Pop Art Portraits is the first exhibition to examine the role and significance of portraiture within Pop Art. As such, it addresses one of the major art movements of the late twentieth century, whose subject matter, imagery, themes and principal protagonists have all become instantly familiar through numerous exhibitions, catalogues, books and articles.

This familiarity has resulted in the widespread assumption that the essence of Pop Art is known, the historical perspective formed and ‘set’. Viewed in the context of the consumer society from which Pop Art emerged, the received wisdom is that Pop is an art about objects. Pop Art Portraits contests that view, proposing nothing less than a fundamental reassessment.

In the last forty-five years, the dominant tendency has been to see Pop Art as a visual response to a materialist culture that reached new heights in the 1960s, its imagery taken from the mass-media world of advertising, magazines, television and film. With the advent of exciting technological and cultural innovations, expressed through fashion, food, design, pop music, cars and space travel, the 1960s promised a progressive vision for the future rooted in consumer values. Pop Art, it is said, became synonymous with the fabric of this new society, a world dominated by standardisation, repetition and predictability.

These ideas certainly played an essential part in the way Pop developed growing affluence in Britain and America in the 1950s and 1960s went hand-in-hand with mass production and mass consumption. Pop Art is inextricably linked with such phenomena and it is telling that the epitome of Pop, Andy Warhol, has become identified in the public mind with images of Campbell’s soup cans. But the real significance of Pop Art is more complex than this identification with objects would imply. Seeing Pop solely in terms of the material fabric of the society that nurtured it places an undue emphasis on things rather than people. Critics such as David Sylvester, who have argued that Pop was ‘more often a form of still-life painting than of figurative painting’, have powerfully influenced the way Pop has come to be viewed.

