Sir Cecil Beaton, photographer, illustrator, theatre designer, artist, diarist and author, worked extraordinarily hard for more than forty years, but his art was such that his dedication was seldom detected.

In the late 1960s he referred ruefully to the popular view of him as a 'rather glib fop wearing startling Edwardian clothes and appearing as if my work came without any effort'. In fact, looking back, one of his friends judged it his genius to subsist by working constantly with superficiality without succumbing to it himself. Although photographic portraiture was just one aspect of his career, following his pioneering 1968 photography exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery London one critic judged him the equivalent in photography to Sir Joshua Reynolds in painting. Beaton, he said, 'grasped from the very beginning that portraiture is not so much about likeness as about imagery'.

Cecil Beaton was born into a middle class family in Hampstead in 1904. It was not long before his father, a timber agent, noticed that Cecil was 'becoming peculiar', poring over fashion plates and photographs of stage beauties. He was sent to school at Heath Mount in Hampstead, to be bullied by Evelyn Waugh, who later based a character on him in Decline and Fall. He finished school at Harrow, where, in a pair of boots he had ordered specially from a Harley Street specialist, he feigned disability to avoid sport and army drills. Over three years at Cambridge he filled 38 diaries, designed costumes, makeup and scenery for the Amateur Dramatic Company and performed with the Footlights. He left without taking his degree. While still at Harrow, Beaton determined to become a Royal Academy portrait painter. At the same time, he began taking photographs, encouraged by his younger sisters' nanny, who developed and printed her own films. After he came down in the summer of 1925, he threw himself into portraying his sisters Baba and Nancy, persuading the lovely creatures to dress in costume and pose upside down, under glass domes or amongst a litter of tulle, tinsel, flowers and silver raincoat material. Photography, interior decorating, and acting all attracted him as careers, but as his debts mounted he found that taking pictures was the most remunerative of these options. Accordingly, he became a 'professional photographer by accident'. A period of vigorous social climbing in which his photographs were occasionally published culminated in the first of many sessions with Edith Sitwell (it was 'well worth while nearly dying of a rush of blood to the head', she wrote). This marked the beginning of his photography career. Following the success of his first exhibition of photographs, drawings and stage designs in late 1927, he began drawing for the new London version of the American magazine Vogue. Under contract to Vogue on and off for the next two decades as photographer, illustrator and writer, Beaton was to make a greater impact on its reputation than any other artist.

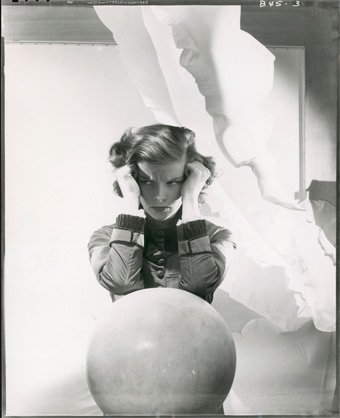

Beaton took the first of his many trips to America over four months in 1928-9, soon making influential friends and gaining opportunities for drawing, writing and portrait photography. On assignment for Vogue he photographed Hollywood stars including Fay Wray, Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, Buster Keaton and Gary Cooper, whom he found 'absolutely charming, very good looking... such a good sort that he made one feel such a swine.' Throughout the prewar years Beaton returned intermittently to the USA while continuing his program of penetrating every crevice of English high society. In Pans he consorted with Jean Cocteau, Bebe Berard and George Hoyningen Huene. Berard and Cocteau inspired him to paint backdrops for his photographs, and perhaps under Huene's influence, he began taking more fashion shots. No photojournalism Beaton explained his deliberate approach to photography: 'The camera is a mirror of actual facts. Hence if the photographer is also to be an artist he must pose his sitters and prepare his decorations so as to place before the camera in physical reality those inward facts of life with which an artist is concerned.' By 1930 Osbert Sitwell already knew that 'it is to his photographic portraits that the people of the next century will turn when they want to rediscover the character of this one.'

