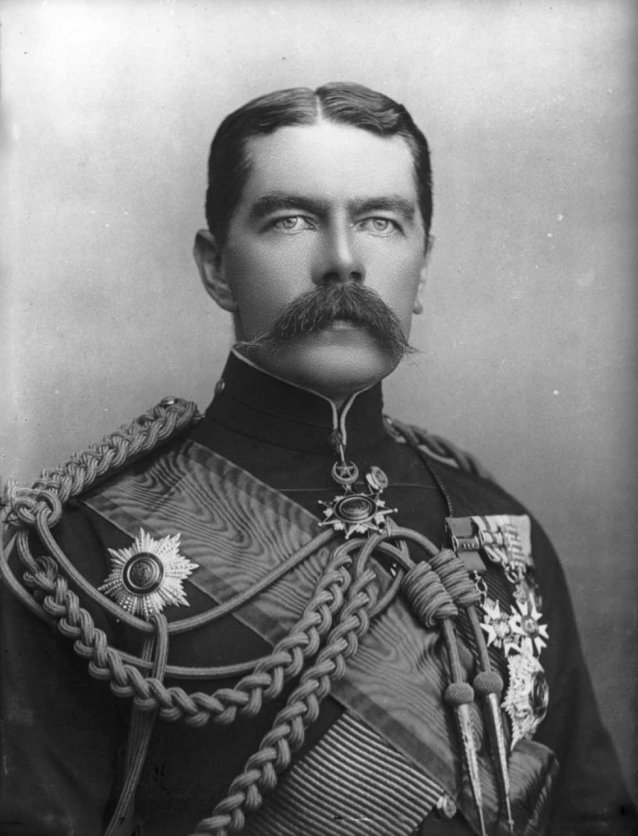

At the end of 1899, K was called to the South African (Boer) war, to act as chief of staff to Lord Roberts; he spent 1900 organising rail systems and securing supply lines. In November that year Kitchener became commander-in-chief. William Birdwood was amongst his trusted staff, who were often referred to as ‘Kitchener’s boys’. Ruthlessly, through 1901 and early 1902, Kitchener carried out a series of drives to round up Boer guerrillas, wiping out their support networks by razing their farms, killing their animals and collecting their families and supporters into ‘concentration camps’ (it was the first use of this term). In the camps, starvation and disease prevailed; the late historian Sir Martin Gilbert, who was no sensationalist, puts the fatalities at 28,000 Boer women and children,

and 50,000 Africans.

About 16,000 Australians fought in the Boer war, and as many died of disease as through battle. At the end of February 1902, as the third, dirty phase of the conflict was coming to a close, ‘Breaker’ Morant and his friend Peter Handcock (who were, at that time, not part of an Australian force, but members of a British irregular unit called the Bushveldt Carbineers) were court-martialled and shot for murdering Boer prisoners and a German missionary. Although they didn’t deny killing their charges, they claimed that orders had come from the top – and the top was Kitchener – to ‘take no prisoners’. He makes a rigid yet sly villain in Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant, but there is no direct primary evidence that Kitchener gave the order to take no prisoners. Nor is it certain that he ordered their punishment to make an example of Morant and Handcock, curry favour with the Boers with whom he was attempting to negotiate a peace, appease the Germans, or provide a ‘firm but fair’ counterpoint to his own pitiless modus operandi with the Boers.

Whatever Kitchener’s matrix of motives, the War Office statement, published in the London Times about five weeks after the executions, made no mention of any claim by Morant concerning instructions from up the line, nor of the defendants’ having been called to arms to help quell a Boer attack in Pietersburg while awaiting trial (which may have entitled them to ‘condonation’ under military law). Australians who persist in regarding ‘the Breaker’ as a hero or victim, and/or those who believe that the trial was shabbily conducted, bear an inextinguishable grudge against Kitchener for signing their warrants of execution, and also, just for being a stiff snob. By May 1902, Kitchener had punished the Boers – and then negotiated with them – to the extent that their leaders were prepared to sign the Treaty of Vereeniging in Pretoria.

After his South African success, K became Commander-in-Chief of Army in India (where Birdwood served with him again). There, he set about consolidating the country’s many large armies into one – all the time, personally, hoping to succeed Lord Curzon, who disliked him, as viceroy. At the end of his Indian period in mid-1909, the Australian prime minister Alfred Deakin cabled Kitchener, asking him to come to Australia to advise on laying down the foundations of a new national land defence system. As it happened, K was in need of a break; he replied to Deakin ‘I will be glad of this opportunity of meeting again men who served so well under me in South Africa, and to help ... with any advice I can give’.

