The domestic domain of artist Kristin Headlam is both very private and curiously accessible; anyone looking at images of her work, readily available on the internet, can peruse a side-on view of her sitting room, a corner of her studio, a full frontal of the walled back yard.

Her paintings contain other paintings, so an image such as About the House showing the artist at an easel and her partner, the poet Chris Wallace-Crabbe at the kitchen sink, also includes, on the back wall, a portrait of Headlam’s late father as an old man.

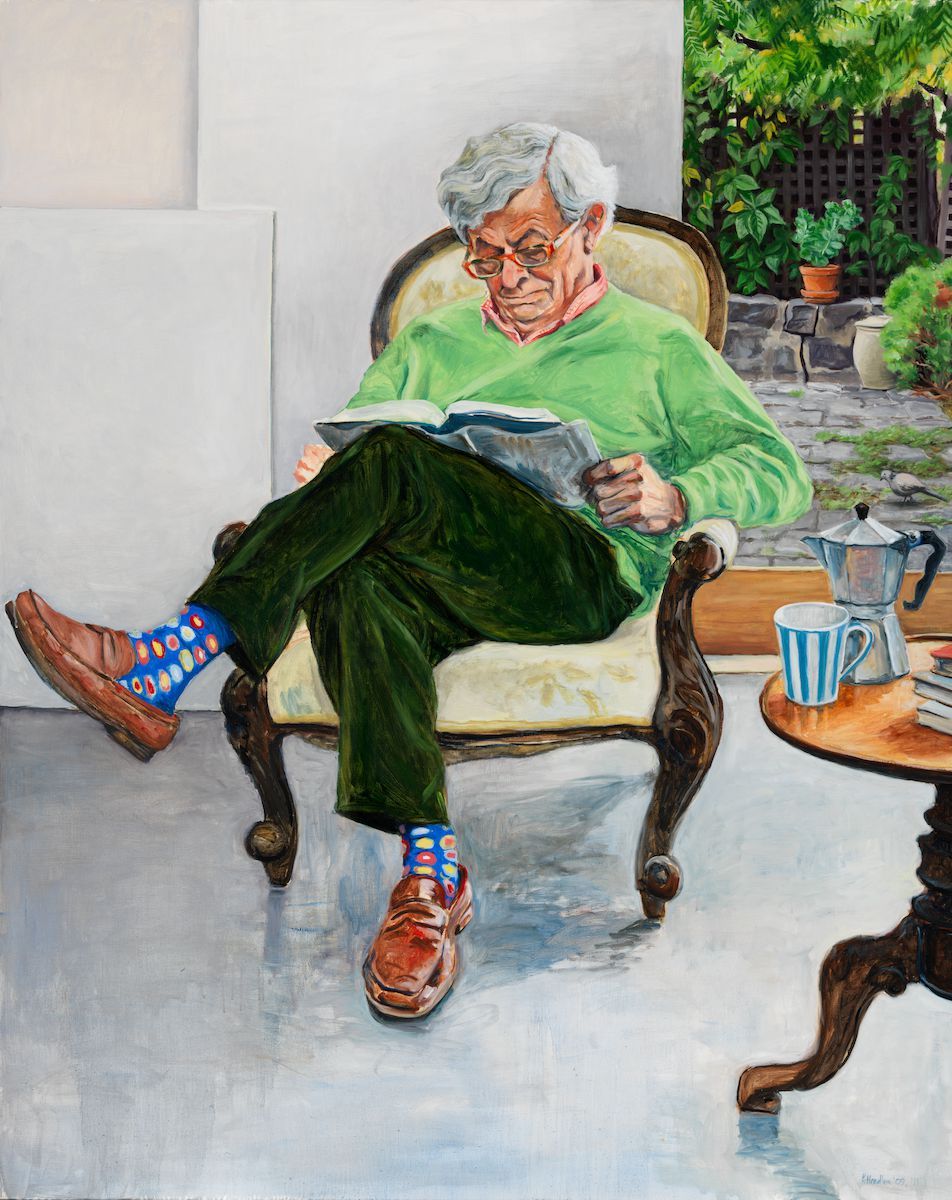

Another portrait of Wallace-Crabbe, recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, reveals her studio as stage set; she’s placed him against its interior north wall seated in an upholstered chair, a blue and white striped cup and metal coffee pot within easy reach, a book on his lap. The light streams in through a window, giving a view to lush foliage, a garden trellis and bluestone pavers. This garden is one she has painted many times; the subject’s jumper, lettuce green, is a colour I discover crops up in several garments in both their wardrobes.

