During the former Prime Minister and Mrs Howard's visit to Washington DC Mrs Howard toured the construction site of the National Portrait Gallery with Marc Pachter, Director of the National Portrait Gallery. As patron of the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, Mrs Howard and Marc Pachter were engaged in lively discussion for over an hour despite hot and humid conditions as well as the dust and dirt of an active construction site.

Following Mrs Howard's visit and in light of the exciting building project for Canberra, Ron Ramsey, Director of Cultural Relations at the Embassy of Australia interviewed Marc about the Washington DC renovation.

Mrs Howard's recent visit to the National Portrait Gallery building site obviously informed her of the complexities of such a project. How did the Washington project come about - was it driven by the Board, the Director or government? How long has the building renovation been in progress and what is the budget?

We started with practical concerns. While there had always been a broad notion that an 'ancient' (for Washington) building would need some reviving, there was no particular notion of when that would be. Then things became alarming in the state of the building in the 90's ... mind you, this is a building that is the third oldest in Washington after the Capitol and the White House - one of the grand federal buildings.

We began with a 5 million dollar project just to get the skylights and the roof back in shape. That was a daunting expense even for this relatively rich country. Then came the contemplation of the larger purpose of the restoration. This is entirely a federal building -always has been. And so there was a general, not disputed notion of federal responsibility for it. Initially we were rather modest in our requests. For a building like this bringing it back to acceptable functioning status is still something like a 64 million dollar project, which is what we asked Congress for. It seems like an extraordinary amount of money but soon we realized that we had sold short the national purpose of the building by thinking in so limited a way. Much might be done to enhance it rather than simply to preserve it.

With the arrival of the new Secretary of the Smithsonian in 2000 there was a new opportunity to think about grandeur - not only maintenance. And he really saw the possibilities. The Secretary of the Smithsonian presides over something like 18 museums and many research institutes. Congress was persuaded to devote 166 million dollars to achieve both the grander purposes of restoration and the goal of making this a modern 21st century building as well.

Aspiring to be both modern and traditional is very expensive. 166 million was committed over a period of years. We all thought that this would be a 3-4 year project. It has actually become a 6 year project (and that doesn't even include the 5 million initial restoration of the roofing and the skylights). Congress has been steadfast in all but one occasion when it looked like they were going to delay a year's funding. After public discussion Congress was moved to restore the funds. There were further needs which we proposed to meet by private fundraising. America is committed to public/private partnerships. We added a canopy to the courtyard in the spirit of the British Museum's Great Court. Congress had to validate the goal but was not expected to provide the money. We had to find that. We have pretty much found most of the required additional money ... between S50 and S60 million. We will open (without the courtyard -that will take another year and a half) in this glorious space on July 4th 2006. which happens to be the 170th anniversary of the laying of the building's cornerstone by President Andrew Jackson in 1836.

What will the remodelled building offer that the previous National Portrait Gallery did not?

Well, we will have subtle but extraordinary technological capabilities, for one. We will not have to use those hulking video machines and interactive devices. While wonderful in their day they still distracted the visitor from the art and everything else they were meant to contemplate. So we are creating a rather sophisticated wireless system which will allow the visitor to wander through with a hand held device with many levels of possibilities. For example: a national portrait gallery is interested in conveying very much the spirit and aspect of the personality as well as the face and manner caught by the artist. When, for example, the visitor encounters Martha Graham, one of our great modernist choreographers and notices her rather odd, stiff stance as captured by the artist in the 30s, they will then be able to turn to their hand held device and see her dance, see exactly the motions that inspired this perspective. Another possibility is to allow curators to indulge a whole series of educational fancies which are not really doable in other ways.

