‘“Love” is the name for our pursuit of wholeness, for our desire to be complete.’

Plato (as Aristophanes)

Around 380 bce, the Greek philosopher Plato explored the virtues of love in his work Symposium, with a variety of noted speakers contesting the subject. The playwright Aristophanes delivers a speech, proposing that every person is only one half of an original whole, split apart by the gods and fated to long for the other part of themselves. Aristophanes goes on to say: ‘And so, when a person meets the half that is [their] very own, … then something wonderful happens: … a sense of belonging’. While Plato’s focus may be on romantic love between two people, the concept of ‘our desire to be complete’ is just as applicable when considering the love felt within communities, families and friends.

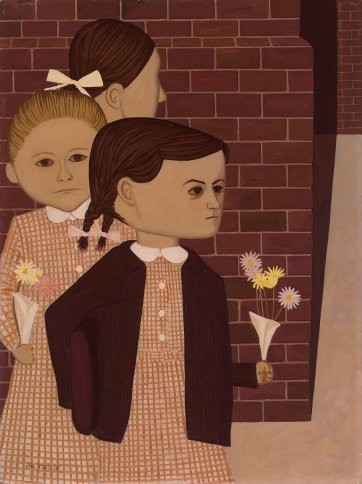

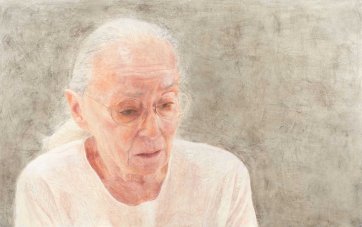

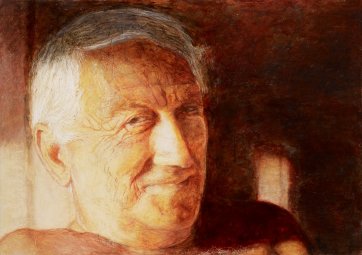

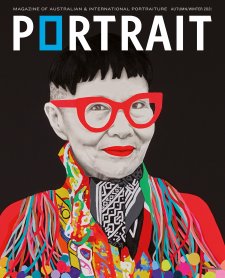

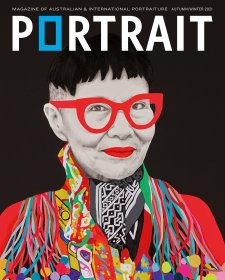

And so it is in the National Portrait Gallery’s 2021 autumn-winter exhibition Australian Love Stories, with portraits brought together to explore real-life vignettes that survey love’s diverse forms, from the 1800s through to today. An exploration of the Gallery’s collection subjects produced a wealth of relationships, and these were supplemented by inviting more ‘nearest and dearests’ from lenders and other collections. The result is an exuberant montage that more that scratches the surface of the notion of ‘love in all its guises’.

The hearty medley emphasises, too, that a portrait need not be a static, staid representation; at any moment it has the potential to be a window through which we discover elements of people’s lives, and common (or not so common) experiences. Connections can be formed between the artist, the subject and the viewer, by exploring aspects of their history, or lived experience. Wherever such connections can be created, portraits have the capacity to preserve these moments of love – whether infused with passion, loss, inspiration, community, friendship, or family – becoming chronicles and keepsakes.