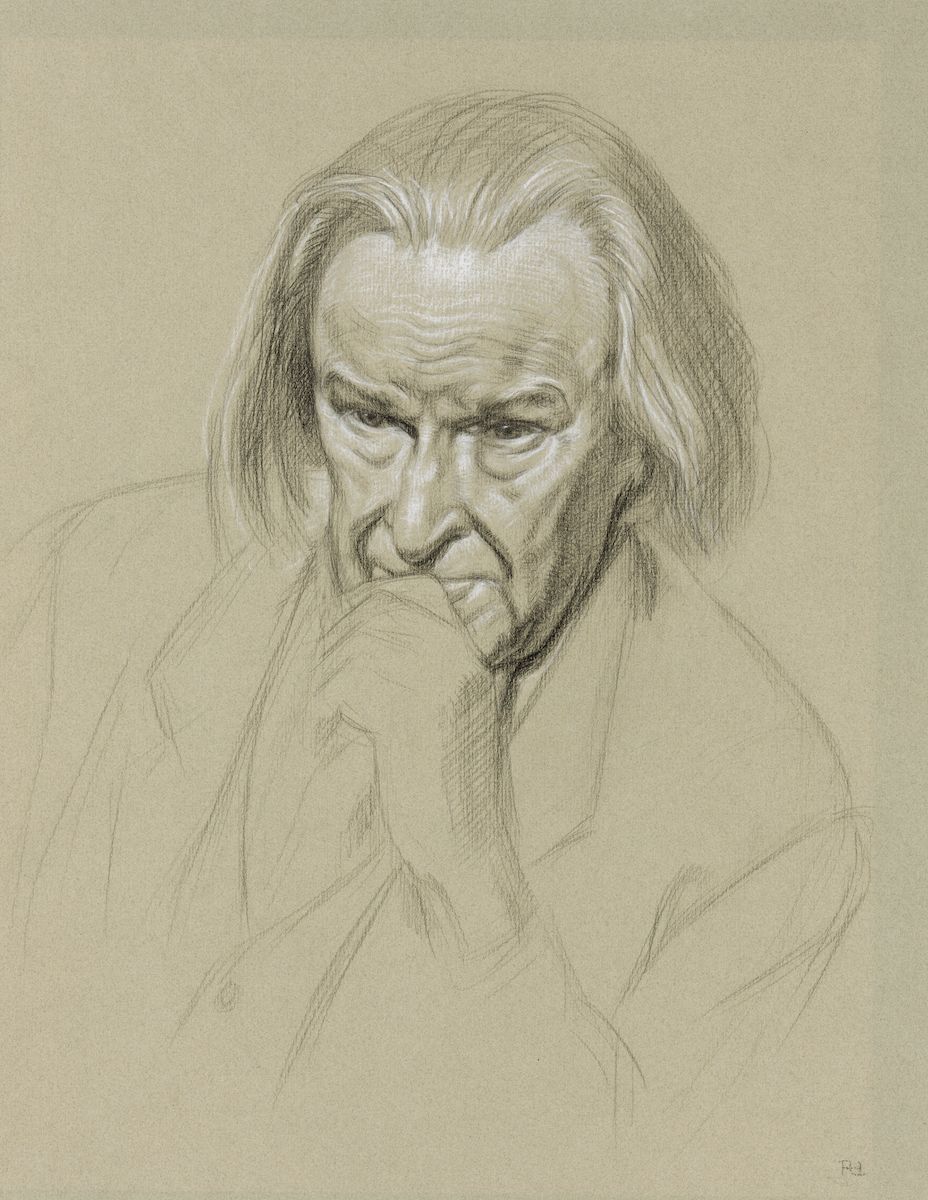

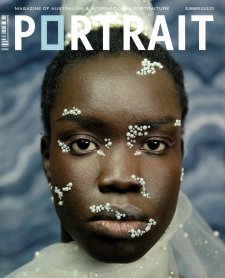

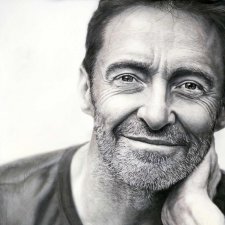

Portrait of Professor Derek Freeman, 1996 Ralph Heimans AM. © Ralph Heimans

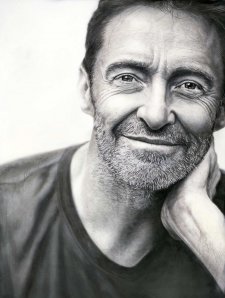

Drawings are often thought of as inferior to paintings in various respects. Search for ‘drawings’ in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection database and you’ll find a list of around 400 objects from the past two centuries, many of which have titles or descriptions incorporating words like preliminary, preparatory, ‘study for’ and sketch, underlining that drawings are often considered a means to an end. A quarter of the 400 are drawings made because their subjects weren’t available to sit for their portraits for long, and a significant proportion of that 100 are works that have never been displayed and are only ever seen by curators. Artists observe, capture and compose on paper so that they can create ‘the portrait itself’ in the studio later, assigning the drawings