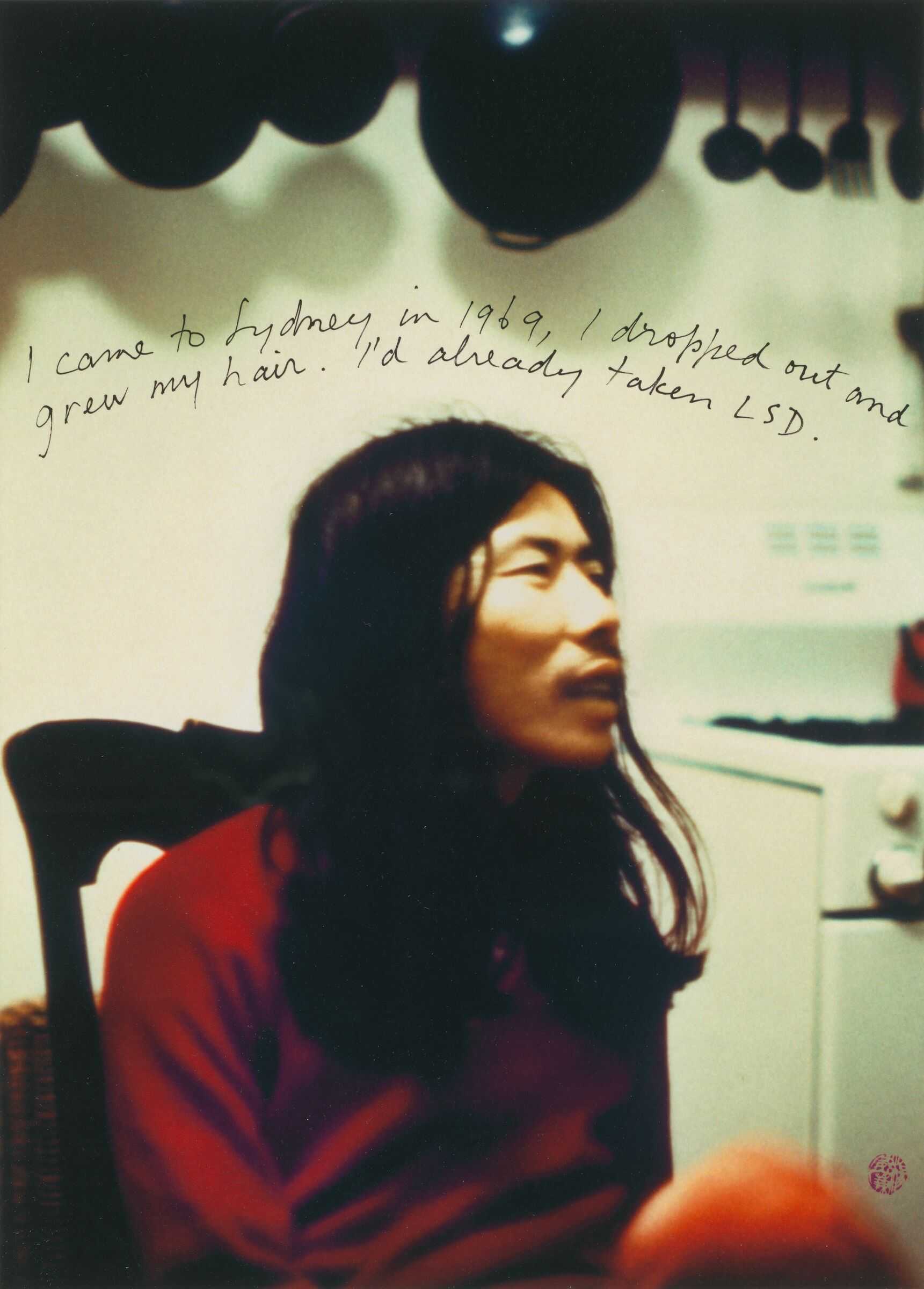

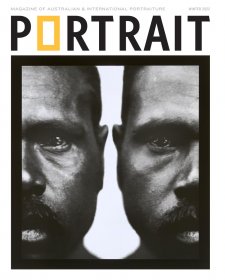

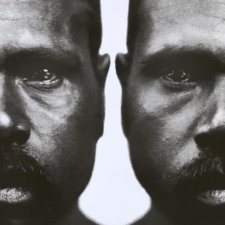

William, Randwick, 1975/2008 William Yang, Melody Cooper. © William Yang

I grew up on a tobacco farm at Dimbulah on the Atherton Tableland. About twice a year, in the fifties, we’d travel down to Cairns to visit Aunt Bessie (my mother’s sister) and my cousins in her big house in Lake Street – it was family headquarters. I knew Aunt Bessie was a widow and I’d seen old photos of her late husband William Fang Yuen in the living room. My mother, in an unguarded moment, told me he had been murdered, but would not tell me any of the details.

