In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Polonius advises his son Laertes to spend all he can afford to attire himself well ‘for the apparel oft proclaims the man’. The complex iconography at work in the history of dress in painting is a study in and of itself. When it comes to painted portraits, suffice it to say that clothes very often make the man, but in the case of women subjects, especially by male artists, clothing is often employed to disguise the sitter in order to satisfy artistic intent.

The female subject as blank canvas is a well-known artistic conceit. The artist divests the sitter of personal qualities in order to create a persona. This is achieved by investing a body with attributes such as clothing, pose and setting. Clothing has particular significance in this regard, as it is usually the first thing we, as viewers, assess, after locking eyes on the figure. Sometimes this practice is evident in commissioned portraits of identifiable sitters, and occurred at their request (or their husband’s), but more commonly it stems from artistic will.

The motif of clothing as disguise is found throughout literature, and is broadly used in language, in particular through idiomatic expression, such as ‘a wolf in sheep’s clothing’. In art, the effects of clothing on characterisations are more subtle. The female figure in art has always been subject to attributions of character created entirely by the appetites and imaginations of their male viewers/critics. The 17th-century poet Robert Herrick, of ‘gather ye rosebuds’ fame, recorded that ‘sweet disorder’ in a dress was suggestive of wantonness. In her acclaimed study of the history of dress, Seeing Through Clothes (1978), art historian Anne Hollander points out that ‘sartorial dishevelment for women’ was commonplace in 18th century French portraiture, where its sexual charge related to perceived submission. In Feeding the Eye (1999) Hollander proffers that images of white feminine dress are highly sexually charged, precisely because they are commonly perceived to portray virtue or innocence. Depictions of feminine radiance encourage licentious musings and invite ‘the stain from life’s dome of many-coloured glass’, such as the ‘readiness of a milky skin to blush’. Amongst the many portraits of women sold at auction in Australia, unidentified portraits titled with reference to a female sitter’s dress alone are fairly common, and feature in many top ten results for the respective artists. Tom Roberts’ 1893 portrait of Mrs Dodds in a white dress sold for $84,000 in 2008 under the title The White Dress. In 1995, an unidentified portrait by Roberts titled The Blue Dress made $109,000 against an expectation of $25,000.

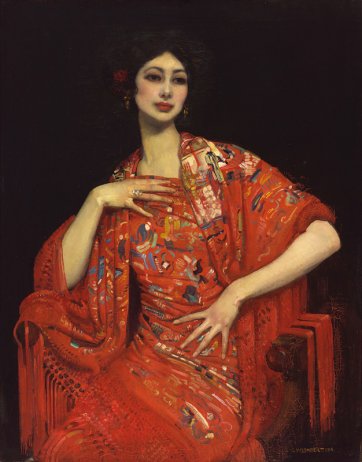

In 2005, George Lambert’s 1905 portrait of Sybil Waller in a work titled Red and Gold Dress sold at auction for $120,000. If white and blue promises feminine virtue (and thus the potential taking thereof ), portraits of women in red enable a much richer flight of fancy, especially when clothed in exotic costume. Waller is depicted seated in a medieval chair wearing a bejewelled 15th-century Italian dress. The catalogue entry for this work in the National Gallery of Australia’s 2007 Lambert retrospective notes that the artist infuses the painting with highly charged sensual overtones through the addition of two figures in the imaginary landscape: a naked ploughman with two white horses on one side and a nude woman resting under trees on the other. From the same exhibition, The Red Shawl 1913, is a sumptuous work by Lambert from the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The sitter, Olave Cunninghame Graham, was the niece of one of Lambert’s friends. The catalogue entry for this work describes how she wrote to the artist shortly before her marriage, expressing her want ‘to see my portrait hanging in our dining room instead of stored away in your studio’, which never eventuated.

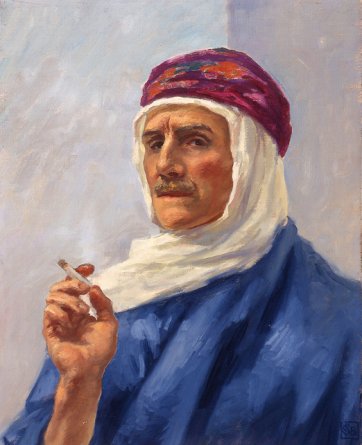

The appeal of exotic opulence in portraiture was spurred by Rembrandt and his circle in the 17th century, and the occurrence of portraits in oriental costume continued throughout the 18th century with commissions from the elite. One such person was Edward Wortley Montagu, a linguist specialising in Arabic and Mediterranean languages, his 1775 portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, London depicts him in full Turkish costume. This fascination peaked in the 18th century, but was brought to life again with the advent of photography and the archaeological discoveries of the 19th century. Dressing a la Turque became a popular subject for romantic pictorialists, such as Frederick H Evans, whose 1901 portrait of F Holland Day as a Moor epitomises the trend. This appetite continued throughout the 1920s, where generic opulent Arab costume was sometimes worn by elite society women as fancy dress. A catalyst for this appeal was the enormous popularity of Valentino’s Arab portrayals in the The Sheik (1921) and its sequel, and the romance and mystique surrounding Lawrence of Arabia. British war hero, Colonial TE Lawrence, was instrumental in the Arabs’ campaign against the Ottoman Empire. He became famous as Lawrence of Arabia after American journalist Lowell Thomas released film footage of his exploits in 1919. The portrait by Augustus John from the Tate Gallery, London, was painted in Paris in 1919, where Lawrence, who routinely wore Arab dress, was championing the cause of King Feisal and the Arabs during the Peace Conference.