a slighter status. Conservators are wary of drawings because paper is so susceptible to damp, light, fire, pests and neglect, and because it distorts, discolours, tears or creases. Mediums like pastel, charcoal and watercolour can be fugitive or friable, and registrars are wont to remind curators that displaying a drawing will come at the cost of months of rest for the work thereafter. It’s these latter things that perhaps chafe most with me, for whenever I’m challenged to itemise my favourite things in the collection, drawings invariably make the list. And not just because of my weakness for particular eras, artists and styles, but because drawings seem to be able to pin down the relationship at the core of any portrait, as if you’re seeing with the artist’s eyes at the precise moment that their connection with the sitter takes place.

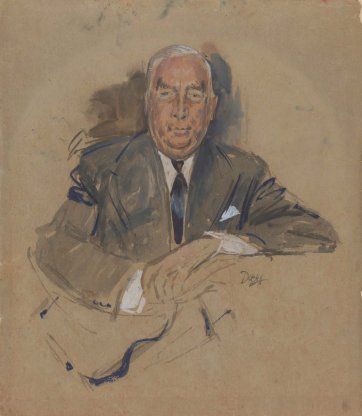

1 Sketch for Prime Minister Robert Menzies, 1960 Sir William Dobell OBE. © William Dobell/Copyright Agency, 2024. 2 Jessie Whyte, c. 1840 Thomas Bock.