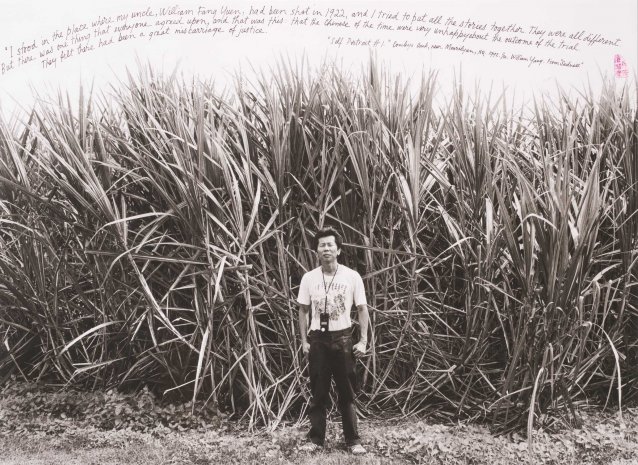

I always wanted to find out more about my murdered uncle so years later in 1990 I drove up to North Queensland to interview my relatives. I discovered that my uncle was wealthy. He owned a shop and cane farms around Mourilyan, but in 1922 he was shot by a White Russian called Peter Danelchenko who was a manager on one of his farms. There was a trial and Danelchenko was acquitted of first-degree murder. The Chinese at the time were very upset about the outcome of the trial because they perceived it was a miscarriage of justice. Killing a Chinaman was not considered a serious crime.

My uncle had been shot in a hut on his cane farm, and I located the place. The hut had long since gone but as I stood there in the cane fields in the place where he had died, the past and the present somehow came together and it was a significant moment in my life. A whole lot of things about my upbringing made sense to me. Why my mother so strongly thought that being Chinese was a complete liability and why she brought us up to be more Australian than the Australians. I wrote on that photo and called it Self Portrait #1.

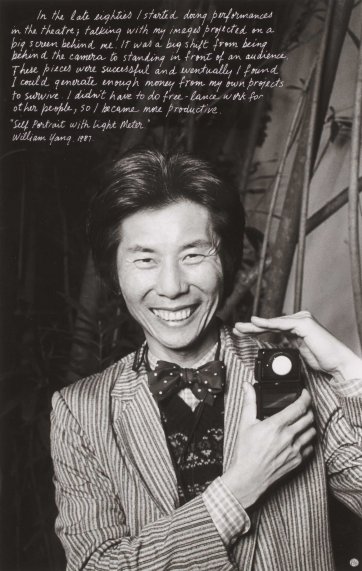

I had been doing monologues with image projection in the theatre since the late eighties. My third piece Sadness (1992), about people from the gay community dying of AIDS, intercut with the story of my murdered uncle, was very successful and toured Australia and the world. I kept doing the monologues because overseas entrepreneurs wanted them and they became the main expression of my work.

