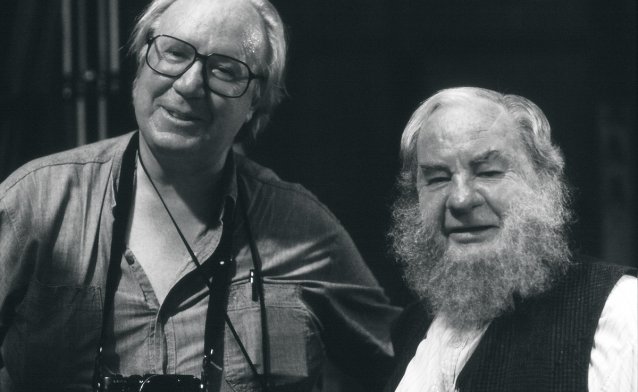

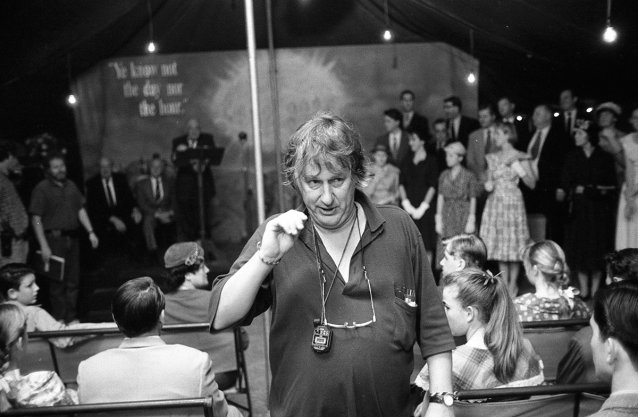

‘I never thought of myself as a stills photographer per se’, reflects Robert McFarlane. ‘I thought of myself as a documentary photographer who had been hired to document the production.’ Over the phone from his home in Hallett Cove in Adelaide’s south, McFarlane spoke with me about his experiences as unit stills photographer on numerous film and television productions, including Sirens, The Year My Voice Broke and Muriel’s Wedding. It was a delightful exchange; he skipped through various anecdotes and was full of warmth and affection for his subjects. He also provided fascinating insights into the ambiguous and beguiling quality of on-set stills – a sub-genre of portraiture that lies somewhere between documentary photography, photojournalism, art and publicity.