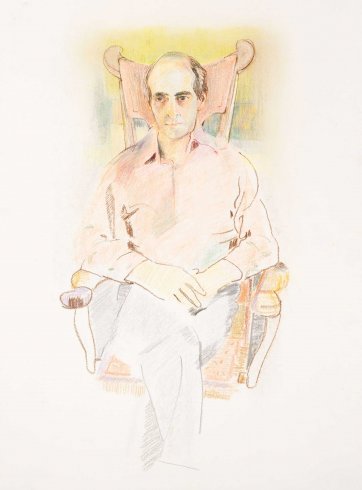

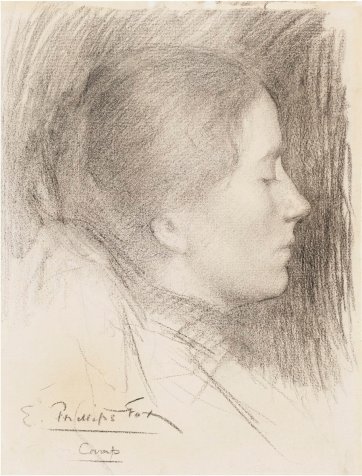

Ralph Heimans, for example, might spend five or six months working on each of his luminous and breathtakingly accomplished paintings, having devised a complex, rhythmic composition designed ‘to hold the viewer’s attention on the soul of the portrait’: the subject’s face, captured on paper, often in instances when they’re unguarded, introspective and most themselves. His 1996 portrait of anthropologist Derek Freeman was made in preparation for a painting of the sitter which never eventuated, but the artist considers the drawing his ‘most successful attempt at capturing Derek’s obsessive, determined spirit’. E Phillips Fox’s quiet drawing of artist Ina Gregory was made during one of the summer schools he hosted at Charterisville in the 1890s, possibly in preparation for his painting Art Students (1895). William Dobell only got about 40 minutes in total with Sir Robert Menzies when he was commissioned by Time magazine to create a portrait of the then Prime Minister in 1960. With no time to get to know his sitter, Dobell instead made a number of swift watercolour sketches of Menzies that nevertheless snared his ‘salient mannerisms’ with freshness, frankness and economy, undiminished by the distance implied in the solidity of the finished work. ‘I always paint, as I think, a straight portrait,’ Dobell said in 1961, ‘and I think I got a fairly good job done in the time allowed me.’ Erwin Fabian’s deft and rapid portrait of his friend Klaus Friedeberger was made in January 1942 when artist and subject were being held in an internment camp in Hay, New South Wales. Berliners by birth, both men had fled to England in the late 1930s to escape persecution, only to find themselves declared enemy aliens and deported to Australia aboard the troopship Dunera in 1940. Both men made art onboard and continued to do so as detainees, Friedeberger making over 200 watercolours and Fabian drawing and painting with watercolour and whatever else he could get his hands on. Rosemary Madigan’s pastel drawing of her partner Robert Klippel is infused with a softness and intimacy that rarely, if ever, comes across in the many portraits made of him. In Madigan’s drawing, we see his private self – not the brooding artist-in-his-studio surrounded by examples of his industrial, abstract sculptures, but the man-at-home wearing a favoured pink shirt. Madigan was especially proud to have created a portrait that ‘reflected her own special insight and experience of his personality’.

1 Klaus Friedeberger, 1942 Erwin Fabian. © Estate of Erwin Fabian. 2 Robert Klippel, c. 1990 Rosemary Madigan. © Rosemary Madigan/Copyright Agency, 2024.

Immediate, authentic and vital, drawing – unlike painting and sculpture – has been a feature of the work made by European artists in Australia from the outset, and not merely because it was an available and efficient means of documentation. Portraits, more to the point, along with topographical and natural history illustrations, were the first things newcomer artists made in early colonial Sydney and Hobart, and by the 1830s portraits constituted the lion’s share of their output, with specialist draughtsmen such as Thomas Bock and William Nicholas catering to the pretensions of increasingly cashed-up, aspirational colonists. When Bock, who came to Hobart as a convict, died there in 1855 it was noted that his portraits ‘comprise several beautiful works of Art, and adorn the homes of a number of our old colonists and citizens’. Nicholas trained in lithography and engraving in his native London before immigrating to New South Wales in 1836 and by 1847 it was said that he had ‘more heads offered to him for decapitation than he is able to take off’. Works such as his portrait of Alice Want demonstrate how Nicholas combined the delicate stippling technique characteristic of miniature painting with the fluid gestures of larger watercolours to create portraits that were known for their ‘remarkable correctness in drawing’ as well as ‘freedom in action and position, and their clearness of tone and high finish’. The lion’s share of both artists’ extant portraits are on paper, demonstrating that practitioners in places as remote and supposedly blighted as colonial outposts pursued drawing as a preferred, authentic mode of expression and not just a practice suited to non-aesthetic purposes.

1 Alice Want, 1853 William Nicholas. 2 Ina Gregory, c. 1895 E. Phillips Fox.

From the late nineteenth century onwards, regular exhibitions of works on paper contributed to the continuation of the idea that drawings, including studies and preparatory sketches, were artworks in their own right. For a national collection that strives to encapsulate the unique qualities of portraiture and the multiple ways that artists have always practiced it, the longevity, intimacy and potency of drawing plays a crucial part.