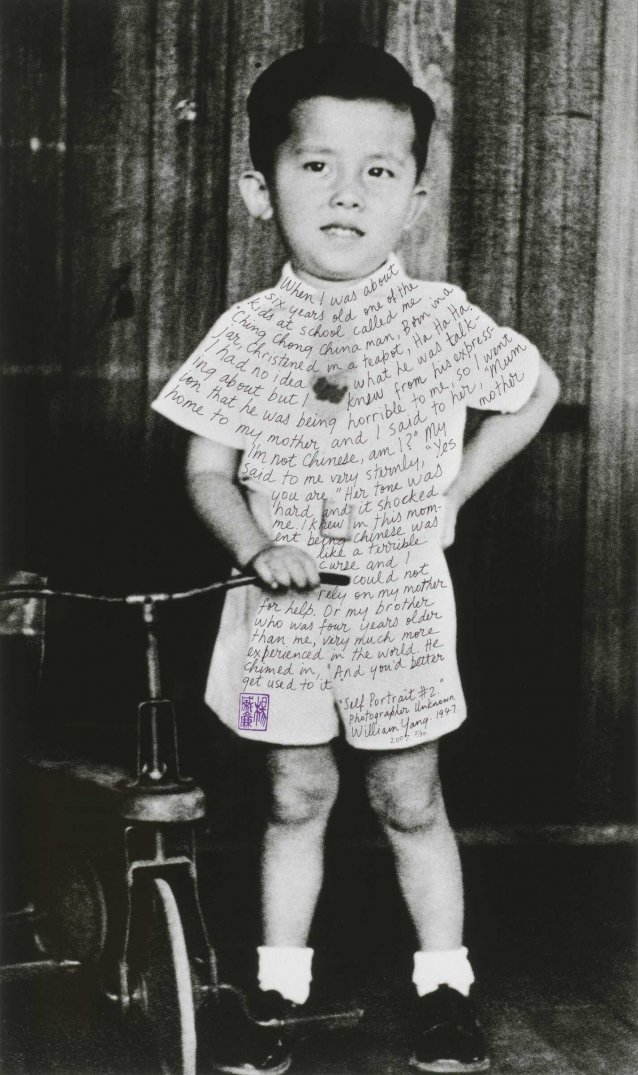

From the performances I found that many of my images had stories to them. When I came to exhibit these same images as prints in a gallery, I wanted to acknowledge the stories, so I wrote them directly onto the print. One of the stories from Sadness was key to my sense of identity. When I was about six years old, one of the kids at school called me Ching Chong Chinaman. I knew he was being horrible to me so I went home to my mother and said, ‘Mum I’m not Chinese, am I?’ She replied harshly, ‘Yes you are.’ It shocked me. I’ve never forgotten that moment so I wrote this story on a photo of myself as a child and I called it Self Portrait #2.

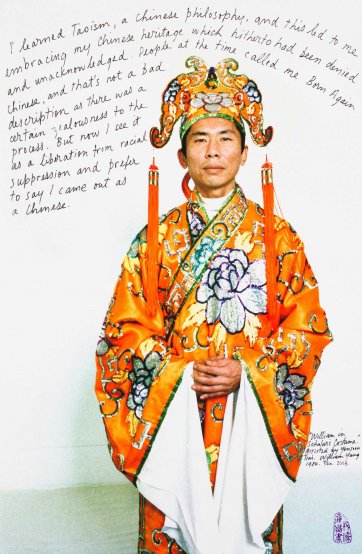

1 William in Scholar's Costume, 1984/2008 William Yang, Yensoon Tsai. 2 Self Portrait with Light Meter, 1987/2007 William Yang. Both © William Yang

I came out as a gay man in the early seventies. I didn’t consciously do it, I was swept out by events at the time. I found this act of being visible had its drawbacks in the wider world, but it politicised me. I became more aware of the process of sexual suppression and liberation, and I began to think about race, how my Chineseness had been stifled both by my mother and by the white, mainstream society with which I identified. So gradually I claimed my Chinese heritage, albeit Australian–Chinese heritage, and I did the piece William in Scholar’s Costume (1983), where I say, ‘I came out as a Chinese.’

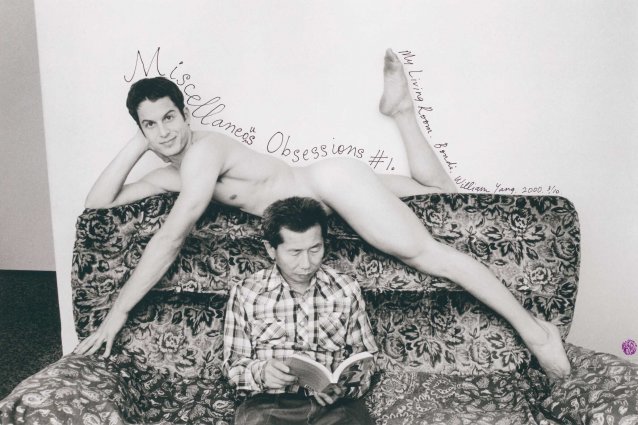

I’ve always photographed attractive men either nude or semi-nude, it’s one of my enduring, guilty pleasures. Around 2000 I started putting myself into the picture as well, just as a fun thing to do. Many nudes exist mainly for the viewer’s lustful gaze, but I change the dynamics of the scene when I’m there as a presence as in Miscellaneous Obsessions #1. I become a character in my own story, slightly oblivious to what is around me, and absorbed in a book, Fairyland. The naked figure could be read as a figment of my imagination.

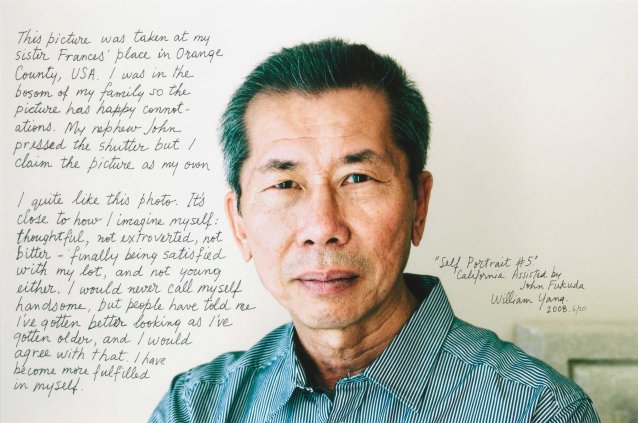

My most recent self portraits are more philosophical. I’ve never really liked my appearance but in Self Portrait #5 I come to terms with the way I look. The self-portrait genre lends itself to reflection and thoughts about mortality. As I continue to do more, my self portraits are about milestones in my life, some more important than others, but each contributing to a memoir.