In the flesh is an exhibition about humanness – the experience of a mind enfleshed in a body.

It can be enlivening, unsettling, joyous and just plain weird to consider humanness. Humanness embraces humanity, human nature and the human condition. Humanness lurks at the threshold of controversial science and medicine and is invoked by history’s worst atrocities perpetrated upon those perceived as less than human. It makes one wary of words like ‘universal’, ‘fundamental’ and ‘us’. Humanness is distinct from consciousness, embracing as it does instinct, emotion and the subconscious. Relationships between the human mind, flesh and lifespan underpin the nature of portraiture.

General Reflection on Man:

It needs twenty years to lead man from the plant state in which he is within his mother's womb, and the pure animal state which is the lot of his early childhood, to the state when the maturity of the reason begins to appear. It has needed thirty centuries to learn a little about his structure. It would need eternity to learn something about his soul. It takes an instant to kill him.

Voltaire, Dictionnaire philosophique 1764

Every discipline of intellectual enquiry has struggled with the concept of humanness, not to mention most works of the imagination. Philosopher Arne Naess observed, ‘several thousand years of philosophical, psychological and social-psychological thinking has not brought us an adequate conception of the I, the ego, or the self’. A hundred years ago, Ambrose Bierce satirised this constant self-inquiry defining man as ‘an animal so lost in rapturous contemplation of what he thinks he is as to overlook what he indubitably ought to be’. A fair call.

Sixty-three works by Australian contemporary artists Jan Nelson, Natasha Bieniek, Patricia Piccinini, Juan Ford, Petrina Hicks, Ron Mueck, Yanni Floros, Sam Jinks, Michael Peck and Robin Eley are presented in ten themes: intimacy, empathy, transience, transition, vulnerability, alienation, restlessness, reflection, mortality and acceptance.

The contemporary art of In the flesh takes the weight of the thousands of years that human minds have expressed in art their struggle to comprehend the existence, transformation and demise of the human body. The ten quotations from Shakespeare to The Doors that accompany each theme reference this legacy. The striking ‘newness’ of the works are grounded within classical forms. Each artist selected for In the flesh adapts their medium and technique – photography, oil painting, drawing, sculpture and video – to the elements of humanness they embody. As Kenneth Clark observed of classical sculpture in his art historical survey The Nude: ‘This feeling, that the spirit and body are one, which is the most familiar of all Greek characteristics, manifests itself in their gift of giving to abstract ideas a sensuous, tangible and, for the most part, human form.’

There is no inherent personal story to the figures in the exhibition. The uncanny effect of the sculptural works and the photographic surface of the paintings allows for an immediate, direct and visceral engagement with the themes. The work has the constructed stillness of abstract ideas rendered tangible.

Many of the selected works have often been described as ‘hyper-real’ or ‘photo-real’. However, this is not why these works have been brought together here. Underpinning the exhibition is the question ‘what it is to be human?’ – a question all the works confront directly. This is importantly distinct from the question ‘what is real?’ For the hyper-realists, super-realists and photo-realists who emerged in the mid-1960s and 1970s, artificial realism itself was the point. They explored and critiqued the indeterminacy of the image, value, truth and perception in contemporary life. Verisimilitude in In the flesh serves a different purpose – a very traditional one – the realness represents the themes of humanness.

Inquiring into the self and identity lies at the heart of our purpose as a portrait gallery. Always in my mind while developing the exhibition was how the experience of might alter an experience of the National Portrait Gallery’s permanent collection of Australian portraiture. For me, it has meant a heightened awareness of the fall of the subjects’ skin and the shape of ears and finding my mind turning to how subjects’ might have felt in their teens or whether their hands shook while speaking publicly. How the bodies and minds intersect crowd into my mind as a thousand details. Experiencing the contemporary art within this exhibition is a reminder that all portraiture is embedded in the flesh and a life’s biography is found in its humanness.