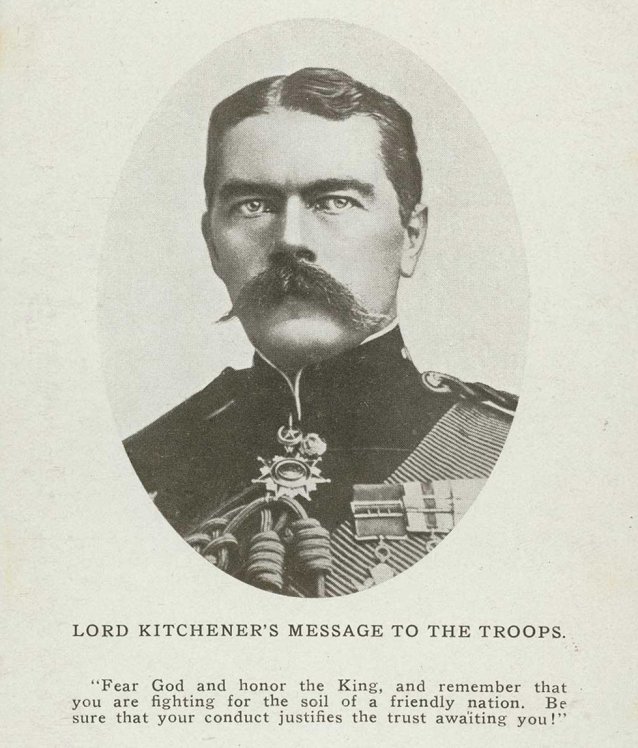

Field Marshal Lord Kitchener arrived in Darwin four days before Christmas 1909. Travelling with him at the public’s expense was his companion, Captain Oswald FitzGerald of the 18th Bengal Lancers. The men had met in 1907, and from that time, according to biographer Philip Magnus, ‘Kitchener never looked elsewhere, and their intimate association was happy and fortunate. FitzGerald, like Kitchener, was a bachelor and a natural celibate.’ Claiming to have sensed imperial ambitions in Japan – where, as in China, he had filled many trunks with ceramics, paying for many of them himself – Kitchener found Darwin’s harbour promising, but its defences and communications wanting. Proceeding via Townsville, he was received with rapture in Brisbane on New Year’s Day. On January 4th he journeyed to Newcastle and evaluated Fort Scratchley, conducting himself with the reserve and taciturnity that was noted wherever he went; the local paper reported that ‘as cheer after cheer went up he remained perfectly composed, and but for the raising of his hat in response to the demonstration of welcome, might have been absolutely unconscious that he was the object of admiration and eulogy on all sides.’ On 5 January he took the train to Sydney. At Bathurst five days later, he unveiled a memorial to men lost in the Boer War. He was in Melbourne for a full week from the 11th; on 20 January he had a few hours in Adelaide, greeting old soldiers and taking afternoon tea at the Adelaide Club before departing on the Mooltan for Fremantle, where he arrived four days later. In Bunbury, he was presented with three trays of locally grown fruit; soon after, the Agricultural Society received his letter of thanks and congratulations. Meanwhile, Perth’s Western Mail wrote

‘The people of the Commonwealth are awakening to a real consciousness of their defencelessness and of the tempting prize their country offers ... The creator of army, a very marvel of organising genius, a sternly practical soldier of most exalted rank, comes along at the psychological moment, ready and willing to study our defence problem ... [and is] hailed everywhere with jubilation.’

Having spoken in favour of a ‘systematic, statesmanlike and comprehensive’ policy of railway extension throughout Australia – and, when pressed, having declared the Perth cadets to be ‘fine little chaps’ – the colossus of empire sailed from Albany on 29 January, carrying away a gift of Indigenous Australian weapons and apparel from the Museum. Less than a week later, he was to depart Melbourne for Tasmania; on 12 February, having returned to Melbourne, he departed for New Zealand. To a friend, he wrote that the most exhausting aspect of touring was the attention he received from local dignitaries; indeed, in Dunedin, the Mayor punched the prime minister, Joseph Ward, in the jaw, and shouldered him aside to take his seat next to Kitchener in a carriage (Kitchener, it was reported, didn’t blink an eyelid during the jealous exchange).

Notwithstanding his incredible schedule of travel by almost every kind of vehicle that had yet been invented, Kitchener wrote his forty-five page report while he was on the move, and by the third week of February parts of its contents were being reported in Australian papers. In essence, the Kitchener Report took the Defence Act as its base, but presented a workable, practical scheme for compulsory part-time training for all males between the ages of twelve and twenty-five, which would lay the foundation for a standing army of 80,000 men for defence and a mobile striking force. About half the report was taken up with detailed instructions for the organisation of martial units around the country, and most of the rest set out a firm structure for the military college that had been proposed in the successive iterations of the Defence Act. In addition, commenting that Australian railways, in their current form, would be more favourable to an invading enemy than to the defence of the country itself, Kitchener strongly recommended the formation of a war railway council. In parliament, Deakin announced that Kitchener, having organised several armies already for the defence of the Empire, had knitted together the parts of the Act in a way that the government, having no pattern, could not have hoped to do.