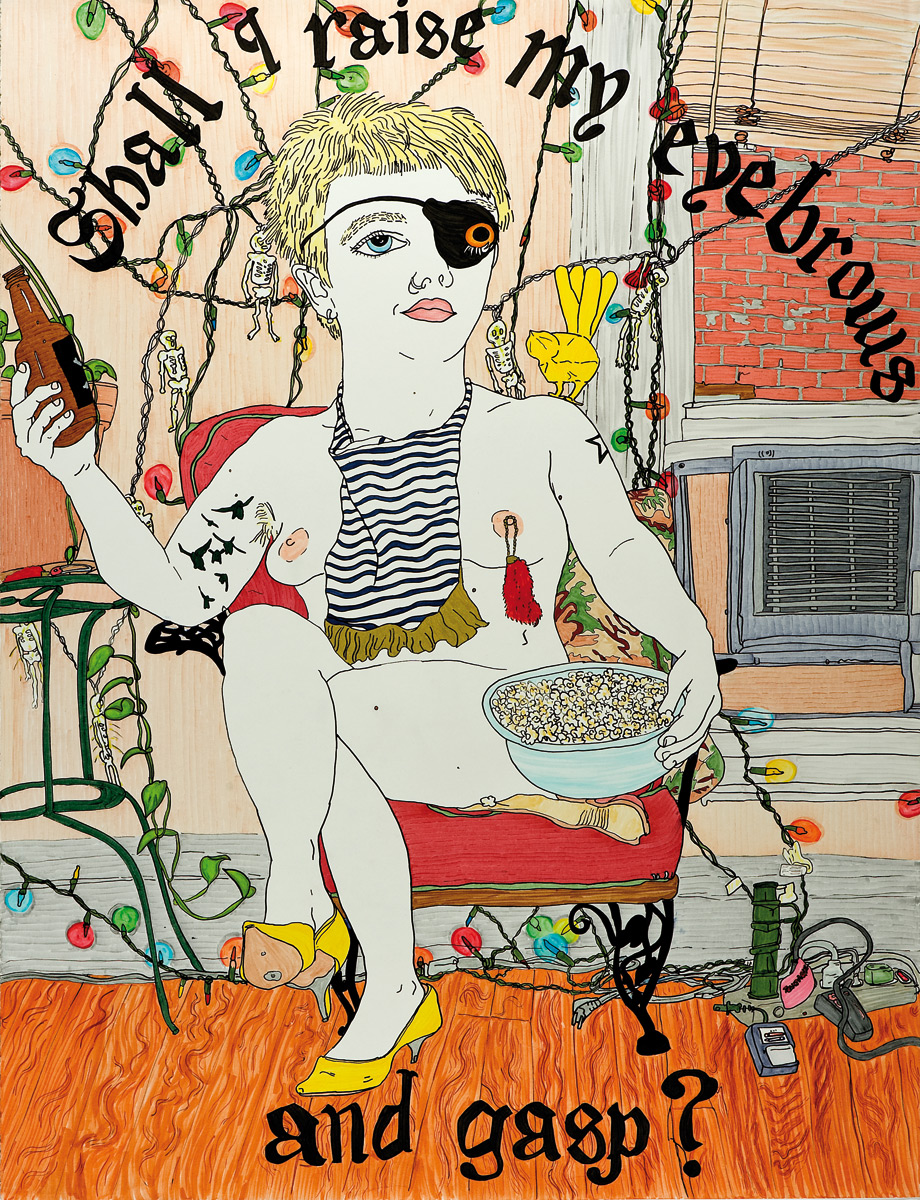

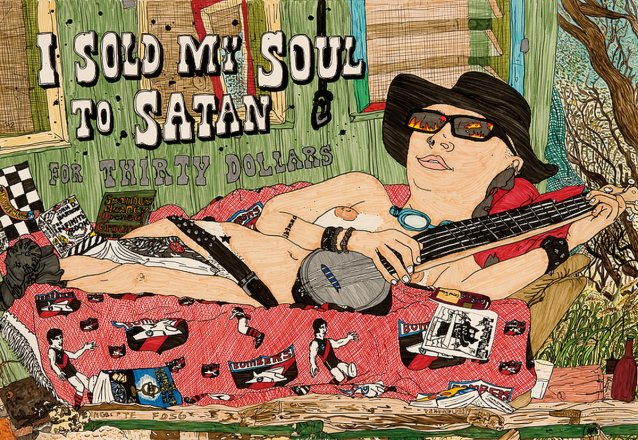

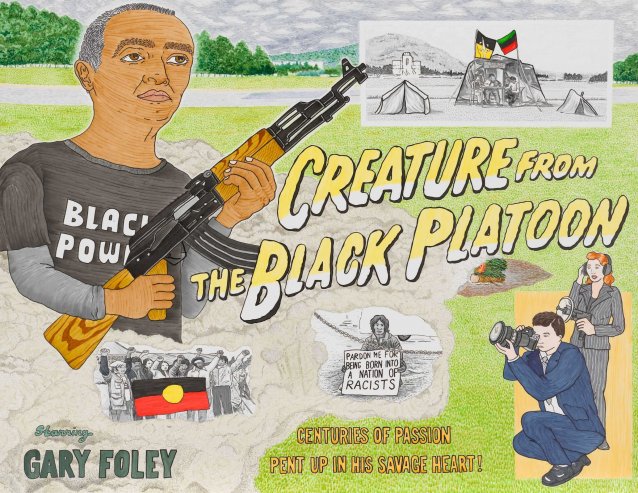

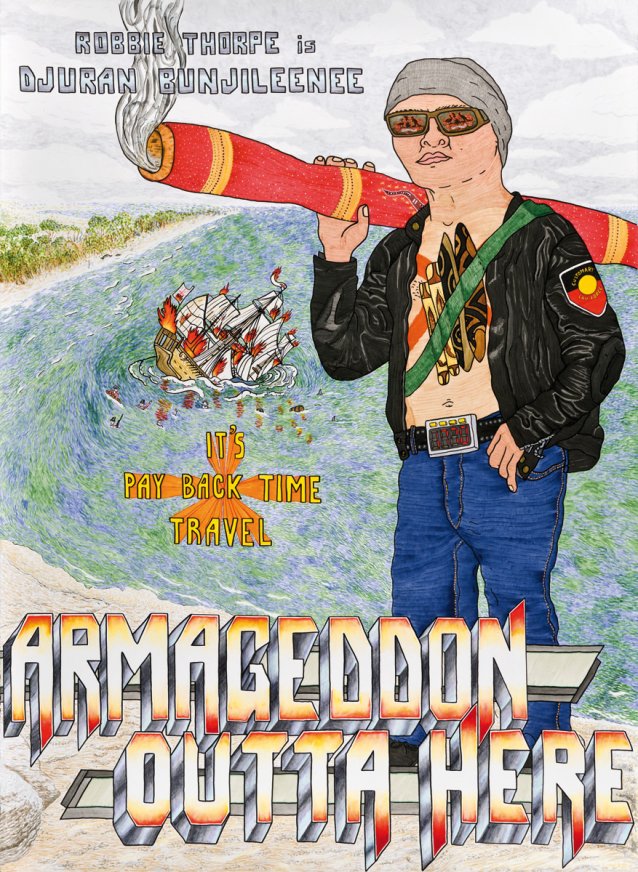

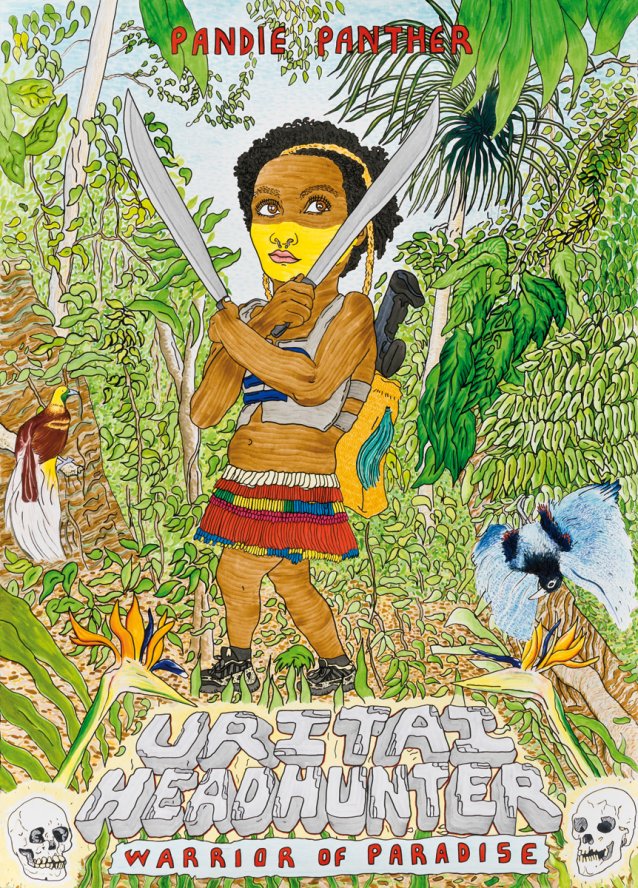

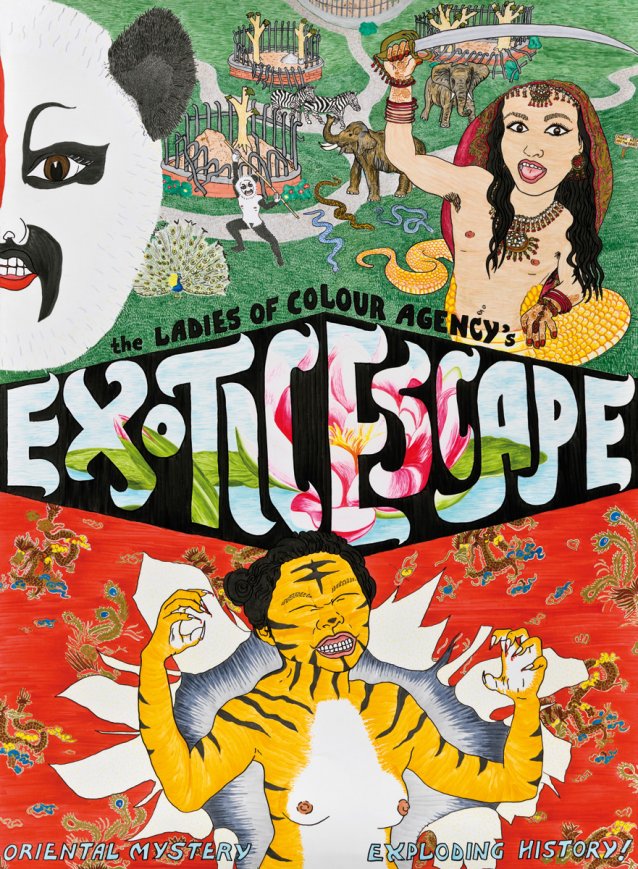

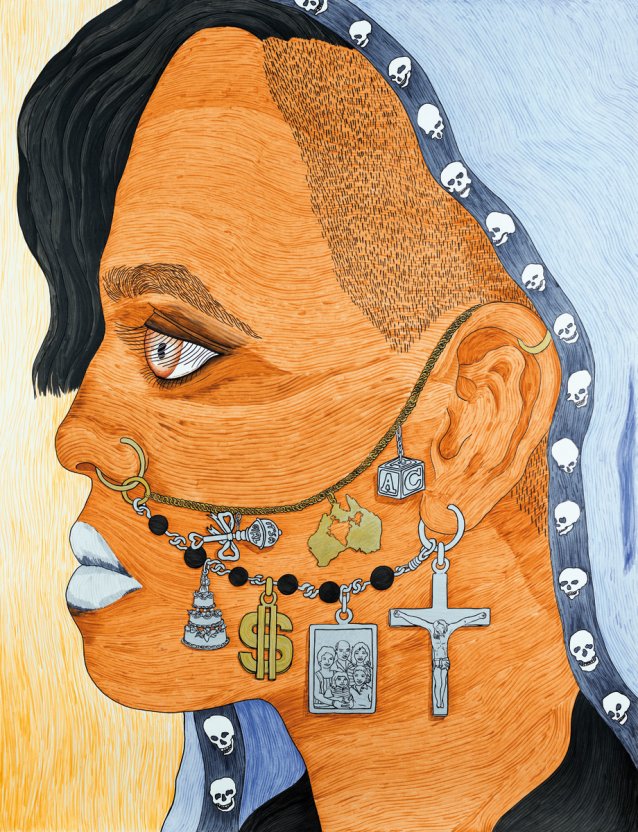

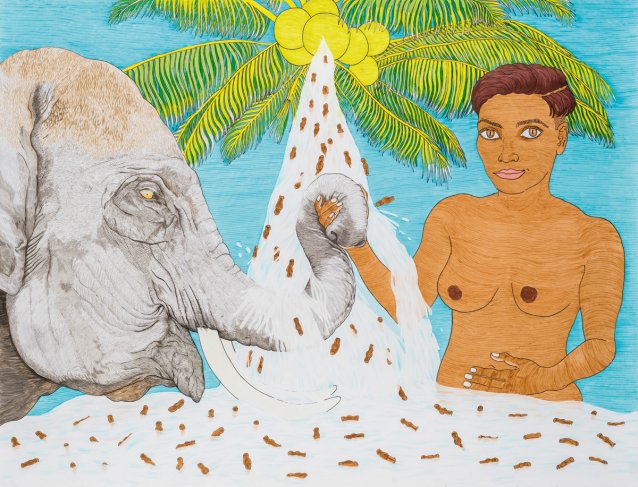

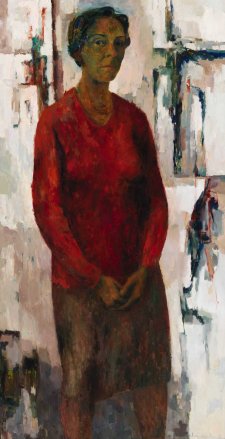

Executed in gloriously colourful felt-tip pen TextaQueen’s drawings are rich in iconography, with multi-layered meanings smartly critiquing stereotyping and socio-cultural politics.

