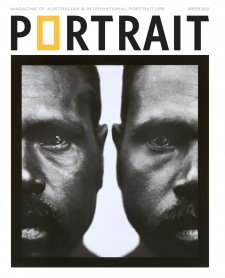

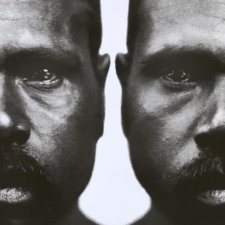

In March, I and my fellow judges for the 2022 National Photographic Portrait Prize selected a work by Chris Budgeon for inclusion in the exhibition. I sat down for a chat with the Canadian-born, Melbourne-based photographer to discuss his works and career.

Sandra: Let’s start by going back to how you began as a photographer;

it is a pursuit that you embraced from early on, isn’t it?

Chris: When I was at college, I shot bands; so I can say I started in the music industry. A friend (who is still in the industry) used to take me to showcase gigs. We were just babies, and we’d go to the clubs and bars in Toronto and Montreal, and down to New York, to CBGBs. And so now I have this amazing collection of images of bands in tiny venues from a certain – now historical – period. Maybe five years ago, my partner’s band opened for Devo. I met Mark Mothersbaugh [lead singer] and we got chatting. I said, ‘You know I saw you in 1978 in a little bar in Montreal.’ And he went ‘Club Soda.’ I said, ‘Yeah that was it.’ He asked if I still had the photographs and gave me his email address. I found them, two rolls of colour and a roll of black and white, and a year later I get a call from the Museum of Modern Art in Denver – they wanted my photographs for an exhibition. I was literally a 19-year-old kid taking pictures, and then 40 years later they’re in this exhibition touring around the world.

I am still interested in musicians, and I do photograph them whenever I get the opportunity.

Fast forward to today, and you appear to have created a balance between commercial work and your artistic output. Do you find that one side of your practice might inform the other? For example, a commission might inspire the direction you go in next time you start playing with your own creative output?

I’d say it’s the other way to be honest. I find my own work, my own practice, that’s where I get to experiment, and that’s where I try new ideas. Quite often if I have developed an example of that, I can take it to a client who commissions me for work; I go ‘What do you think about this look, etcetera.’ So I would say it travels back the other direction. If I haven’t seen an art director in a while, the first thing they ask me is ‘What are you up to? What projects are you working on?’ That’s the work they’re interested in and want to see. I’m very lucky because my vocation is my avocation. I can make a living at commissioned work. But really, I always secretly think that it just funds my other work. For my own work, I don’t need to compromise. I can just do what the bloody hell I want.