Intimacy

In experiencing intimacy the human mind wrestles with the impossible task of being as one with another. Sculptor Sam Jinks unites the textures of the human body and human emotion in these works addressing moments of intimacy. Jinks observed the ‘form and texture of frogs and frog-skin being very similar to babies and baby skin’ and formally arranged this vision of the touch in Small Things. The symmetry and almost-touch of Unsettled Dogs takes on an allegorical dimension: the dog-headed cynocephalus of ancient and medieval imagination reminding of the human capacity for destructive irrationality within intimate relationships.

It is not time or opportunity that is to determine intimacy;

it is disposition alone. Seven years would be insufficient to make some people acquainted with each other, and seven days are more than enough for others.

Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility 1811

Empathy

Patricia Piccinini places empathy at the heart of her practice. In The Long Awaited, the boy is not only comforting the creature but drawing comfort as the artist observes: ‘he’s nurturing her as much as she’s being nurtured’. The tenderness of the moment dominates. It is a work that attests to philosopher Arne Naess’ observation: ‘We cannot help but identify ourselves with all living beings, beautiful or ugly, big or small, sentient or not.’

In her video work, The Gathering, Piccinini reflects on how accustomed we are ‘to seeing everything from our perspective.’ Are the creatures threatening or curious? And why does one reveal its pouch of children? The sense of unease never dissipates emphasising our lack of understanding and the possibility that the girl is asleep in their world.

‘Goodbye,’ said the fox. ‘And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.’ ‘What is essential is invisible to the eye,’ the little prince repeated, so that he would be sure to remember.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince 1943

Transience

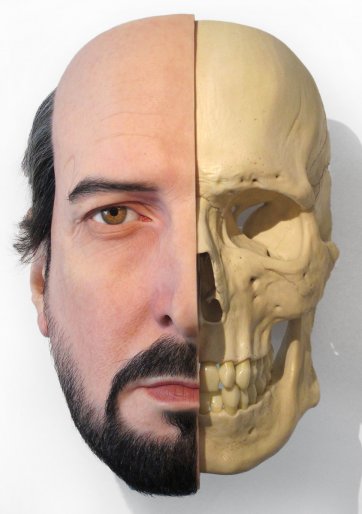

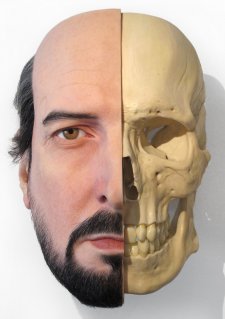

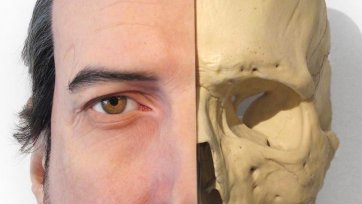

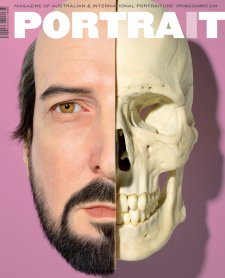

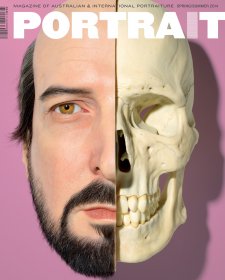

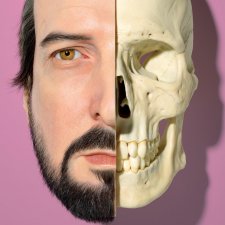

These paintings by Juan Ford and sculptures by Ron Mueck and Sam Jinks portray the awareness of non-existence that pervades human life. Art has a long tradition of reflecting the transience of human life in the memento mori. In Divide Jinks plays with his memory of owning an anatomical model as a child ‘and how those ideas of death, the fragility and robustness of the body were very abstract ones’. During his Rome Residency Juan Ford painted ancient sculpted heads to acknowledge how ‘in spite of their fractured state, like a cicada shell retaining the shape of the insect, the trace of the life force of these people was left in these faces.’ The old woman of Ron Mueck’s Untitled seems still and silent in the pause between breaths. The realism of her skin and form under the bedclothes makes the pause palpable.