On my first visit to her house in the northern suburbs of Melbourne, I therefore feel that I am entering familiar terrain. Only the dog in the painting is different; Pamphlet has died, and Basil, a red heeler cross, has taken his place on the sofa.

Headlam’s reputation as a portraitist rests on a mix of commissioned works, private explorations and prizes. The former includes a portrait of Dame Elizabeth Murdoch that hangs in the dining room of Trinity College at the University of Melbourne, and another of the distinguished research scientist Jacques Miller for the Walter and Eliza Hall institute, also at the University of Melbourne.

In 2000 she won the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, the country’s (and world’s) most lucrative portraiture award, for her painting Self Portrait in Bed with the Animals.

Animals crop up in several other group portraits; a study of her art dealer and friend Charles Nodrum with his wife, daughters and four pets and The Burns Boys with their long haired collies reveal a gently humorous sensitivity to group dynamics, and the pre-eminence of pets as familiars and envoys.

We have coffee in recognisable cups at an identifiable table. Headlam has agreed to take part in a ten-part Radio National series, “Australian Portraits,” that I am making with the NPG’s director, Angus Trumble, as co-host.

The project needs a first-hand sitter experience. Fortuitously, Headlam had already indicated that she was looking for subjects to, as she phrased it, get her eye back in, so I have put my hand up.

I’m not without trepidation. There’s something unnerving about being scrutinised; the old fashioned term, to take a portrait taps into atavistic notions of souls captured, something lost. Another worry, even though I felt myself realistic as to my middle-aged charms, was that vanity might manifest itself in unexpected ways. I realised that although I was more concerned about looking intelligent than attractive (to be honest, I hoped for that too) on that first day I took extra care with my make-up (laughable in hindsight) and the colour of my jacket in relation to my skin tone (a much smarter consideration).

As she leads me to the garden studio, Headlam says that she isn’t interested in capturing anything metaphysical. “I don’t think of the soul at all,” she says, “only what the face is doing. The soul can take care of itself.”

She also paraphrases John Singer Sargent by adding, wryly, that a portrait is a painting where there’s something wrong with the mouth.

It’s a prescient comment; many artists prefer their sitters to be quiet; Headlam likes them to talk. It makes painting the mouth particularly difficult, she concedes, but the benefits outweigh the inconvenience.

The studio is a cool white space, with a metal plan chest, several easels and a storage area upstairs, crammed with canvases (I notice a full length study of the musician and Cat Empire co-founder Felix Riebl).

Downstairs, one wall is studded with pen and ink sketches, studies for a series of 40 prints to illustrate Wallace-Crabbe’s verse novel The Universe Looks Down. Another features similar sized portraits to my own, life-sized heads against the white of the canvas. I recognise two poets: Melbourne based Lisa Gorton and the UK writer William Eaves. He wears a frown.

Whereas her larger portraits are usually full of artefacts and settings that reflect the sitter, these are stark. If you cover the whole canvas, you’re creating a complex illusion, she says, but with these studies there is no artifice; “this is a person made from paint,” she adds.

There’s a much more conversational tone to her private projects and domestic commissions, she explains. With formal ones, she doesn’t allow herself the same liberties or playfulness. She would rather work from life than from photographs and insists on spending time with even the busiest sitters. Not always, though; she mentions a portrait of the former Tasmanian premier, Harry Holgate, commissioned by the Tasmanian Parliament and painted post mortem. “They were catching up,” she comments dryly.

Headlam’s chalked crosses onto the floor to mark the legs of the chair I’m to sit on. I get a tick of approval for my muted greeny-blue jacket and scarf and am reminded of something I had read about William Dobell’s portraits of the cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein, how she kept on appearing with complete changes of clothing and sackfuls of gaudy jewels. Throughout our several sittings, I keep to the same costume.

It’s time for business. Headlam uses small, flat brushes and squeezes oil paint on to a clean glass plate in tiny daubs and in a muted range of hues –“too many colours make me nauseous.” She confesses to a weakness for yellows and titanium grey. No, she doesn’t always mix every colour from scratch. “I can’t be bothered,” she says laughing, but then adds, in a typical self-mocking way, “I feel by some measurements I’m not a real artist. But then self-doubt is a necessary part of most artists’ personality.”

A friend described having his portrait painted as akin to visiting the dentist. He had to sit still; having been invited to chat, I become a babbling stream of anecdote, and, as the sittings continue, alarmingly confessional. Headlam also chats, about politics, people, art and her own life, all in a dry, witty and self-deprecating manner. She takes her work seriously, she reveals, but not necessarily herself.

