A monochrome photograph fixed within a large and fragile old album shows a Melanesian girl of nine or ten peeking merrily over the shell of a giant turtle. The warmth between photographer and subject is palpable. A caption, typed on a slip of paper, has been carefully gummed underneath. It reads ‘Matepai trying to imagine she is a turtle’. The tone is chatty; the child is granted the ‘dignity of naming’; the words display an engagement with the inner life of the subject.

This is one of hundreds of remarkable images taken by a Roman Catholic Marist missionary, Father Emmet McHardy, a young New Zealander stationed on Bougainville, in what was then the North Solomons, between 1929 and 1932. Emmet, together with his brother John, who remained in New Zealand, engaged in a joint venture under challenging conditions. Between them they produced a photograph album which rapidly evolved into a public presentation of glass lantern slides toured on both sides of the Tasman.

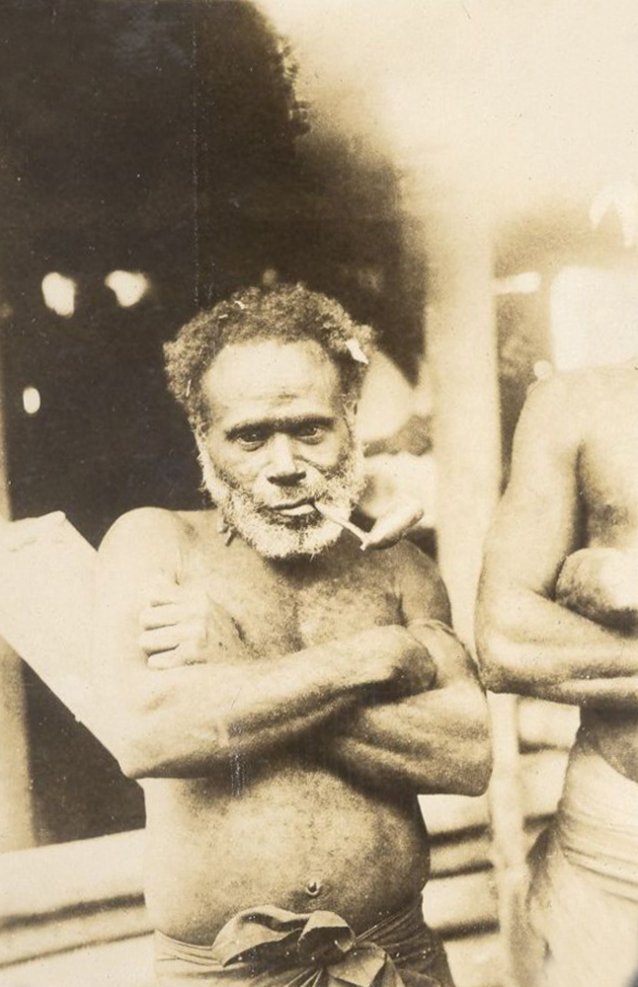

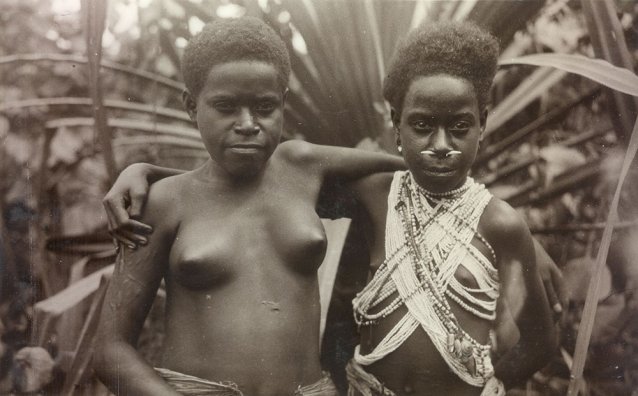

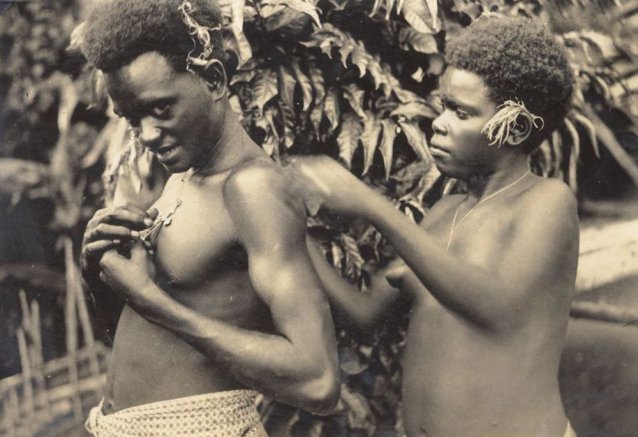

The colonial period engendered a hungry international traffic in photographs and footage of Pacific peoples. Images circulated in the West amongst ethnographers sharing information, adventurers seeking commercial gain, and Christian missionaries appealing for financial support. These categories were porous; images drifted and captions metamorphosed according to context. Nevertheless, such images were often how Europeans of the colonial period – whether from magazines, lantern slide presentations or church newsletters – gained their impressions of brown ‘otherness’.

Pictures of indigenous people taken by Western photographers ‘in the field’ were considered as documentary rather than portraiture. The majority do not meet art historian John Gere’s criteria for the latter: a representation of a person ‘in which the artist is engaged with the personality of his sitter and is preoccupied with his or her characterisation as an individual’. Disparities of power and the racialist ideology of the period made such cross-cultural, humanist engagement unlikely.

For example, consider a ‘Lantern Lecture’ circulated by the Bougainville Roman Catholic mission around 1929: the surviving typescript commentary lists sixty-two slides, although the slides themselves are missing. Excerpts from the script demonstrate the persistent seepage into missionary discourse of the ‘cannibal-headhunter’ trope ubiquitous to the adventure genre. Titles such as ‘A Fleet of the Head-Hunters’, ‘Head of a War-Canoe’, ‘Taboo House of the Head-Hunters’ suggest stock Solomon Islands popular travelogue imagery. But the more religious accent is equally sensationalist. One slide is entitled ‘A Pagan Trinity’. It carries the caption: ‘Here the devil remains very strong … there reigns here the threefold tyranny, here represented, of superstition, distrust and revenge.’