In between the breaths is the space in which we live, between the before breath and the after breath is the field or realm in which time exists and then ceases to exist.

Laurence Durrell, The Avignon Quintet 1974–85

Transition

Against a synesthetic field of loud, vibrating colour, painted for this exhibition by Jan Nelson, stand the quiet, introspective, private figures of Walking in tall grass paused between childhood and adulthood. We fix adolescence as the time of inner turmoil, private worlds and secret refuges, doubt and imagination, protest and liberation. The human mind and body never really leaves this state of transition. Layered within Jan Nelson’s work is personal experience of her own formative years during the social, political and cultural tumult of 1960s. Building Walking in tall grass since 2001, Nelson’s figures are composites of individuals timelessly placed. Strange Days is from Nelson’s new series of work. It is also a composite: ‘The sculpture is part self-portrait, my memory of myself, and a girl I saw at Occupy Melbourne.’

Strange days have found us

And through their strange hours

We linger alone

Bodies confused

Memories misused

As we run from the day

To a strange night of stone

The Doors, Strange Days 1967

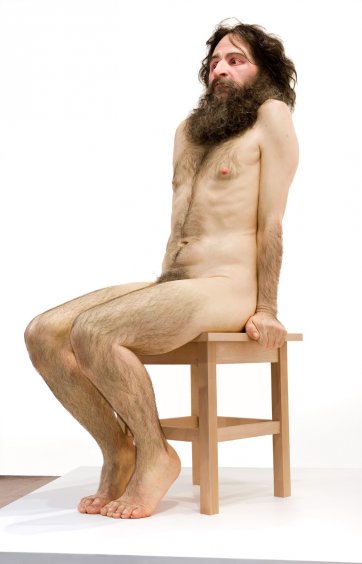

Vulnerability

The wild man and the pregnant woman are displaced archetypes of humanness: the energy and active life-giving force of the mother and the untamed man with unrepressed desires and violence who has lurked in the wilderness as an embodiment of fear from ancient times. This embodiment of man’s aggressive animal nature perches uneasy, afraid and intimidated. The pregnant woman’s pose is the opposite of the characteristic belly-held stance of pregnancy – the baby to come does not define her as she closes her eyes in her own place. Vulnerable, despite their monumental scale, our sympathy is engaged by his fear and her exhaustion, breaking their archetypal moulds. Flattened and constructed of form and colour, Petrina Hicks’ photographic series Greyscale emphasises the artificiality and fragility of the archetype.

Why, thou wert better in thy grave than to answer with thy uncovered body this extremity of the skies. Is man no more than this? Consider him well. Thou owest the worm no silk, the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume. Ha! Here’s three on’s are sophisticated. Thou art the thing itself: unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art. Off, off, you lendings!

come, unbutton here. [Tearing off his clothes.]

William Shakespeare, King Lear Act 3 Scene 4 1604

Alienation

Melbourne artist Yanni Floros and US-based Robin Eley examine the ways in which we alienate ourselves from our humanity in contemporary life. Segregated from their fellow humans in cellophane prisons, reference points are removed, so it is not certain whether these naked figures could be unwrapped, are about to be subsumed, or will forever be suspended in a plastic stasis – this is the question Eley poses of our contemporary humanness in this age of digital materialism. Yanni Floros offers even less hope. All sense of intimacy, empathy or vulnerability is denied by the complete immersion of the girls in their own world. How do you approach these humans? You are left with the texture and fall of their hair and clothes to make a connection.

Soon silence will have passed into legend. Man has turned his back on silence.

Day after day he invents machines and devices that increase noise and distract humanity from the essence of life, contemplation, meditation … Tooting, howling, screeching, booming, crashing, whistling, grinding, and trilling bolster is ego. His anxiety subsides. His inhuman void spreads monstrously like a grey vegetation.