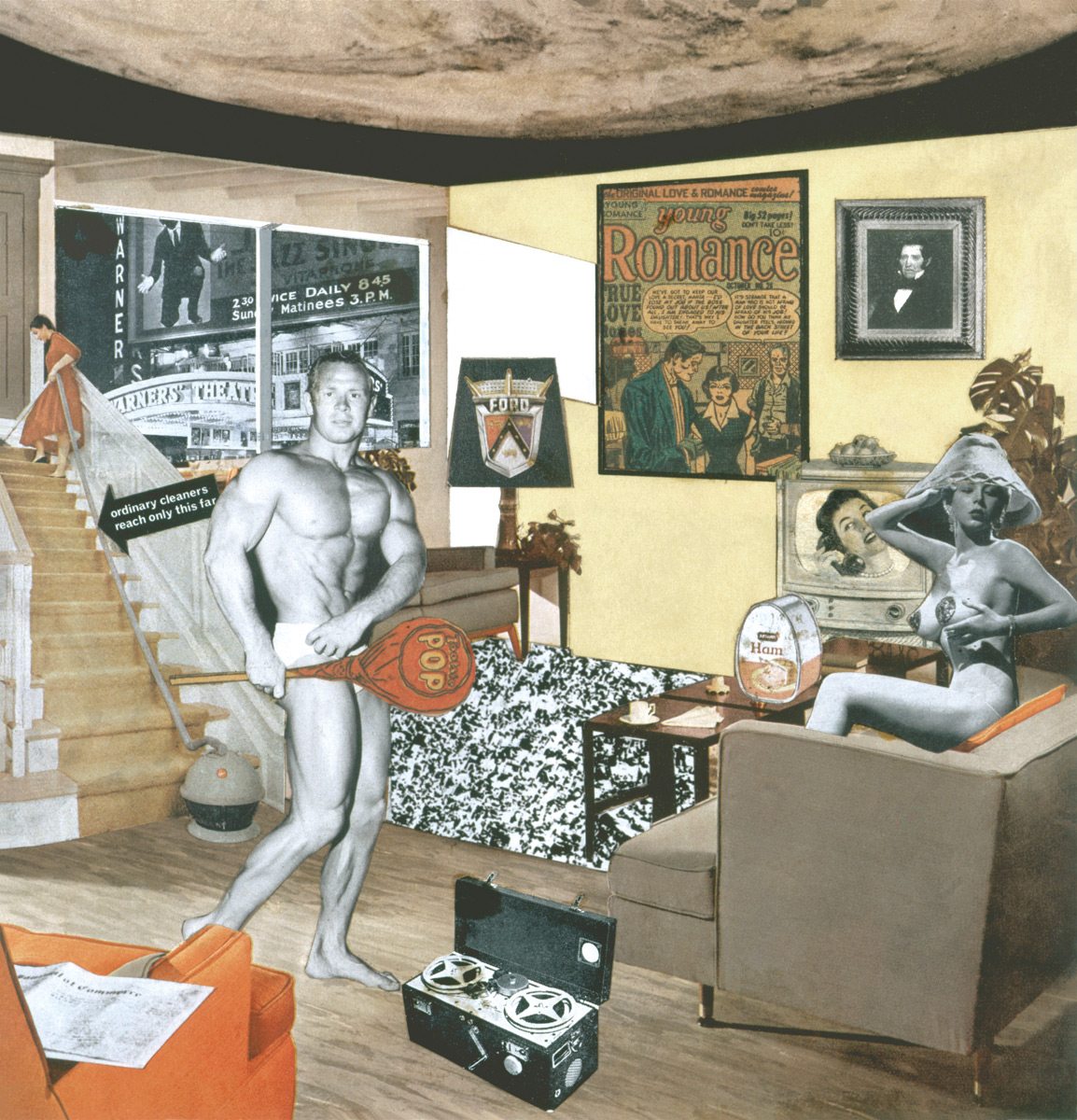

I have long felt that this perception of Pop Art is accurate but unbalanced and so, when I joined the National Portrait Gallery in 2005, I set out to take a fresh look at Pop, in terms of portraiture. Pop, it seemed to me, while closely linked with the depiction of things, was pre-eminently a figure-based art. Wherever one looks, the iconography of Pop is replete with portraits of many different kinds, with figures shown either as consumers interacting with their enhanced world of objects, or seen in isolation so that people become the main focus of attention. This is true of Pop’s earliest manifestations from the 1950s: Eduardo Paolozzi’s seminal BUNK! collage depicting the strongman, Charles Atlas; Richard Hamilton’s iconic Pop image Just what is it that makes today’s homes so interesting, so appealing, which teems with portraits; and Jasper Johns’s plaster assemblages containing casts from life. The subsequent development of Pop Art reveals an obvious, growing fascination with portraits, from those of media celebrities such as film stars, pop musicians, entertainers, models, politicians, astronauts and comic-strip characters, to images of anonymous people, all taken from mass-media sources. By the 1960s, in the classic Pop Art images of leading figures such as Hamilton and Warhol, portraits have attained an iconic presence. My central argument is that people and objects are the two inseparable halves of the brave new world addressed by Pop Art. If Pop can be said to have a subject, then it is mankind’s changing condition in a consumer society. But it is only by acknowledging the presence of portraits in the iconography of Pop that this subject makes any sense.

The aim of Pop Art Portraits is therefore to redress this imbalance by examining in detail the complex and subtle relationship between portraiture and Pop Art. In both America and Britain, Pop Art evinced a fascination with images of famous people. For that reason, portraits of the famous are in evidence throughout the exhibition. But it would be overly simplistic to claim that Pop’s engagement with portraiture was simply a matter of appropriating images of famous individuals and then infiltrating them into a context inspired by the mass media. For example, in America the progressive infiltration of portraiture had a singular importance in challenging the dominant legacy of Abstract Expressionism.

