On the face of it, the decades either side of 1900 look like redefining times for Australian women. Between 1883, when Australia’s first female university graduate, Bella Lavender, completed her degree at Melbourne University, and 1921, the year that welfare worker and mother of five Edith Cowan became the first woman elected to an Australian parliament, the nation witnessed many red letter events signifying its apparent ascendancy on matters of gender equality.

Australia was, for instance, well ahead on the fundamental question of the vote, in 1902 seeing fit to pass an Act of Parliament that gave white women the right to participate in federal polls on the same terms as men. South Australia and Western Australia had accorded the same right to women at state level in the 1890s, the remaining states each following suit before 1910. Victorian suffragette Vida Goldstein became the first woman in the British Empire to stand for election to a national parliament when she contested a federal Senate seat in 1903, twentyfive years before her colleagues in the so-called mother country completed their bitter, protracted battle for the vote. Australia was equally progressive when it came to issues like divorce, maternity leave, child support and property rights, its achievements on these legal and social fronts later galvanised by the First World War and the taste it gave women of the work and wages to be had within industries that were closed to them in peacetime. Questions of equality or ‘a woman’s place’ came to occupy space within public consciousness to the degree that many felt free to experiment with methods of loosening the societal straitlacing that, up until then, had invariably pointed most women’s lives in marital, maternal and domestic directions. The average woman ‘has belonged to her parents and belonged to her husband’, suffragette and social reformer Rose Scott had declared in the 1890s, ‘and now at length she demands she should belong to herself!’ Early twentieth century Australia in consequence was a place wherein women might begin ‘taking a share in most of the professions and industries formerly considered suitable for men only’, the years between 1900 and 1910 being especially notable for the achievements realised by women with ambitions in art, writing and other creative endeavours. The century had kicked off, for example, with the publication in 1901 of Miles Franklin’s novel My Brilliant Career, whose strident teenage heroine, Sybylla Melvyn – ‘certainly utterly different to any girl I’d seen or known’ – was an aspiring writer who thought marriage ‘the most horribly tied-down and unfair-to-women existence going.’ Following its publication, Franklin honed her women’s rights credentials through association with feminists such as Scott and Goldstein before moving to Chicago where she spent nine years working for the National Women’s Trade Union League of America. Florence Taylor, the first Australian woman to qualify as an architect and later the country’s first female structural engineer and civil engineer, completed her training in architectural draughtsmanship in Sydney in 1904; and in 1906, craft worker and designer Eirene Mort opened a studio in Sydney that offered tuition in subjects such as woodworking, design, and metalwork. Mort was a prolific contributor the following year to the Australian Exhibition of Women’s Work, another substantial proof of the bold, optimistic mood permeating the decade.

A celebration of women’s achievements in such pursuits as painting, photography, horticulture, woodwork, teaching, nursing and furniture design along with the more traditional cookery and needlework, the Exhibition occupied the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne for almost six weeks during October and November 1907 and was conceived as an opportunity for women ‘to determine for themselves the occupations for which they think they are best qualified, and by the pursuit of which they may reasonably hope to secure an adequate position of independence’. In painting’s case, the pre-Great War years were those wherein Thea Proctor, Margaret Preston and others of their remarkably accomplished vintage first embarked on periods of study and travel abroad – both of these being pursuits which fell safely within the definition of what was ‘appropriate’ for genteel, respectable girls with artistic inclinations. Twisting this definition to their advantage, Proctor, Preston and their contemporaries became leading players in the modern art scene on returning to Australia, their lives and their work combining to exemplify progression and change.