Daily life is a settled routine centred around work, with a swim in the open air Brunswickpool each morning before heading for the studio at about ten. There’s a break for lunch when she catches up with Wallace-Crabbe, and a long afternoon walk with the dog. Sometimes she plays piano duets with a friend. This is her schedule. If she is kept from her studio for too long, she says, she gets fractious.

Although portraiture is only part of her practice, she keeps returning to the face.

“Painting is a way of pinning things down” she says, and as she starts sketching my features onto the canvas, her main consideration is the way the muscles work on the face, how the shadows collect under the nose and chin, how the blues and greens work with the pinks of my face.

It’s hard to pinpoint which faces appeal and which don’t, she says. Personality plays an important role, and also what she calls solidity, sculptural values.

Wallace-Crabbe has defined Headlam’s style as novelistic, in the sense of developing a character over time. In part, she says, she agreed with his summary; in the to and fro of conversation, there is plenty of time to probe the psyche.

She reveals her own psyche too; the four years she spent working for a pair of psychoanalysts and the years of analysis that she underwent were useful, she says, for hearing her own voice at a deeper level. It also helped her overcome a fear of painting that had its roots in a fear of failure.

“I was a lousy student as I was frightened of working hard and discovering that I was only average,” she confesses.

Headlam was born in Launceston, Tasmania in 1953, the only child of an architectural draughtsman and his wife, a homemaker who had been given a place at the University of Melbourne to study architecture, but instead had married at 19 and remained frustrated, says Headlam, for the rest of her life.

An uncle, Alan Mcintyre, was a painter and a great encourager, and her ambitions were given a fillip when, at the age of eleven, she won the Brisbane Courier Mail junior art prize on the theme of “Me doing What I Like Best.”

Apparently this was swimming underwater - “I must have been lying in my teeth,” adds Headlam.

Although she’s been painting portraits since student days – she followed up a degree in Fine Arts and English at the University of Melbourne with study in painting at the Victorian College of the Arts – Headlam says she is still exploring a language of portraiture, and it’s taken her many years to discover the kind of portrait she wants to create. At the start, she says, she didn’t have a language, “a portrait voice.”

So who were her influences along the way?

She mentions Velasquez, Van Dyck, Degas, Manet, Hockney and “everyone goes through a Lucien Freud phase.”

“I was obsessed by the way he used paint, its lustre and weight, the way his heads looked like lumps of flesh.”

The artist who comes up most in conversation is the American painter, Alice Neel, whose portraits of friends, fellow artists and the famous in New York over 50 years from the 1930s are full of psychological insights and wit. These are characters, comments Headlam, who leap off the canvas as total personalities.

“You look at them and never question that it’s an accurate portrait, convincingly capturing all the neuroses and character traits.”

Later I see a portrait Headlam has painted of the writer and comedian Catherine Deveny, naked, laughing. It’s very Neel.

Headlam says her portraits are part of a practice and body of work concerned with modern history painting –“I’m the sort of artist who might have painted Napoleon on his horse”. This work is often based on media images and concerned with the interface between the private and the public, the public and the political.

She’s made works based on images of riots, raids and bombings, events that, once removed from the urgent glare of current news, assume an exaggerated distance from the present.

The Water Bearers (2003) showing lines of women in a ravaged African landscape, has a biblical quality; another series, based on photographs of brides, looks instantly dated even though the events recorded are relatively recent.

Handover (2008) was inspired by a newspaper photograph showing former prime minster John Howard and his wife Janette in a seemingly relaxed tête à tête with Kevin Rudd and his wife Therese Rein. The portrait pulses discomfort.

These strange tableaux, their staginess, and the insights they give into the theatre of power are the elements that interest her.

***

In the studio, the diffused light delays the sense of time passing. A couple of hours have passed, the portrait is taking shape. It is time to stop for the day.

I come around the easel to have a look. I’m relieved to see the eyes look intelligent behind an excellent pair of spectacles. Headlam’s been straightforward about the messy hair and chubby chin, and the mouth is in the process of becoming; I like what I see. It’s not there yet but it’s captured something of me, I feel. But who am I to judge?

Headlam is also tentatively satisfied, at least for now. She’s her harshest critic, she says, but also a quester after truth.

Sometimes she gets excited, “in a bit of a daze,” and feels she’s pinning something down, but she says that every portrait involves feeling her way.

“I want to find out how to do it, to be comfortable, but I never am,” she says; “too much certainty can lead to repetition.”

Getting it right is important, but “a little bit wrong can also be good.”

“If it speaks to you and you have expressed what that is, then you’ve achieved a form of communication.”