Jean Arp, Sacred Silence in On My Way 1948

Restlessness

Most of Natasha Bieniek’s subjects are reclining, but none are resting – they have in the artist’s words a ‘melancholia, restlessness and uneasiness.’ Bieniek works in the 16th century tradition of the European miniature portrait, mirroring the size at which we again treasure, observe or share portraits – now on handheld devices. The miniature also forces an intimate encounter with the work and subject.

Simultaneously, the keyhole perspective compels a tense acknowledgement of the subject’s private human moment of emotion. This discomforting conflation of the private and public image is symptomatic of a contemporary unease. Though laboriously working up the layers on the tiny faces of herself and her friends ‘where one mistake can throw the whole’ Bieniek recognises human fragility when captured in moments of feeling.

… it is a very serious thing to have been watched. We all radiate something curiously intimate when we believe ourselves to be alone.

E.M. Forster, Where Angels Fear to Tread 1905

Reflection

A coincidence of intense self-reflection and the motif of the play-weapon occurs in the work of Melbourne artists Juan Ford and Michael Peck. These works confront the notion of the natural self. Michael Peck remembers his childhood and now observes his own children: ‘It is not my intention in these works to glorify war but to pose the question of why we are interested in it as children and raise those ideas of innocence and experience.’ Partly inspired by the makeshift guns created by a friend’s child, the figurative spectre of Ford’s intensely introspective and physical ‘challenge, negotiation or war’ to make the work stands against blue skies: ‘The body’s neural function, nervous system, everything about the physical effort, is transmuted in the medium so the soul of the thing and the thought are embodied.’ Both Peck’s and Ford’s introspection is outward-looking and contextualised by the mind’s comprehension of the relationship between the self and the world.

Any being that stands outside of nature and might be described as a human subject can be said to possess consciousness of self, the capacity for self-reflection

in which the self observes: I am myself part of nature.

Theodor W. Adorno, Problems of Moral Philosophy 2000

Mortality

In Western religious art a Pietà, also called a ‘Lamentation’, is an image of the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Christ. Jinks’ Pietà also references the Buddhist meditation practice of visualising the decay of one’s own body as a means of bringing the mind to terms with the body’s inevitable end. Jinks contemplates the limits of humanism and secularism. He reflects on Michelangelo’s Pietà at St Peter’s Basilica as a comfort to people of faith, a practical image for coping with life’s suffering: ‘How do you make an image now that gives comfort in this way? I made Pietà at the same time as my grandmother was dying. She was someone I had grown up with and was close to. People are left out on their own in the 21st century.’

Beauty and goodness, And Grief and pity, alive in the dead marble, Do not, as you do, weep so loudly, Lest before time he should awake from death, In spite of himself ...

Giovan Battista Strozzi il Vecchio’s poem on Michelangelo’s Pietà at St Peter’s Basilica quoted in Vasari’s Lives of the Artists 1550

Acceptance

Patricia Piccinini’s photographic series SO2 and The Fitzroy Series explore human acceptance of difference – applied empathy – through children’s interactions with trans-species creatures. Piccinini created the siren mole ‘SO2’ as a fictional successor to the world’s first synthetic micro-organism made from inorganic chemicals – labelled ‘SO1’. The Fitzroy Series features ‘The Bottom Feeder’ – a creature specifically designed to eat rubbish. Piccinini works where diverse, potentially irreconcilable, elements of our humanness collide: ‘The world I create exists somewhere between the one we know and one that is almost upon us … My creatures, while strange and unsettling, are not threatening. Instead, it is their vulnerability that often most comes to the fore. They plead with us to look beyond their unfamiliarity, and ask us to accept them. It is surprising how quickly we grow used to them …’

But they don’t go away. They stand, they stare … Mostly they want to look

at him because he is so unlike them.

Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake 2003