When Beaton first saw the King's mistress, Wallis Simpson, he judged her 'a brawny great cow', but by the time he photographed and sketched her in 1935 she had acquired the scrawny chic that his photographs preserved for posterity. All in all, Beaton did well out of the abdication. English and American Vogue ran portrait spreads of Wallis, and he took her wedding photographs with the Duke of Windsor. English Vogue ran his peeresses in the Coronation issue. Henceforth, from 1939 into the 1970s, he was the favoured Royal photographer. One of the dewy pictures from his first session with the Queen (the late Queen Mother) was reproduced on the sovereigns' Christmas card in 1939. Beaton commemorated the young Princesses' birthdays; the birth of Prince Charles, the Coronation; he even rose to the diplomatic challenge of Princess Margaret's wedding to rival photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones. Prince Philip was usually obstructive - 'If he's not got what he wants by now he's an even worse photographer than I think he is!', he once cried -but the young Queen liked his work as much as her mother did. Roy Strong has observed that Beaton contributed profoundly to the Yorks' public image. The Queen Mother wrote to him: 'I feel that, as a family, we must be deeply grateful to you for producing us, as really quite nice and real people!'

Just before the onset of war came an incident that was to dog Beaton on and off for most of his career. In one of his illustrations he used, as he put it, a slang word of which he did not appreciate the full implication. As a result, he was required to resign from Vogue on account of his supposed anti-Semitism. Disastrous loss of American-based income, reputation and opportunity ensued, and a new seriousness in him was discerned by his friends. Still, his first war-related activity was to mount a pantomime for English troops. 'I cannot think Hitler feels more unnerved and responsible than I now do', he said as preparations proceeded. Following a suggestion of the Queen's, he secured a job taking photographs for the Ministry of Information. On the basis of the enormous impact of his picture of tiny bomb victim Eileen Dunne, published on the cover of Life in September 1940, Vogue took him back. Over the early 1940s he worked in Egypt, India and China, quickly publishing successive books on the war effort in the East. In Cairo he met Dick Casey, then Minister of State, who asked him not to portray the English soldier as a 'speckled spotty little chap'. Casey later described him as a 'man of parts', and his wife Maie found him 'a person quite unlike my expectations, a serious man whose perceptions reached with compassion beyond skin or flesh'.

Involved with the performing arts for nearly all his professional life, Beaton designed costumes and sets for successive generations of ballet, theatre, film and opera stars. He dressed Margot Fonteyn, Tallulah Bankhead. Vivien Leigh, Katherine Hepburn and Barbra Streisand. He created versions of Verdi for the Met; Shakespeare for the Old Vic; Sheridan for the Comedie Francaise. He took an acting part in a San Francisco production of Lady Windermere's Fan that he designed. His interest in theatre encouraged Beaton to believe that he could write his own play. He worked on it for years before it premiered in Brighton in 1951. Just before it opened - to poor notices - he wrote 'I can't, after the excitement of the last few weeks, just go back to taking photographs'. He was still revising the script into the 1970s, but had had to go back to taking photographs long before that.

One day in 1932, when he had his snakeskin shorts on, Beaton met Greta Garbo, who had been infuriatingly elusive on his previous visit to Hollywood. A flame sprang up instantly between them. After charades and Bellinis they had an ambiguous sort of encounter in his room - 'if I were a young boy I would do such things to you', she murmured. They did not see each other again until after the war. The declared love of his life, Garbo was equal to marganne heir Peter Watson in Beaton's affections, but treated him worse, for longer. Some fourteen years after they first met, Beaton and Garbo went on a few dates. He photographed her, and planned to marry her. However, furious that his photographs of her were published in Vogue, she did not see him again for some time. Over the ensuing months he tried to play hard to get, but the game was gruelling. When she finally appeared at his room in New York's Plaza Hotel and drew the mustard velvet curtains he found himself 'hardly able to bridge the gulf so quickly and unexpectedly.' Though his potency 'baffle(d) and intrigueldl and even shock|ed) her', he would often affront her inadvertently with an innocuous gesture or action. When she came to stay with him for two months in 1951, he was thrilled, yet he confessed that she was 'a full time job and an anxiety as well as a pleasure'. Truman Capote wrote to Cecil that 'she will never be a satisfactory person, because she is so dissatisfied with herself, and dissatisfied people can never be emotionally serious.' In 1958 she came to London, where she rang from Claridges to say 'I thought we might try a little experiment this evening at 6.30". Whatever it was, Beaton was taken aback by it. That year he gave up on the dogmatic temptress and fell in love with a kind young widow, pressing her to marry him despite declaring 'a great queer streak which might make things very difficult'. She tactfully refused. In 1965, observing Greta during a cruise on Cecile de Rothschild's yacht, Beaton wrote that 'having loved her so much it is a nightmare for me to see to what inevitable paths her negativeness and selfishness have brought her' The end came ten years later, when Garbo came to see him at his home following his severe stroke in 1974. While he made to embrace her, crying 'Greta, the love of my life', she shrank away; she said to his secretary 'Well, I couldn't have married him, could I? Him being like this!' She signed the visitors' book and left his life.

