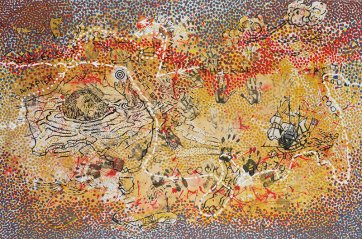

Amid the cacophony of celebration, national anniversaries give rise to reflections on nationhood and national character. In 1988, two hundred years after the First Fleet’s arrival, and again in 2001, the centenary of Federation, large scale and ambitious exhibitions of Australian art framed and toured a picture of Australian life, culture and character across the nation.

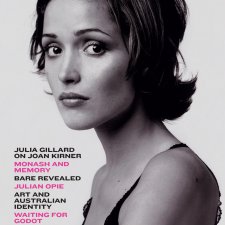

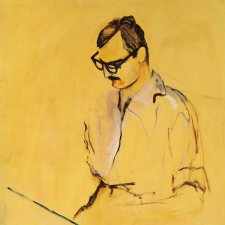

Creating Australia, 200 Years of Art 1788-1988 (curated by then Snr Curator Australian Art at the NGA, Daniel Thomas) and Federation - Australian Art and Society 1901-2001 (curated by former NGA Head of Australian Art and long-time art critic, John MacDonald) were filled with hero pictures and more modest works championing overlooked or underrepresented aspects of our society and culture. Both exhibitions cast wide nets, in particular the latter; each had inevitable gaps and the odd minnow in the mix.

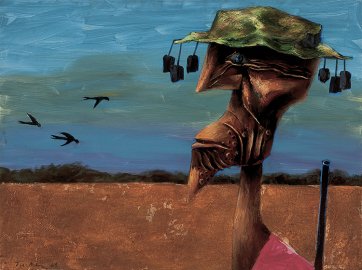

More recently, the Gallipoli centenary offered sombre contemplation on an episode indelibly inked into our history books. Despite the terrible defeat, the campaign is enshrined in our collective consciousness - with significant mythologising by early war historians, the media and film/television industries - as marking the birth of the ‘digger’, who possesses a ‘bush born’ Australian identity and character distinct from British antecedents.

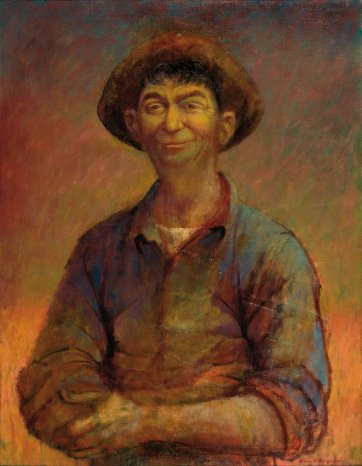

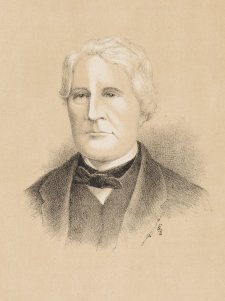

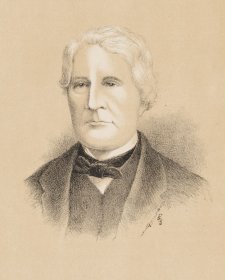

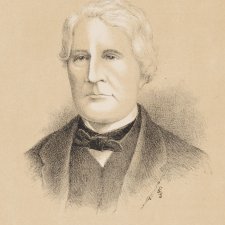

Academia offers a contradiction: in a new exhibit about colonial artist ST Gill, Professor Sasha Grishin claims Gillinvented the character of the digger with illustrations of gold prospectors in the 1860s exhibiting ‘resilience, anti-authority attitude and dry humour.’ Meanwhile, contemporary mythologising continues, with the media repeatedly describing all injured/killed soldiers as diggers; one wonders how they’ll reference the first female soldier to fall.

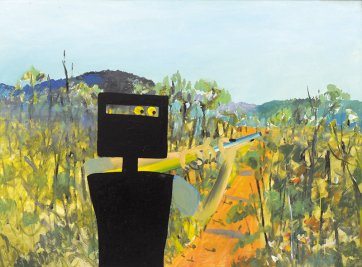

Bushranger and murderer Ned Kelly espouses the digger’s characteristics and is venerated as a cultural symbol. Sanctioned with a postage stamp in 1980 commemorating his death, his status was proclaimed to the world in the 2000 Sydney Olympics opening ceremony, where Kelly figures based on Sidney Nolan’s iconic depiction ran around the stadium ground with guns blazing fireworks.