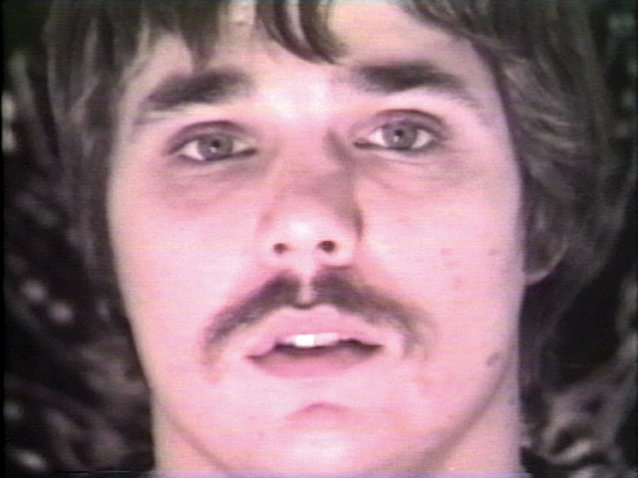

Chris was among a group of female and male students whose performance artworks were a ground-breaking force. Photographic documentation of his performances shows how boyish he appeared, like a teenager with puppy fat. 'He looks like a kid who could be kicking a ball in an empty lot' was Marion McEvoy’s description in 1975, and a commensurate air of innocence pervaded his performance artwork for the graduating students' group exhibition at University of California, Irvine in May 1971. For two weeks during the University Art Gallery's open hours, he rode a ten-speed bicycle in constant loops through the front door, out the back, around and back through the gallery again. This playful performance followed one just a week earlier where he was locked in a two-by-two-by-three-foot locker for five days.

'In some of the pieces I’m setting up situations to test my own illusions or fantasies about what happens', Chris told Avalanche magazine interviewer, Willoughby Sharp, in 1973. The five days he spent inside the locker for his Masters of Fine Art graduating presentation didn’t evoke the sense of isolation he had anticipated. Instead, Chris found himself engaged in conversations through the ventilation grilles in the closed locker door. Art professors even held classes in front of the locker, with Chris participating in the discussions. Softly spoken, Chris would grow up to be an 'amicable man', as Peter Schjeldahl put it in a 2007 New Yorker profile, a 'solidly fleshy' sixty-year-old 'given to arduous enthusiasms'.

At Market Street, in the bed, days passed. A new feeling settled upon him. Twitches in his fingers and toes softened into warm pulses. Circulatory and nervous systems hummed, muscle tissue and fat stores oscillated heaviness into weightlessness. Breath found a deep rhythm. His mind was alert, precisely tuned to the wet, warm signals washing through his body. I could stay like this, Chris thought. As the performance piece progressed, his friends became concerned, worried that he had 'flipped out'. Towards the end, Chris felt a 'sort of nostalgia' for the experience, 'a deep regret for having to return to normal', but he knew it was inevitable. After the scheduled twenty-two day exhibition, he got up and it was over.

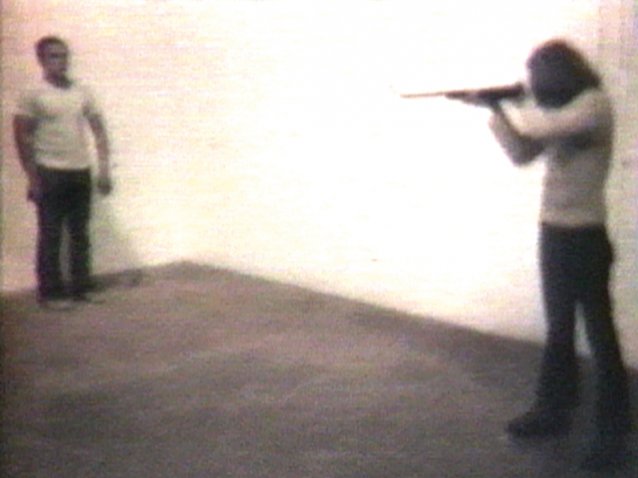

Three years later, in 1975, Chris asked for a large corner shelf to be built 'ten feet above the floor and two feet below the ceiling' for his solo exhibition at Ronald and Frayda Feldman’s gallery on New York’s Upper East Side. This time he spent twenty-two days lying flat on the shelf, out of the view of gallery visitors, subsisting on fruit juice. His thoughts and emotions echoed the experience of Bed piece. 'What's weird,' Chris said, when interviewed by David Robbins in 1980, 'is that you start to like it up there. You feel power, because nobody knows what's going on. I don’t just sit up there and meditate. I go to work, psychologically.' Chris' 'psychological work' was noteworthy. Helene Winer, who ran the gallery at Pomona College in the early seventies, recalled it as 'hyper-focused detachment'. And it was this intense detachment that Chris had needed to call upon four years earlier, for the performance piece that is regarded by many as his defining moment.