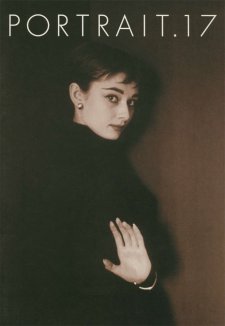

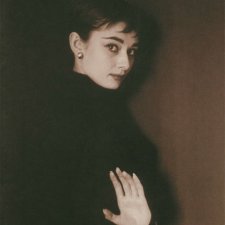

In 1955 Beaton began work on his greatest design triumph. My Fair Lady. The stage show, starring Julie Andrews, premiered in New Haven, Connecticut and soon police were holding back the crowds vying for seats. Beaton's heightened fame was his ticket to photograph Marilyn Monroe. 'She romps, she squeals with delight, she leaps onto the sofa... It is an artless, impromptu, high-spirited, infectiously gay performance. It will probably end in tears,' he wrote. Once My Fair Lady was running Beaton turned to creating the sets and costumes for the film Glgi. for which he won an Academy Award. In April 1958 My Fair Lady began its smash run of 2 281 performances at London's Drury Lane. Beaton spent ten months of 1963 living at the Hotel Bel Air in Hollywood, working on his sets and costumes for the film version. When Audrey Hepburn saw the results of Beaton's first photo session w:th her, she wrote: 'Ever since I can remember I have always so badly wanted to be beautiful. Looking at those photographs... I saw that, for a short time at least, I am, all because of you.' He won the 1964 Academy Award for costume design and art direction for My Fair Lady.

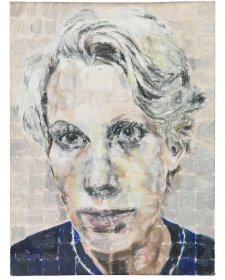

In 1953 Beaton had enrolled at the Slade School to study two days a week, intent on becoming a proper painter. An exhibition of his paintings, in which one critic saw the influence of both Francis Bacon and William Dobell, was held in London in 1966. It included a portrait of Mick Jagger, based on a photograph by David Bailey. Beaton and Jagger met up in Marrakech, and they continued to see each other around London as Beaton earned the nickname 'Rip van With-lf through his appeal to the young set. After a sellout exhibition of his paintings in Palm Beach, California, in 1968 Beaton flew on to Australia, to stay at Admiralty House with his wartime colleague Dick Casey, now Governor-General. He encountered a few old friends including mauve-haired Robert Helpmann, 'more viperish than ever'. He visited Canberra and Melbourne, and returned to Sydney to stay at James Fairfax's home on Darling Point. He summed up the trip: 'This is certainly a country of great future, but at the present time it is still extremely jejune and there is nothing that appeals to me... it made no lasting impression.' On his return to England he photographed Maie Casey's friend Patrick White, whom he had photographed many years before. According to David Marr, White felt the pictures made him look like a stuffed sea-lion.

The first of Beaton's two crowning triumphs was a pioneering exhibition of his photographs at the National Portrait Gallery London in 1968, curated by its radical young Director, Roy Strong. Beaton Portraits. 1928-1968 - the first exhibition of photography at the National Portrait Gallery, the first time living sitters had been exhibited, and the first time non-British faces had been displayed - was a huge popular and cntical success. The second of his great London exhibitions was in 1971, when an outstanding selection of historical and contemporary fashion selected and collected by Beaton was staged at the Victoria and Albert Museum. He was knighted in 1972. Some two years later, he suffered a major stroke. However, he learned to draw and write with his left hand, to speak and walk, and was back photographing Bianca Jagger in a see-through Emanuel dress in 1978 At the end of that year he was invited to take photographs for a special Beaton issue of Paris Vogue. It came out in March 1979 with classic shots of all the prettiest girls in Paris. A few weeks short of a year later, he died quietly at his English country home, having survived his cat by a week.

The information in this article is drawn from Hugo Vickers's scintillating authorised biography, Cecil Beaton (1985).