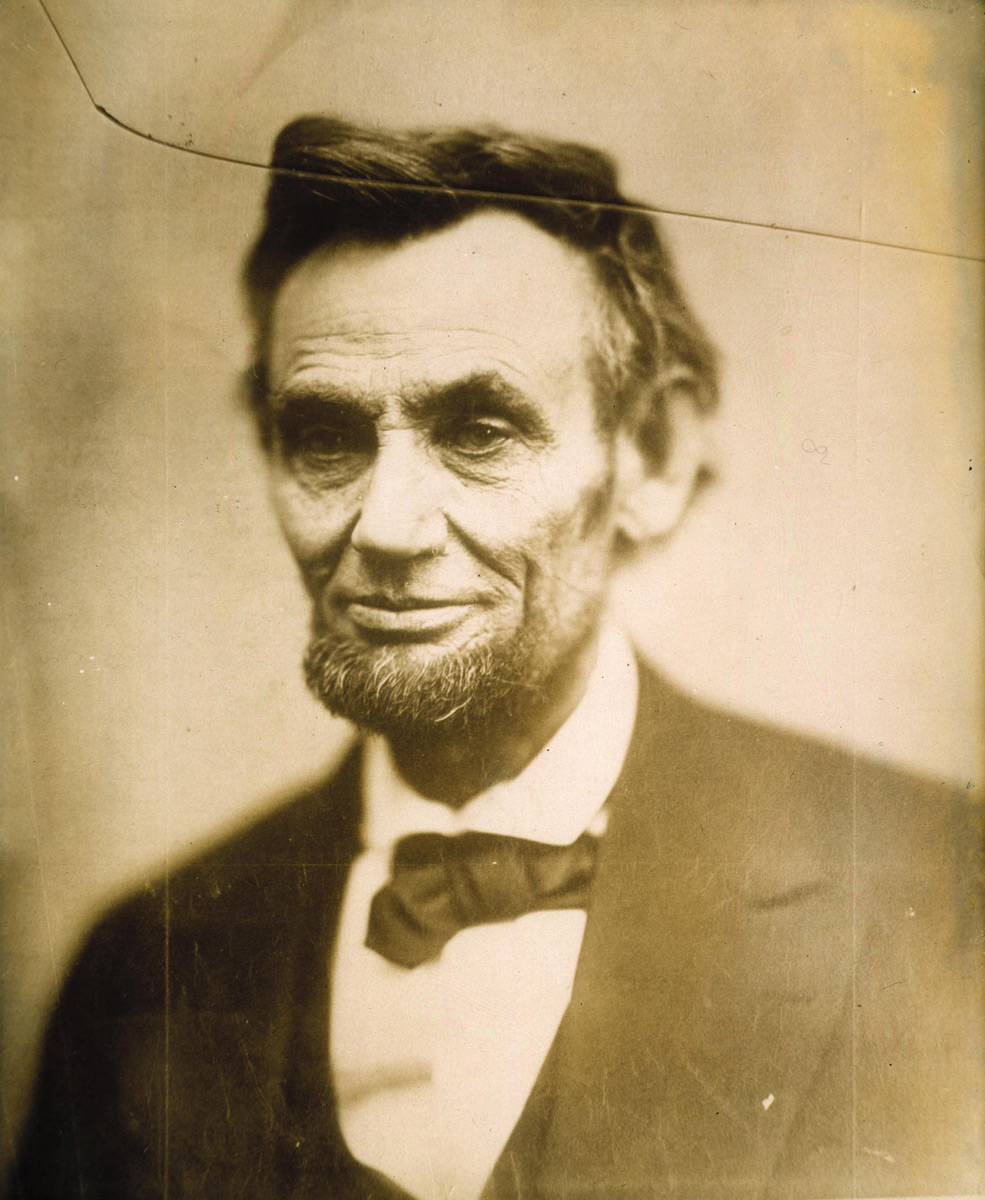

For example, I've always wanted the visitor to actually focus on the ugliness of Abraham Lincoln. It was a fundamental fact of his political career, often remarked about by him and others. Ugliness is one of those phrases never uttered in a portrait gallery certainly not in the limited space of a wall label. Now we can really allow the visitor that insight if they choose to follow this aspect of his career.

Another question we can explore with the hand held is the one of 'likeness'. We can now actually take as an example an image of any sort really, but let's take the line drawing of character in caricature and allow the visitor to remove elements of it to the point where they believe this individual is not recognisable.