Australian painter Rupert Bunny lived in Paris at the time, and would likely have known about the portrait through his circle of friends. His Self Portrait in Arab Dress, circa 1920, is clearly influenced by the persona of Lawrence, if not John’s portrait. Bunny characteristically depicts himself with a cigarette, which, apart from contextualising the portrait as 20th century, works as a stand-in device for the self portrait painter’s brush. In a 2009 review of the Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition, Rupert Bunny: Artist in Paris, art historian John McDonald referred to Bunny’s secretive personality and his homosexual relationship with a British art student in the early years of his Paris domicile, long before he married French model and artist Jeanne Morel in 1938, who became his muse and regular model. Lawrence, too, was known for his secretive personal life, and questions surrounding his sexuality are commonly noted by historians.

Rupert Bunny painted many portraits of his wife, Jeanne, often anonymously or in character. Three such works dominate the artist’s records at auction, and all are interesting examples of portraits in disguise. Portrait of the Artist’s Wife Jeanne as Saint Cecile (Cecilia) has appeared twice, selling in 2003 for $129,500, and originally in 1989, under the title Saint Cecilia (Cecile) for $143,000, when it was acquired by the noted Bunny fan and art patron, John Schaeffer. Bunny composed music after 1933, and St Cecilia is the Catholic patron saint of music. This beautiful image, alas in a private collection and unavailable for reproduction, depicts the saint in classicising draped clothing, bathed in a golden light, looking heaven wards, her hair adorned with the roses given unto her by angels. Cecile apparently informed her Roman husband after marriage of her chastity vow to God. This inspired his conversion, which provoked his murder and her subsequent martyrdom. Depicting women as saints is nothing new. The 17th-century portrait of Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland as St. Catherine of Alexandria is one of countless examples of aristocracy buying virtue by virtue of the brush.

Schaeffer sold a number of works by Bunny in his single collection sale of 2003. The Fan (The Artist’s Wife on the Balcony) realised $118,000, while Femme Au Miroir; Woman Before a Mirror made $240,000. The latter fits perfectly with Hollander’s take on the Impressionists’ use of mirrors to diffuse light and act as a vehicle for colour. Here, her so-called ‘dispassionate mirror’ device also serves to create a rear view ‘fashion plate’.

Hollander also comments on the artistic tradition of depicting the clothed body ‘as an example of ideal dressed perfection … appropriate to a different group – or a different time, or a certain role’. In The Fan, Bunny is channelling the Aesthetic Movement’s Cult of Japan, also at work in the oeuvres of the Impressionists. Both James McNeill Whistler and Claude Monet painted models (mistress and wife respectively) in highly decorative kimono, holding fans and surrounded by Japanese accoutrement. The most famous example of this practice is the portrait in Whistler’s Peacock Room, Rose and Silver: The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, 1864, which is a portrayal of Christine Spartali, daughter of the Greek consul.

Whistler’s portraits are, in effect, a synthesis of his interests in music and painting. This is reflected in titles such as Caprice in Purple and Gold, No.2: The Golden Screen, 1864, and the Symphony in Flesh colour and pink: Mrs Leyland, 1871–74, who was the wife of the magnate for whom the Peacock room was designed. This particular pattern of disguising portraits is exemplified by another of his most famous works, Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother 1871.

Disguising sitters by depicting them in clothing of other personae generally attracts a premium on the market. Titular reattribution is also a significant factor in value fluctuations at auction. When offered at auction in 1998 under the title The Blue Dress, Hilda Rix Nicholas’ portrait of a young woman in a slumped pose made $23,000. Eight years later, and with a new title of Picardy Girl, the work soared to $96,000. A new title, reflecting research, offered a reason for the girl’s demeanour, and significantly altered the work’s desirability.

And, as it turns out, the apparel doesn’t always proclaim the man. Thomas Stewarts’ portrait of Chevalier d’Eon, soldier, diplomat/spy and transvestite who lived in London from 1762– 1777 as a man, and from 1786– 1810 as a woman, was catalogued as Woman in a Feathered Hat by Gilbert Stewart in a provincial New York sale in 2011, where it fetched us$10,000. The sleuthing dealer who acquired the work had figured stubble was a sure sign of a deeper mystery and, less than a year later, sold the re-attributed work to the National Portrait Gallery, London for £45,600.