With the expansion of artistic media, portraiture at the beginning of the twenty-first century continues to grow in variety and versatility. Catching a Likeness: Portraits on Paper reveals great diversity of style and form, and displays how portraiture has adapted and changed through the centuries.

It shows how portraits have varied depending on prevailing artistic fashions, favoured styles, techniques and media. Idealised heads feature alongside truthful self portraits, literary likenesses and caricatures, while modern portraits display more experimental approaches.

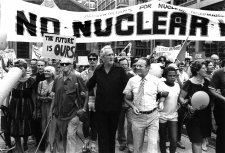

The all-pervasiveness of portraiture makes it one of the most familiar and popular of art forms. Individuals or groups are shown either full-length in well-defined settings or partially as busts or silhouettes. Portraits are found in a variety of contexts and locations: appearing in museums, private homes, public parks and on thoroughfares. Throughout history portraits have been used for a range of commemorative, dynastic, personal and propagandist purposes. Portraits provide a form of authentication of a person’s appearance, age and status, so can act as a substitute for the individual they represent.

Portraits have the dual purpose of recording specific events, such as marriages or diplomatic visits, while evoking something more enduring or permanent. A portrait also serves to magically arrest time and to extend artificially the life of the person represented, offering sitters a sort of immortality. In her book on portraiture, Shearer West writes: ‘An observation of any two portraits of the same individual by different artists reveals just how unstable ideas of likeness can be’. As portraiture represents specific people, it has tended to thrive in cultures that privilege the individual over the collective. The Renaissance in Western Europe was a time of increased self-consciousness, in which concepts of unique individual identity began to be verbalised.

From the sixteenth century the idea of private engagement with the sitter’s visage became important. This led to the rise in popularity of pastel portraits and miniatures, worn as lockets or designed to be held in the hand. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists and sitters alike recognised the publicity value of exhibiting stylistically daring portraits at public exhibitions.

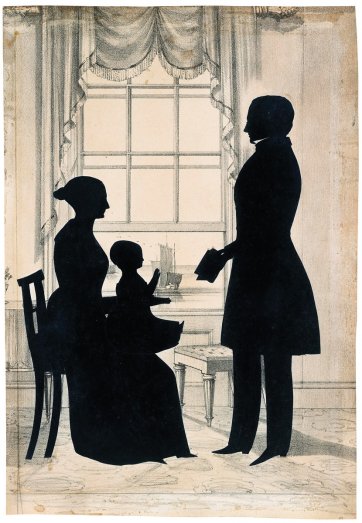

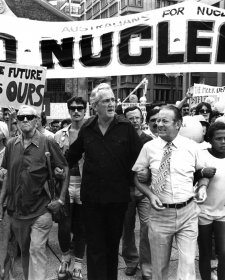

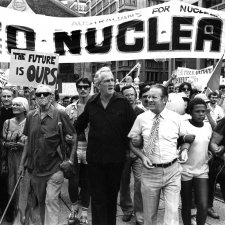

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries silhouettes, simple portraits cut out of black card, such as Augustin Edouart’s Profile of a family looking out to sea, were popular as a cheaper alternative to portraiture miniatures, and were certainly more affordable than grandiose oil paintings. Edouart introduced the term ‘silhouette’ into England, and traveled extensively through Ireland and England cutting tens of thousands of these delicate likenesses, immortalising hordes of middle-class families. Portraits of individuals usually project an idea of identity based solely on likeness, personality or social status. However, group portraits include the additional requirement of human interaction, and therefore require greater experimentation with composition, as evident in Adam Buck’s Portrait of the Edgeworth Family.

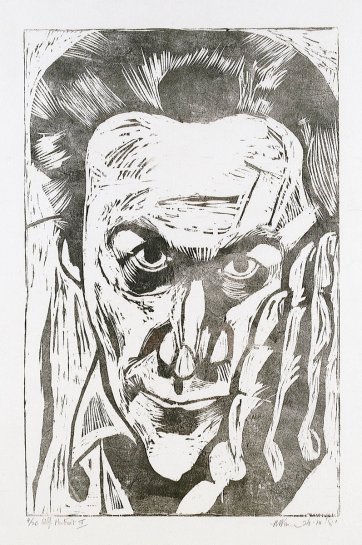

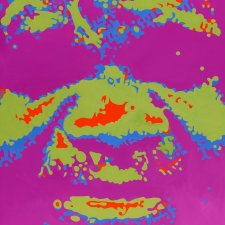

Self portraiture, where the observer becomes the observed, offers an insight into the artist’s personality, which makes it both compelling and elusive. The German Expressionists exploited the power of facial expression to convey the inner life of sitters and depicted a wide range of human emotions that signaled the psychology, spirit or soul of their subjects. The contemporary Irish artist Michael Kane, in his larger-than-life Self portrait IV, casts himself as a thinker, and confronts the viewer with a penetrating gaze.

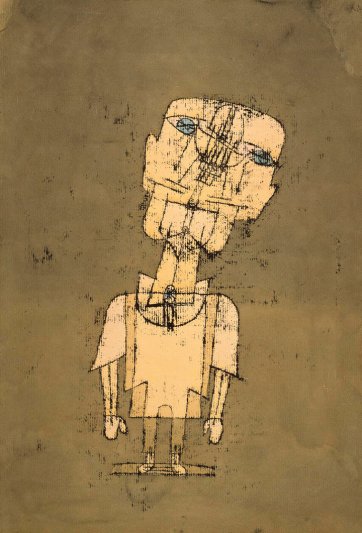

The invention of photography offered both a challenge and an opportunity for portraitists, ultimately leading to the demise of the portrait miniature. More and more artists began to make portraits that were highly experimental and dynamic. Modernist portraiture sought to draw from tradition but also to contest it. Paul Klee’s semi-abstract compositions evoking poetic colour harmonies through effects resembling mosaic, often alluded to fantasy or dream imagery. In his Ghost of a genius, the puppetlike figure, created through a process of oil transfer, may be a self portrait, as Klee had very large eyes and a domed head.