We also will have an auditorium that allows us to frame another purpose. I have always felt passionately that a portrait gallery is a place of portrayal, not only of portraits in the classic sense. We've already diversified the range of people we present and diversified the range of visual media we present as well. But l don't think we have given proper credit to other modes of portraiture, for example, performance. When we ask a great actor to portray, for example, Emily Dickinson, one of our greatest poets, this is a moment of performance portraiture. So we think of our new auditorium in effect yet another gallery. Having just the right place to do it with the real theatrical capabilities is for us a great new attribute for the National Portrait Gallery. And, as a last, we have decided to increase the accessibility for the public to what before were 'behind the scenes' aspects of museums. There will be an open storage facility with thousands of works on view. There will also be a visible conservation laboratory where the work of conservation staff will be on public view.

One of the major differences between Australian and American museums is the considerable role and support of private donors in the USA. How have you managed the role of sponsorship and donation in relation to the re-building and how successful has your fundraising been?

Well, actually the National Portrait Gallery was one of those few museums in our country, federally constituted as it is, to have enjoyed through most of its first 25 years of its existence (from 1968) complete federal support. This allowed us not only to maintain a good staff but also to count on monies for our exhibitions. That was paradise. Now we have only enough money for our staffing and anytime we have an initiative, including an exhibition, certainly commissioning works, we have to find private money. Then there were the demands associated with the museum's building restoration, This involved a lot of effort but also the opportunity to raise monies for purposes we never dreamed possible. It actually represented the opportunity to get money we might not otherwise have attracted. In the end, the grandest connections and opportunities for fundraising happened around the establishment of initiatives that could be then attached to the name and interest of a particular donor. One example is our portrait competition. In Australia, of course, you have a venerable portrait competition tradition, the Archibald prize, but it is not associated principally, with the National Portrait Gallery of Canberra. We look more toward the model of the English National Portrait Gallery, which is I believe now in its 22nd year. Our goal, like theirs is to interest visual artists who might not have been drawn to portraiture. I discovered happily that one of our docents of 20 years standing was not only remarkable in her knowledge and affection for the Portrait Gallery, but also had considerable resources available to her. We are naming our portrait competition, which will be the principal opening exhibition, the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. That was an example again of a dilemma becoming an opportunity.

With an expected re-opening date of 4 July 2006 in forthcoming months you will no doubt be re-installing the works of art. A number of recently opened museums such as MoMA and the Tate Modern revealed a new way of looking at and displaying the collections. Will you similarly be trying new approaches to the hang?

I don't presume to think that our hang is so radical. But we will be changing what was a bit 'genteel' about our earlier display. There will be some variety in the typeface, and in some of the colours we might use, and also in strategies of placement. In the case of one American sculptor of the 20th century, I'm contemplating having the exhibition be mostly about how his subjects responded to each other and the artist. For example, famously, one of his subjects, Scripps, who was a newspaper mogul and very conservative rather snarled at the artist, Jo Davidson, because he had heard that a time before he had sculpted Mother Jones, who was one of the great radicals of the time, 'Who's paying for that?" he asked and Davidson said, 'You are!' because Davidson used the money that he made sculpting prosperous citizens to do projects that responded to his own progressive politics. Having Scripps 'confronting' Mother Jones, in placement, implying a sense of an actual conversation going on between them, is the kind of thing that we would do that would not require enormous new technology or machinery but would add a certain liveliness. Also, we have not titled our various galleries. We have instead chosen quotations that are almost like haiku. They give a feeling for that moment where those portraits and people gathered in that era.

You recently opened an Australian portrait exhibition at the Embassy of Australia in Washington DC. You commented that there were real differences between Australian and American contemporary portraiture. Could you please elaborate?

Your question gives me the opportunity to say something that I feel quite profoundly. Australia and America only seem to be similar, or at least are perceived by Americans, as similar. In fact they are very different societies with very different styles. And I think it is made apparent in certain ways through portraiture For example, many would argue that we are both bold societies but actually. I think Australian boldness, when it manifests itself, is really far stronger in spirit. And so there was, literally and figuratively, an 'in your face' aspect to the Australian portraits. They were larger and more direct. If you look just around my office as we speak, all the eyes in the portraits are averted. Why that is would take a lot longer than I have now to explain. But that was one very strong quality in the exhibition at your Embassy.