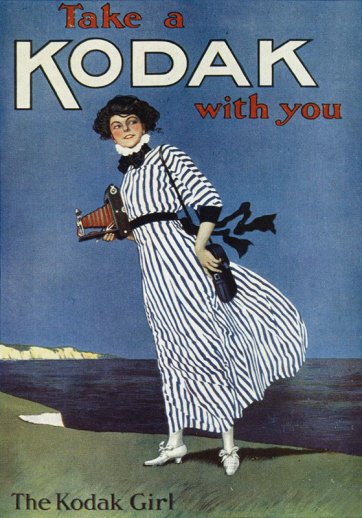

Though less documented than those of painters, the careers of women photographers are possibly more instructive in demonstrating the impact of the melding of recently-won rights with shifting ideas about duty and femininity. The early part of the twentieth century is just as notable for the number of professional female photographers it produced, the modernity and mobility embodied by photography aligning easily with developing professional prospects for women. As historians Barbara Hall and Jenny Mather have explained: ‘Traditionally, painting and sculpture belonged to the world of the establishment, the world of men, institutionalised and exclusive on the professional level.’ Photography, in contrast, as a more democratic medium, is argued to have been free of the fine art world’s old-school-tie traditions, lending itself more readily to the admittance of female practitioners and allowing them to participate unquestioned. The medium was more accessible to women also by virtue of technology, the late nineteenth century being the age of celluloid negatives as well as the Kodak camera and other lighter, user-friendly and domesticscaled models which enabled women to become accomplished amateurs, if not professionals. Photographic companies deliberately pitched their wares at leisured women, promoting their specialities in ‘hand cameras for ladies’ and, in Kodak’s case, manufacturing the image of the ‘Kodak Girl’: a perky, camera-wielding exemplar of new, socially mobile and independent womanhood. Admittedly, photography’s accessibility led to it being dismissed by detractors as a hobby rather than a ‘serious’ art form: ‘You press the button, we do the rest’, as Kodak’s advertisements claimed. Women, by implication, were reasoned to be ‘naturally’ more suited to such a simple, inferior sort of thing – a perception that, as Helen Ennis has explained, was among those that ’tended stereotypically to justify women’s use of the camera while placing them in suitably subordinate roles within the art world’. In photography’s case, this often meant women were consigned to repetitive junior roles in studios, responsible for hand-colouring and retouching and other tasks necessitating a ‘delicate’ touch. Yet photography, like the fine arts and other ‘harmless’ feminine pursuits, remained something that women were better enabled to pursue professionally. The New Zealand-born photographer May Moore (1881–1931), who established her own studio in Sydney in 1910, was one of many women who proved photography’s worth as a means of achieving economic independence and critical success.