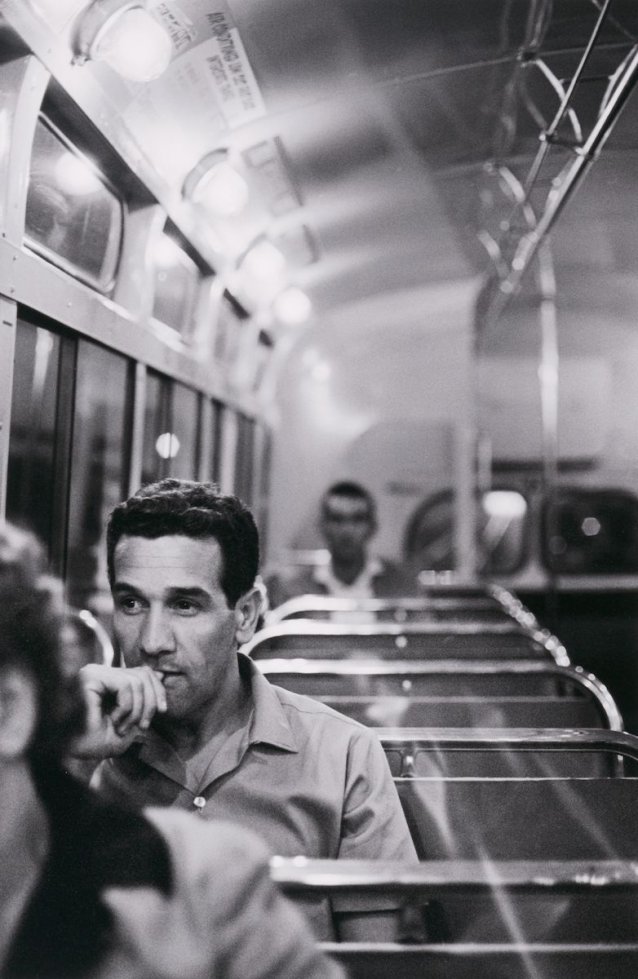

Born in 1942 and raised in Brighton, South Australia, McFarlane moved to Sydney in 1963, aged twenty-one, to begin a career as a documentary photographer that has now spanned over fifty years. Working as a freelance photojournalist in that city, his pictures appeared in The Bulletin, Vogue Australia and Walkabout. In 1965 he heard that British director Michael Powell was filming They’re a Weird Mob at Bondi, and went down to take some portraits. ‘As a documentary photographer,’ McFarlane recalls, ‘I immediately had as much of an interest in the action behind the scenes as before the camera.’

In his early twenties, McFarlane began editing Camera World magazine; he continued writing on photography in the ensuing decades, including for many years in his role as a reviewer for the Sydney Morning Herald. In his critical writing, McFarlane shies away from sentimentality, expressing admiration for integrity and dignity in photography. As a photographer, he is prolific, with humanity, compassion and an acute consciousness of social issues pervading his practice. McFarlane himself has become the subject recently, with his life achievements as a photographer recognised in Mira Sulio’s documentary about his life, The Still Point, currently in production.

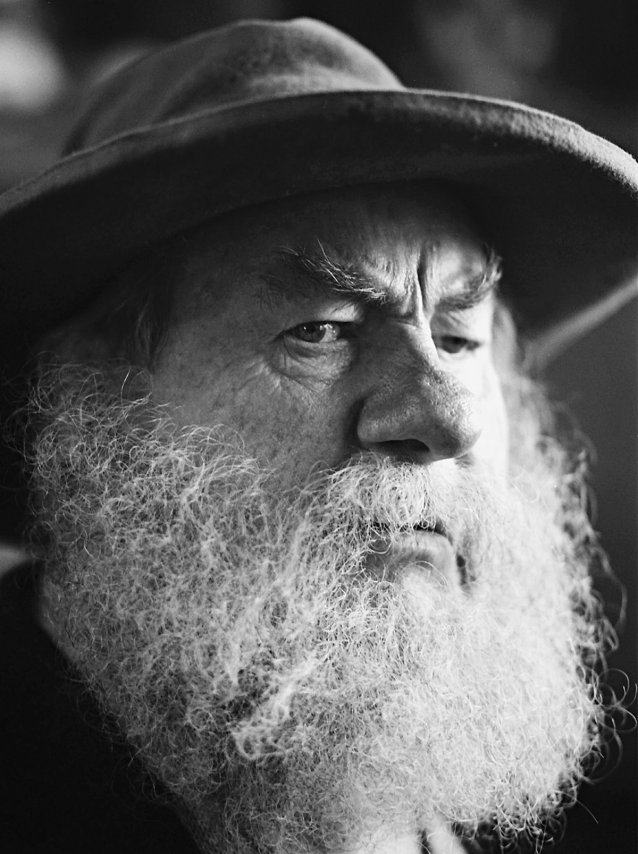

Early in our conversation, McFarlane mentions the significance of film producer Frank Taylor’s invitation to nine of the best-known photographers of the Magnum Photos agency – including Henri Cartier-Bresson – to visit the Nevada Desert location of John Huston’s The Misfits, in 1960. ‘Their response was to photograph what they found – not fabricate predictable publicity pictures’, McFarlane wrote in a 2007 cover story for Good Weekend. He noted that the photographers’ portraits of actors Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery Clift, and Clark Gable ‘brought an independent vision, and, above all, sensitivity to covering the making of Huston’s enduring, elegiac film.’ McFarlane tells me that although the Magnum photographic style is not exactly his own, the intimacy of their imagery and their belief in photographers as compassionate observers exerted a significant influence. They were, McFarlane notes, ‘certainly part of a tradition that I respect, because they tried to capture the essence of what the film was about’.