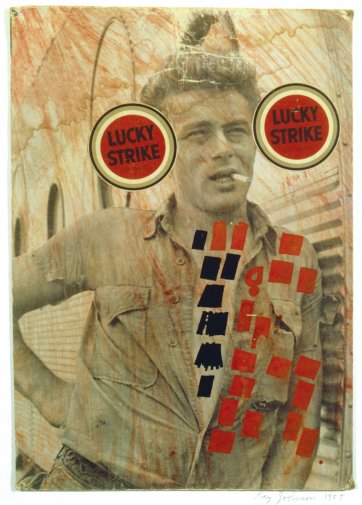

Rather, the subject goes way beyond the straightforward depiction of recognisable people in a modern setting, and Pop Art portraits are rarely simply a matter of hero worship or of direct quotation. In the hands of such artists as Warhol, James Rosenquist, Hamilton and Robert Indiana, portraiture reflects an interaction with the visual language of their mass-media sources. Several of these artists’ responses also reveal an intense interest in the mechanisms of fame, the processes that transform an unknown person into a celebrity, and the consequences of that transformation.

The story is made still more complex by the way in which, alongside overt representations of familiar figures, portraits of a quite different kind can also be found. The figures depicted by Mel Ramos and Tom Wesselmann have, in the past, been taken to be mere ‘types’, not recognisable as portraits in the conventional sense at all. Such images exemplify another theme of Pop Art portraiture – that of the covert or hidden portrait, in which the identity of the sitter is concealed or not made obvious, even though such images are derived from real people. In some instances, for example, early works by Jim Dine, David Hockney and Allen Jones, the images appear anonymous but actually depict the artists themselves.

Alternatively, artists such as Paolozzi, Robert Rauschenberg and Hamilton appropriated images of anonymous figures from mass-media sources, taking whatever seemed to them to have a stimulating vitality, interest or relevance to their needs. Although unidentified, such figures are real people whose identities have been obscured by the process of recontextualisation. These threads, too, run through this selection of works, manifesting an interest in the way in which commercial advertising, and also the creation of portraits in a fine-art context, can mask and even obliterate an individual’s personal identity.

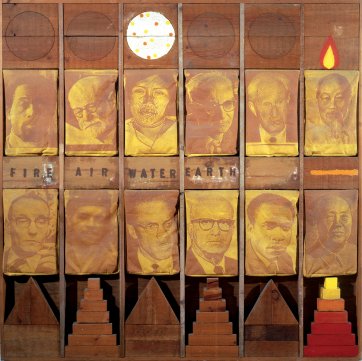

A further, fascinating aspect of Pop’s engagement with portraiture was the singular way in which it extended the genre through the creation of fantasy or imaginary subjects. In this respect, Paolozzi’s early collages based on Time magazine covers, made in the early 1950s, are of seminal importance. By dismembering recognisable portraits and then reassembling the fragments in new combinations, Paolozzi shattered the boundaries of portraiture. The image of an actual individual is replaced with one that reads as a newly fabricated, invented, portrait. Other artists such as Nigel Henderson, Derek Boshier and Colin Self developed the process further, creating compelling, highly particular portraits of imaginary sitters. Rauschenberg, Richard Smith, Jones, Hamilton, Claes Oldenburg and Allan D’Arcangelo took a related but different direction, creating portraits of identifiable sitters in which the means of representation is non-literal or the appearance of the sitter has been modified radically. In some instances, notably Rauschenberg’s Trophy V and Smith’s MM, such works initially appear completely abstract, not reading as portraits at all in any usual sense.

In shifting the focus from objects to people, Pop Art Portraits aims to give a truer assessment of the full significance of this influential art movement. Its contention is that through portraiture Pop Art addressed the changing status of the individual in a consumer-driven, celebrity-obsessed society in which human values were being rewritten.

It reflected the way in which the mass media could transform an individual by conferring instant fame but how, in the process, personal identity could be lost. This was a world in which replication was valued above uniqueness, objects were accorded a growing importance, and the individuality of the person was qualified. In a sense, objects were charged with the significance of people, and people became more like things. The exhibition traces the way in which Pop Art embraced and transformed the portrait, supplanting the religious icons of the past and creating new gods – part real and part fantasy – as secular idols for a material world.