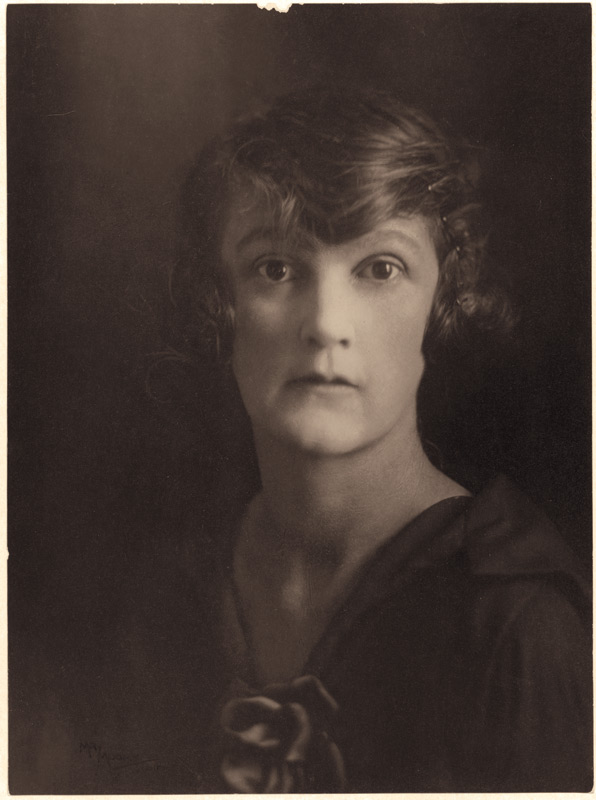

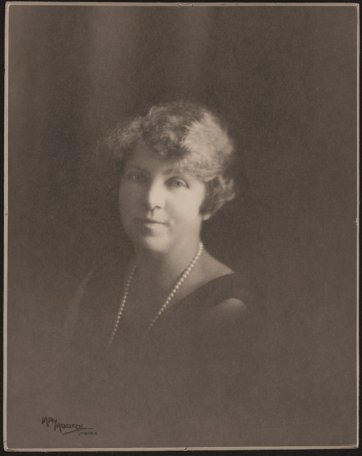

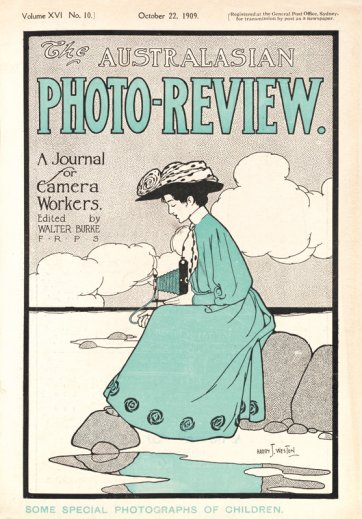

Born near Auckland in January 1881, May Moore was ‘of an artistic family’, according to a profile of her published in the Lone Hand in 1917, and ‘at an early age showed signs of unusual ability, both as a portrait painter in oils and also as a miniature painter.’ Moore studied at Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts around 1900 and by 1908 was in Wellington, working as a painter from a studio on Willis Street which she shared with a portrait photographer and where she thus picked up her first taste of the trade. Moore’s experimentation with photography, initially an ‘amusement’, gradually became her focus, her sitters for photographic portraits becoming ‘so numerous that she found herself devoting more time to photography’ than to painting. Moore then purchased the studio for herself and with her younger sister, Mina (1882–1957), soon became known for a shadowy style of photographic portraiture which, in the words of curator Gael Newton, employed a lighting technique that ‘left much of the picture in rich, dark brown tones and picked out the main profile or features with a pencil of light from one side’. Examples of May’s work first appeared in the Australasian Photo Review, in an issue featuring ‘some special photographs of children’, in October 1909 and year later, another photographic journal was announcing its pleasure at the arrival in Sydney of ‘Miss May Moore, the well-known portrait photographer of Wellington, New Zealand’. Offered the use of a studio in the Bulletin building, Moore was introduced to an artsy, somewhat Bohemian set, some of her first Sydney subjects being men like the cartoonists David Low and Livingston Hopkins. Her portraits, in the opinion of one 1910 reviewer, were ‘simply exquisite’: ‘there is a subtle distinction about her studies which places them in the first rank of this class of work, and as totally removed from the accepted portrait, which is hard and shiny, and more often than not quite unlike the sitter’. By early 1911, as her ads in the Sydney Morning Herald demonstrate, May had found her own premises and was enjoying enough success to justify Mina’s relocation to Sydney to assist in the business. In 1913, they opened a studio at the ‘Paris end’ of Melbourne’s Collins Street, which was managed by Mina and which became the portrait studio of choice for numerous visiting performers by virtue of the sisters’ interest in and associations with theatrical types, and the studio’s location in a building owned by the prominent theatre entrepreneurs, J & N Tait. Although not unique to them, May and Mina Moore perfected the dramatic and moody Rembrandt lighting style, applying it to great effect with sitters who ‘figured in the realms of art, music and literature’ and in their many portraits of recentlyenlisted World War One servicemen.

Though motherhood led to Mina’s retirement from the business and the sale of the Melbourne studio in 1918, May continued to practice following her 1915 marriage to a Sydney dentist named Harry Wilkes, eventually developing what an obituary of her described as ‘a business and a reputation that were the envy of many competing concerns’. Admittedly, she was advantaged in being married to the type of husband, rare at the time, who was content for her to be a breadwinning wife and who managed her studio for a period when her health deteriorated in the late 1920s. Yet by her own example, Moore continually disproved the stereotype – that emerged as women claimed greater stakes in creative fields – of the ditsy dilettante indulging in photography as a socially sanctioned or agreeable diversion, instead adding substantially and consistently to support for her professed belief that ‘photography is decidedly a calling well-suited to a woman, especially if she has imagination, and plenty of perseverance’. Interestingly, though quoted as being one conforming to the opinion that women were better suited to certain ‘delicate’ aspects of photographic work, Moore seems to have made a point of seeking only ‘smart young GIRLS’ as employees and as apprentices for behind-thecamera roles. The ideological reasons underpinning women’s altered social status are also strongly alluded to in her output which, in addition to likenesses of ‘practically every artist, musician, critic, journalist, story-writer and poet of local celebrity’, included those of women, like herself, whose careers, lives and works offered explorations of the new roles and ideas in play for Australian women at the turn of the century. Among May’s hundreds of subjects were feminists and social reformers like Rose Scott, a pioneer of the women’s rights movement in New South Wales; and Mary Gilmore, the first female member of the Australian Worker’s Union and editor of its newspaper’s women’s pages between 1908 and 1931. Writers and poets including Ethel Turner, Amy Mack, Katharine Susannah Prichard, Dorothea Mackellar, Mary Grant Bruce and Dulcie Deamer (Sydney’s self-styled ‘Queen of Bohemia’) were some of the other sitters Moore depicted, as were the artists and illustrators Hera Roberts and Thea Proctor, both of whom are remembered for having authored potent, assertive images of modern womanhood.

Just as Proctor’s iconic cover designs for The Home magazine were dismissed by some for being decorative – ‘flat, primitive coloured things’ in the words of Norman Lindsay – Moore’s work was occasionally commented on in terms which emphasised its quaintness or curiosity as that of a career-minded ‘lady’. Some considered her an anomaly in being a woman in whom ‘an unusual degree of artistic ability and business aptitude’ were combined, while others were inclined to underline the acceptably and unthreateningly feminine aspects of her practice. ‘May Moore has always been particularly happy in her results when photographing children’ opined one male writer in the Australian Woman’s Mirror in 1925, before going on to list her skills at needlework, jam-making and other marks of ‘delightful’ domesticity. But rather than diminishing her strength as a case study in women’s moves towards equality, such comments merely reaffirm the way that Moore and her cohorts might renegotiate existing circumstances to achieve creative, independent ends. By way of her life and her portraits, May Moore created ample evidence of the way in which women could be emboldened by the social and political changes of her times.