- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

You may not have heard of (or have only a vague idea about) John and Elizabeth Gould. If you are old enough you may have been a child member of the Gould League of Bird Lovers. If you’re a cabinet minister you may occasionally look beyond the prime minister and ponder the origins of the Gould bird prints adorning the walls of the cabinet room. If you’ve visited the National Portrait Gallery, you may have seen the portrait of John on the walls; or you may have heard that he is known as ‘the father of Australian ornithology’, enjoyed budgerigar pie, or that it was he who brought to Charles Darwin’s attention the subtle differences and similarities in those avian exemplars of evolution, the Galapagos finches. Or maybe you have an idea that Elizabeth was a beleaguered wife whose artistic talents were overshadowed by the brazen ambition of her husband.

For my part, I declare myself a fan of the pair (a sentiment held long before I came to live in Australia), although I hold a particular, personal attachment: my home was a pictorial menagerie of exotic birds and animals inherited from John and Elizabeth’s only grandchild, who was my great grandmother. Living in Australia has only deepened and made more complex my connection to them; now I prickle with indignation when I hear Elizabeth’s agency being underestimated, and at the same time I am deeply uncomfortable as I trace my forebear’s role in the colonial appropriation of Australia. Their lives and times, both dark and light, are woven into my family stories and portraits.

My aunt has a family scrapbook of memories by John and Elizabeth’s eldest daughter, Eliza, compiled for her daughter in 1885. Eliza recalls, ‘To begin at the beginning as children say, I hardly remember our Mother, being only 5 years and 4 months old when she died, but all who spoke of her said she was indescribably sweet looking, a good and accomplished woman and an affectionate wife and mother. The oil painting I have of her, with her hair done high up in a bow and a cockatoo on her finger, was taken after her death, from another my sisters have. The bird was one they brought home with them from Australia and was many years a pet. It used to whisper, “pretty boy”, the only thing it could say, and we girls were a little jealous; it never said “pretty girl!” Our mother died at Egham, when Sai was 4 days old and not long after their return from Australia.’

The ‘green’ portrait of Elizabeth, as my family calls it, resonated throughout my childhood. Perhaps because she died so young I imagined her children bereft and staring longingly at it. Her gentle gaze has drawn me into other worlds during formal teas with my grandparents, and, in recent years, looking over at the portrait while watching television with my mother. I ruminate: while Elizabeth is depicted as a Victorian beauty with the full romantic flourish of warm tones and an indistinct landscape behind her, it strikes me that truth-telling can reveal itself slowly; it is multi-layered. On her hand, she holds the weight of a cockatiel, something from somewhere else.

From 1838 Elizabeth and John spent two years in Australia exploring and collecting specimens and information for what would become their illustrated folios of The Birds of Australia and The Mammals of Australia. The Birds of Australia was an audacious ten-year effort incorporating 602 lithograph plates, most of which Elizabeth had sketched, and half of which introduced bird species unknown to people outside Australia.

Elizabeth weighed the sacrifice with the outcome. She wrote regularly to her mother and cousins, into whose care they had left their three smallest children. Their elder son – eight-year-old Henry – and a nephew accompanied them to Australia. While this separation was deeply stressful for all concerned, it was not unusual; children from large, poor and wealthy families alike were routinely cared for by extended family. Against a trend of opinion, I see Elizabeth Gould not as a victim but as a woman of dry humour and adventure who chose her partner – surely a more interesting love story. While Elizabeth travelled and worked alongside her husband, it became necessary for her to remain for eleven months in Hobart as the guest of Sir John and Lady Franklin at Government House, during her confinement and the birth of her ‘little Antipodean’. Lady Franklin shared Elizabeth’s natural energy and fascination for the natural world, and Sir John became young Franklin Gould’s godfather.

Never idle, Elizabeth wrote to her mother on 9 January 1839: ‘I find amusement and employment in drawing some of the plants of the colony, which will help to render the work on Birds of Australia more interesting … I trust we shall be enabled to make our contemplated work of sufficient interest to ensure it a good sale.’

As it turned out, Elizabeth was on the mark; the folios were at the cutting edge of ornithological and zoological illustration, not only because of the invention of lithography, which enabled multiple books to be sold, but because they drew birds and animals in habitat and from life – as exemplified by this sumptuous depiction of the Philip Island parrot. It was John’s observations, sketches and highly skilled taxidermy that informed Elizabeth’s delicate paintings. Their commercial premise was the pursuit and accurate representation of the natural world.

It is noteworthy that Elizabeth wrote of ‘our’ contemplated work. While much has been made of John’s use of his wife’s talents, and his purported failure to promote her name, this was consistent with the habit of their times and not a direct indicator of his love or respect (or lack thereof). Elizabeth saw their combined efforts as a scientific and business venture which would provide financial security for their family. In fact, she had earlier complained to her mother about her ‘wretchedly dull’ existence as a governess. How unsurprising then that Elizabeth embraced the opportunity of a life with a self-made man whose curiosity, ambition and entrepreneurship would necessarily expand her own.

As Elizabeth wrote to her mother on 8 October 1838, ‘Indeed, John is so enthusiastic that one cannot be with him without catching some of his zeal in the cause, and I cannot regret our coming though looking anxiously forward to our return.’

Elizabeth died of puerperal fever after the birth of her eighth child, in August 1841. She was just 37. John maintained his passion for natural history and the family business until his death, but never remarried.

