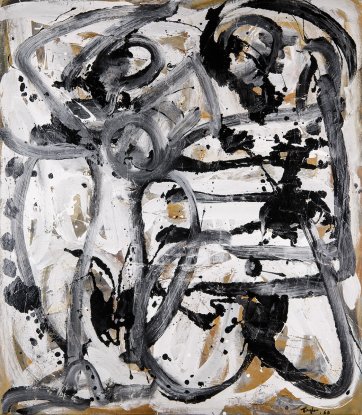

Michael Taylor is considered one of Australia’s most important expressionist painters. A master of paint, his control of the medium and his fastidious layering convey a sense of effortlessness, belying the skill involved. His technique, admired by art historians and critics across Australia, is reason enough to become immersed in the Canberra Museum and Gallery’s (CMAG) current exhibition, Michael Taylor: A Survey, 1963-2016. And yet, further to this central facet, the exhibition also reveals a great deal about the artist himself.

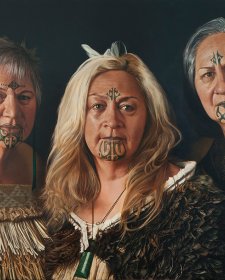

Former National Portrait Gallery Director, Andrew Sayers, once noted: ‘National portrait galleries have been traditionally predicated on the idea that identity can be equated with individuality. In Australia, however, we have Indigenous traditions in which identity is actually lodged somewhere else – in relationships and in people’s relationships to land. One could do a very interesting exhibition called “Landscape as Portrait” in the Australian context. The idea would be that there is an emphatic relationship to the landscape, which makes landscapes embodiments, signs or projections of identity.’

Sayers’ observations can be drawn upon to contextualise Michael Taylor’s works. Taylor’s creative process is intrinsically linked with his individual experiences, and every painting springs from his environment – whether through inspiration gained during one of his long walks with his wife Rominie, from the countryside surrounding their home, from drives down long country highways, or on the many trips back to the sea at the south coast. Taylor’s ability to so effectively convey the heat; the tinder-dry grasslands; the reddish earth trapped by the intense blue sky of the Monaro plains; the multifarious moods of the sea; or the inherently Australian coastal scrub and mangrove swamps, only comes with years of detailed attention to, and complete absorption in, his surroundings. It is the intimacy, then, of Taylor’s work that means it can be considered ‘landscape as self-portrait’.

Growing up on the Lane Cove River was a formative element of Taylor’s childhood; it created a fundamental bond with the sea that remains in evidence in his seascapes. His father was a very keen swimmer and would spend hours in the water. Taylor himself began swimming at age five and grew up playing in and around the river: ‘We swam when it was raining. I can remember swimming in the rain and swimming in underneath nasturtium leaves and seeing the bundles of water held in the leaves – I must have been very young – but they had a silvery quality and something about the leaf of a nasturtium used to keep them in a very tight ball.’