Jim Cobb dips his finger into a swirling vat of vivid orange paint and watches as it forms a tear-shaped droplet. State-of-the-art machinery is blending pigments, resins, binders, plasticisers and other components into an aqueous, monochromatic slurry. But recognising the precise point at which the paint is the right quality still relies on human intuition. For this particular batch of artist’s acrylic, the droplet should fall off leaving a conical mark on the finger. Before it is packaged into tubes, Cobb takes a brush and smears the paint on a piece of paper or a canvas. ‘An artist paints with a brush; there’s no testing instrument that can replicate how a paint will behave when applied to a surface like that’, he explains.

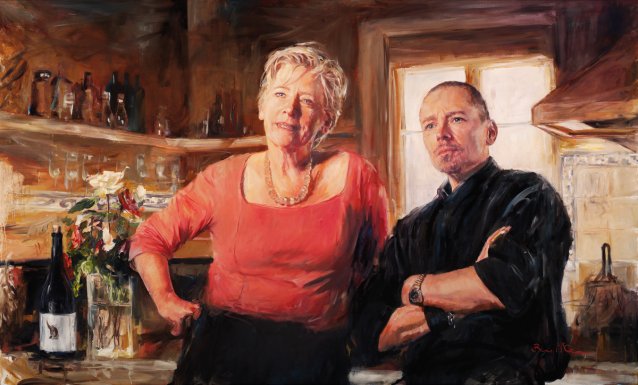

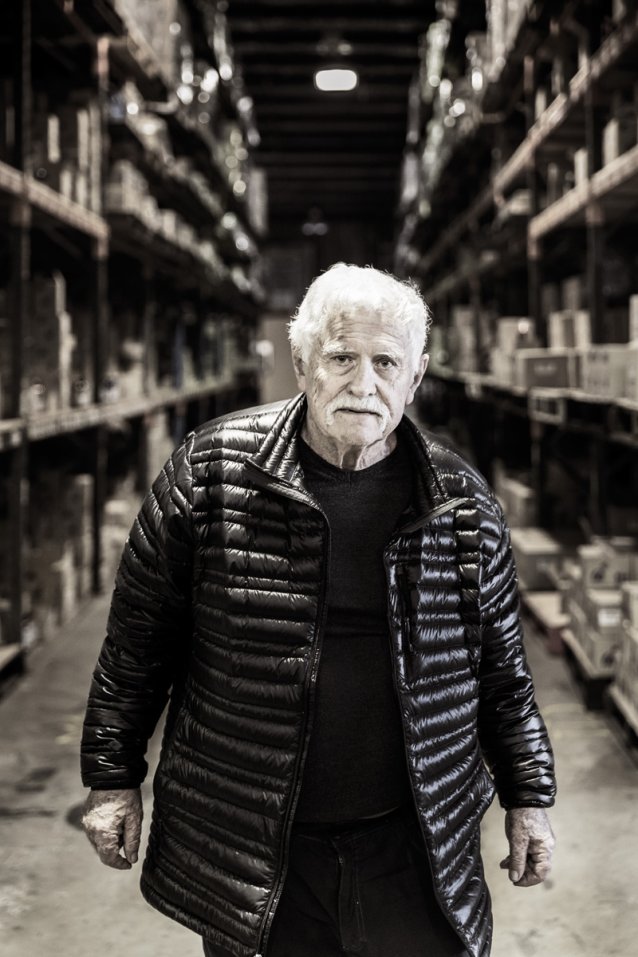

Now in his mid-80s, Cobb has been making artist paints for longer than anyone else in Australia. He set up his first workshop in Sydney’s Kings Cross in 1965, scouring nearby chemical factories to get the material he needed to produce acrylics. Today his Chroma factory at Mount Kuring-Gai on Sydney’s northern outskirts employs more than two dozen people. A second factory in Pennsylvania services the American and European markets. His long association with the raw ingredients that are fundamental to transforming a blank canvas into a finished work of art has made him somewhat of a legend in Australian art circles. Not only has he been a paint-maker, he has also mentored and supported a generation of emerging artists. ‘He’s more like an artist than a scientist’, says Sydney painter Euan Macleod. ‘There is this desire in him to play and have fun.’