Colouring-in is a well-loved children’s pastime, but socialisation encourages us to cast aside childish things. The parallel in art practice is drawing, which is often considered a stepping stone on the path to painting. While sculpture and other plastic arts have had a recent resurgence in the contemporary art world, non-atelier style schools are devoted to exploring other media. And so it was with TextaQueen, who ‘drew a bit’ at art school while concentrating on experimental video and photography. The focus on drawing with felt-tip pen occurred after art school largely through necessity: ‘I turned to Textas because I could get them at the supermarket and they were portable’. TextaQueen’s portraiture-based oeuvre is also unusual in contemporary art. This choice, however, was deeply personal. ‘Portraiture has been a way to connect with people. It’s part of my personality – being awkward, really socially anxious, but really sociable. In big social circumstances it’s hard to have real connections with people. Drawing people intimately is a really beautiful way of getting to know them; not that I did it for that, but it became an extension of my social relationships.’

Apart from large-scale drawings, TextaQueen’s nudes have appeared on playing cards, in collaborative animations for the National Portrait Gallery, SBS TV Australia and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, in zines, murals, postcards and calendars. They’ve been woven into a tapestry, appeared on tea towels and once on a surfboard. The works are filled with the faces of friends and ‘unique women’, many of whom are artists and activists, musicians and queer performers. These drawings, with their sitters characterised as ‘performative personalities’, are collectively described as Textanudes and have been the subject of national and international solo shows since 2001.