I am convinced of John’s sincerity when he wrote the introduction to The Birds of Australia, Volume 3, 1848, with the inclusion of a dedication to Elizabeth in the form of the Amadina gouldiae (now Chloebia gouldiae) – or Gouldian finch – named for her.

‘It is therefore with feelings of no ordinary nature that I venture to dedicate this new and lovely bird to the memory of her, who in addition to being a most affectionate wife, for a number of years laboured so hard and so zealously assisted me with her pencil in my various works, but who, after having made a circuit of the globe with me, and braved many dangers with a courage only equalled by her virtues, and while cheerfully engaged in illustrating the present work, was by the Divine will of her Maker suddenly called from this to a better and brighter world; and I feel assured that in dedicating this bird to the memory of Mrs Gould, I shall have the sanction of all who were personally acquainted with her, as well as of those who only knew her by her delicate works as an artist.’

The cockatiel and the finch beckon me back to another truth associated with the Goulds where there was, emphatically, no evidence of consent: the British colonisation of land which belonged to others.

John’s expeditions in Australia were often informed by Aboriginal guides. Eliza remembered, ‘Father was necessarily out most of the time exploring and I have heard him speak of the blacks he had with him, especially of one with his wife Jennie and of the convicts Government allotted to him to explore’. The Goulds saw no paradox in their ready acknowledgement of the pre-existent knowledge of country, flora and fauna of their Aboriginal guides. Indeed, there was a further irony; John warned of the danger to native species of birds and animals if unfettered colonial settlement was allowed to destroy their natural habit. They were prophetic words – the previous population of hundreds of thousands of Gouldian finches has now been reduced to small colonies.

There was another incursion: Elizabeth’s brothers, Charles and Stephen Coxen, were early settlers to Australia; while on a four-month expedition seeking specimens of birds and mammals for the Goulds, and travelling in sparsely settled country between the Hunter and Namoi Rivers in NSW, they took a five-year-old Gamilaraay boy, John Bungaree (1829–1855). It is unclear how and why they did this, and I am yet to find out. It is possible they found him after his family had been forcibly dispersed by them or others. The Sydney Gazette (18 April 1835) reported that the area was densely inhabited with hostile Aborigines: ‘Although Mr Coxen had some tame blacks with him, he could not communicate with these people’.

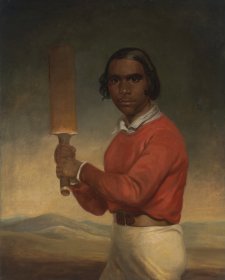

Stephen Coxen ‘adopted’ Bungaree and educated him at the Normal Institution in Sydney, alongside his own son. John Bungaree became a nineteenth-century exemplar of Aboriginal assimilation. George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector of Aborigines in Port Phillip District, wrote in his journal in 1838: ‘Visited the normal school in Hyde Park. Saw an aboriginal native youth drawing. He had, the master reported, made great advance in education, could read and write and had a taste for drawing.’

Elizabeth’s friend Lady Franklin went in 1839 to meet the prize-winning student. As The Australian noted, ‘It must not be supposed that the prize thus awarded was given in courtesy to his nation. It was fairly won from his class fellows by his ability in writing, geography and English grammar – more particularly the latter!’ The following year The Sydney Gazette followed up with, ‘It is astonishing to state that the aboriginal native lad, John Bungaree, acquitted himself much superior to the other boys of his age.’

Bungaree’s life was further fractured when Stephen Coxen, bankrupted by drought and severe flood, took his own life. Aged fifteen, Bungaree was then employed on Charles Coxen’s property on the Darling Downs; and at twenty-three he was strongly encouraged to join the Corps of Native Police on the colonial frontiers of Queensland.

Keith Vincent Smith’s 2011 piece on Bungaree in The Dictionary of Sydney states: ‘In January 1854 Sergeant John Bungaree and two Aboriginal troopers were sent to blaze trees marking the route of the mail run from Traylan … to Gladstone. Aborigines attacked the three men as they slept in camp and Bungaree was clubbed with a nulla nulla.’ Bungaree would die seven months later from a lung infection, having expressed his wish that he had never been taken out of the bush, as he had been left irretrievably trapped between two cultures.

I say sorry for this terrible violation of him, his family and his nation. Unlike Elizabeth I do not have a portrait of Bungaree to scrutinise, but I am researching to bring him into full focus alongside my family portraits. Perhaps it is inevitable that delving into the recesses of family histories will uncover uncomfortable truths. When they emerge, the very least we can do is to present them with honesty and accountability, so that both light and shadow are in full view.

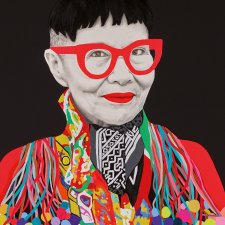

Hugh Ramsay, the fashion of Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson, Peter Wegner's centenarian series, John and Elizabeth Gould's family connections, Karen Quinlan's top five portraits and more.

Stephen Valambras Graham traverses the intriguing socio-political terrain behind two iconic First Nations portraits of the 1850s.

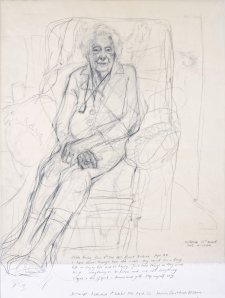

Penelope Grist discovers the rich narratives in Peter Wegner’s series of centenarian portraits.