The assessment was correct in substance, but underestimated the potential of this singular young man. 'Yours is an intellect of ability, not genious' [sic], wrote Hamilton. But this tall, dark-haired person was in fact Alfred Deakin, lawyer, journalist, spiritualist, and future Prime Minister of Australia, who had consulted Hamilton under an assumed name. Deakin had already been elected to the Victorian parliamentary seat of West Bourke the previous year, but resigned in his maiden speech following claims about unfair polling. When he sat for Hamilton, his ideas and ambitions may have been in a state of turmoil. Just weeks after the phrenological reading, he would lose the election for his seat, only to regain it by July 1880.

Perhaps the phrenologist guessed the true identity of his sitter. After all, he took a keen interest in civic and political life, donating lecture proceeds to charity, running for public office, and campaigning against capital punishment. Hamilton argued that phrenology could be used to reform the characters of criminals, or applied pre-emptively to children to prevent the fulfilment of a sinister, destructive anatomy.

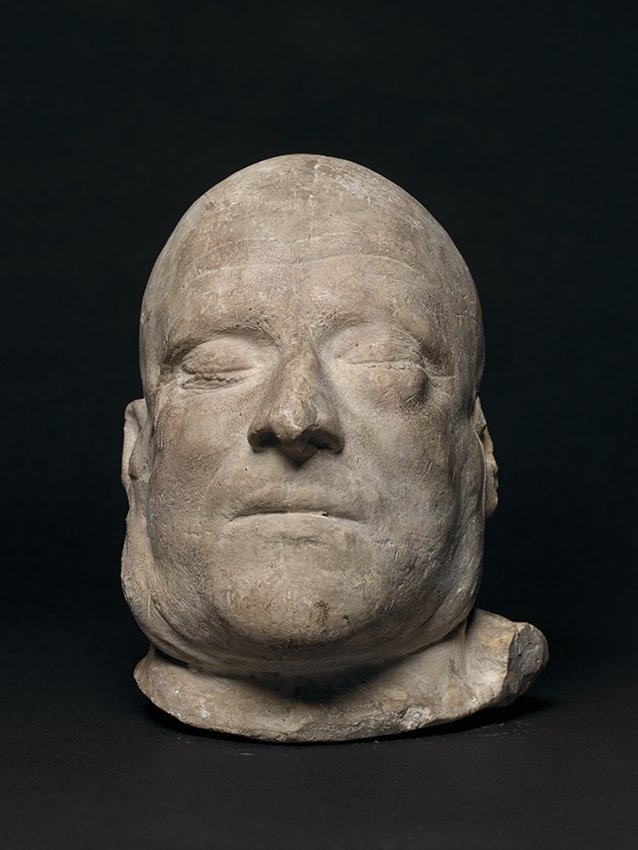

But Hamilton was not beyond moral reform himself. In his most famous transgression, in the regional centre of Maitland in 1860, he was charged with inciting to exhume corpses from a burial ground. His target in that case was the skull of the Aboriginal man Jim Crow, executed a few months earlier. Hamilton had approached the sexton of the St Peter’s Church of England Burial Ground and offered one pound if he would dig down and remove the heads of Jim Crow and the convicted murderer executed that day. Hamilton was acquitted by jury of the alleged incitement, and secretly returned at some point during the next two years to exhume the skull that was denied to him. In somewhat tangled reasoning, he used it to argue that the young Aboriginal man could not be legally culpable because of the 'moral idiocy' revealed by the skull, a judgment contradicted by a Hunter Valley local who knew Jim Crow and argued for his intelligence.

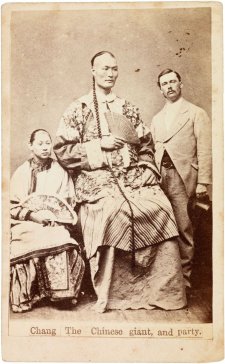

In the guise of Victorian theatricality, Hamilton’s collection of human remains was a powerful drawcard to his lectures. By the time of his death, he had amassed some 55 skulls or parts thereof – about 30 Aboriginal, four Maori, one 'Hindoo', one Chinese, and the rest European. He sourced them not only through grave-robbing, but also through gifts and trades within the networks he forged in each new town.

Three of his Tasmanian criminals were hanged and dissected, two of them at St Mary’s Hospital, a 60-bed institution for the labouring classes run by the City of Hobart’s medical officer, Dr Samuel Edward Bedford. Museum Victoria, in Melbourne, now holds the collection, and several of its non-European members, including Jim Crow, have been repatriated to country.

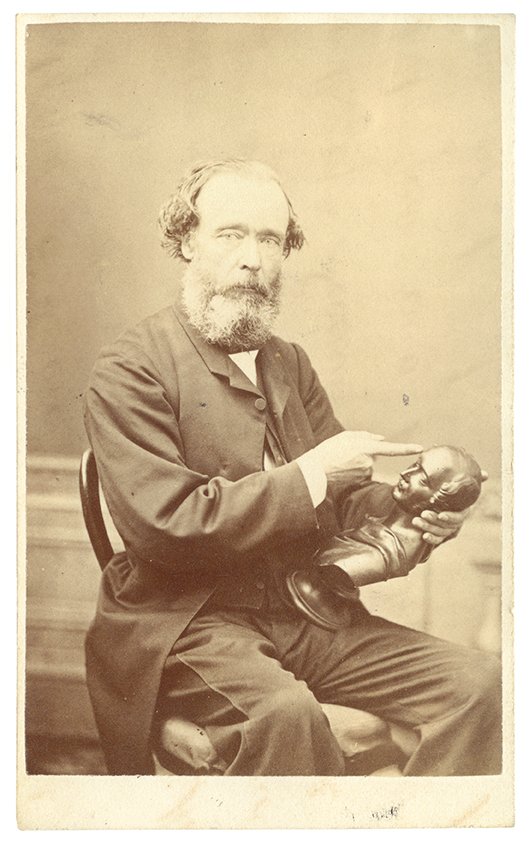

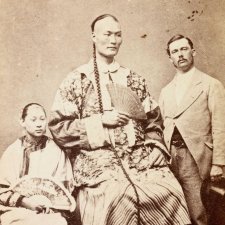

The only surviving photograph of this fervent collector (to our knowledge) is a carte de visite taken by Archibald McDonald, whose studio was based in Melbourne’s St George’s Hall, Bourke Street East, between roughly 1864 and 1873. Newspaper advertisements and articles that reveal Hamilton’s movements suggest that he did not return to Victoria until the late 1860s after a stint in New Zealand, meaning that by the time he posed for McDonald he was in his late forties. Hamilton’s wavy hair had receded so far by this stage as to truly accentuate what his third wife, Agnes Hamilton, referred to as his 'colossal forehead'. His eyes sternly meet the viewer, and in a reference to his livelihood he grasps a miniature bust of Prince Albert (who dabbled in phrenology), pointing with his other hand to the prince consort's forehead.