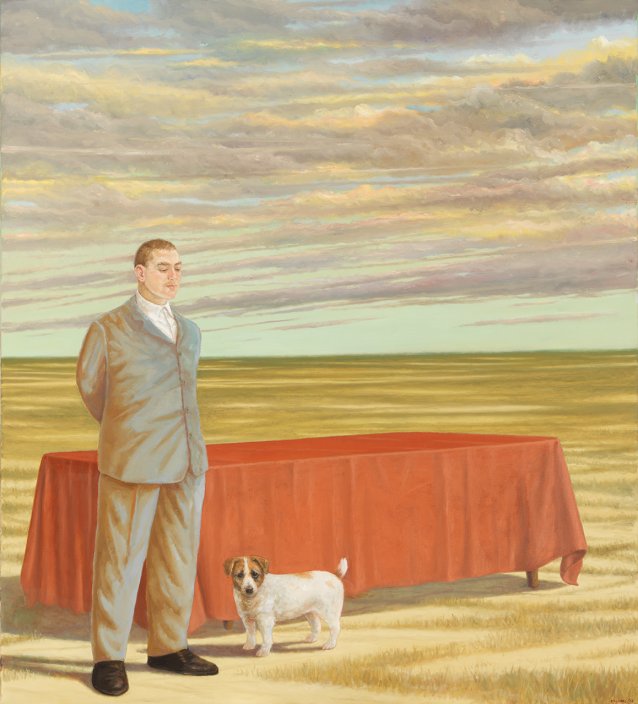

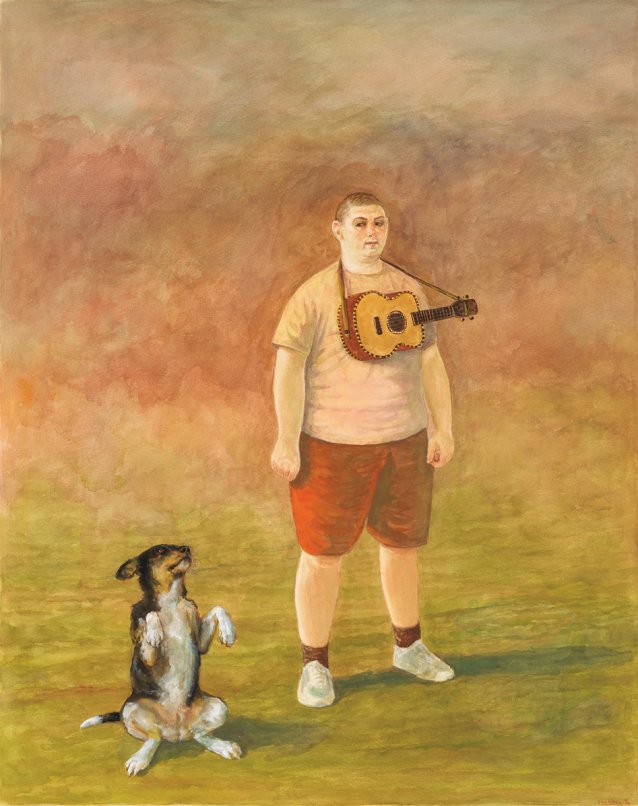

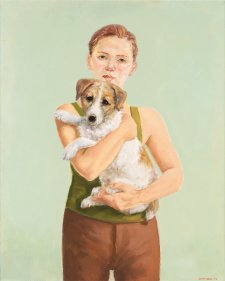

On canvas, the brown-and-white dog’s seen her share of outlandish events over the years. She’s snoozed belly-up with office workers dancing round her in a conga line. She’s dozed beside wrestlers competing for male kewpies. She’s posed with a group of three chaps, one in a green and lilac skeleton costume teamed with brown moccasins, one in big yellow trunks and one in a Superman outfit. She’s licked the face of a man in purple at a party under the stars, not far from another man in a Fair Isle jumper and a skirt made of peapods. She’s never fazed.

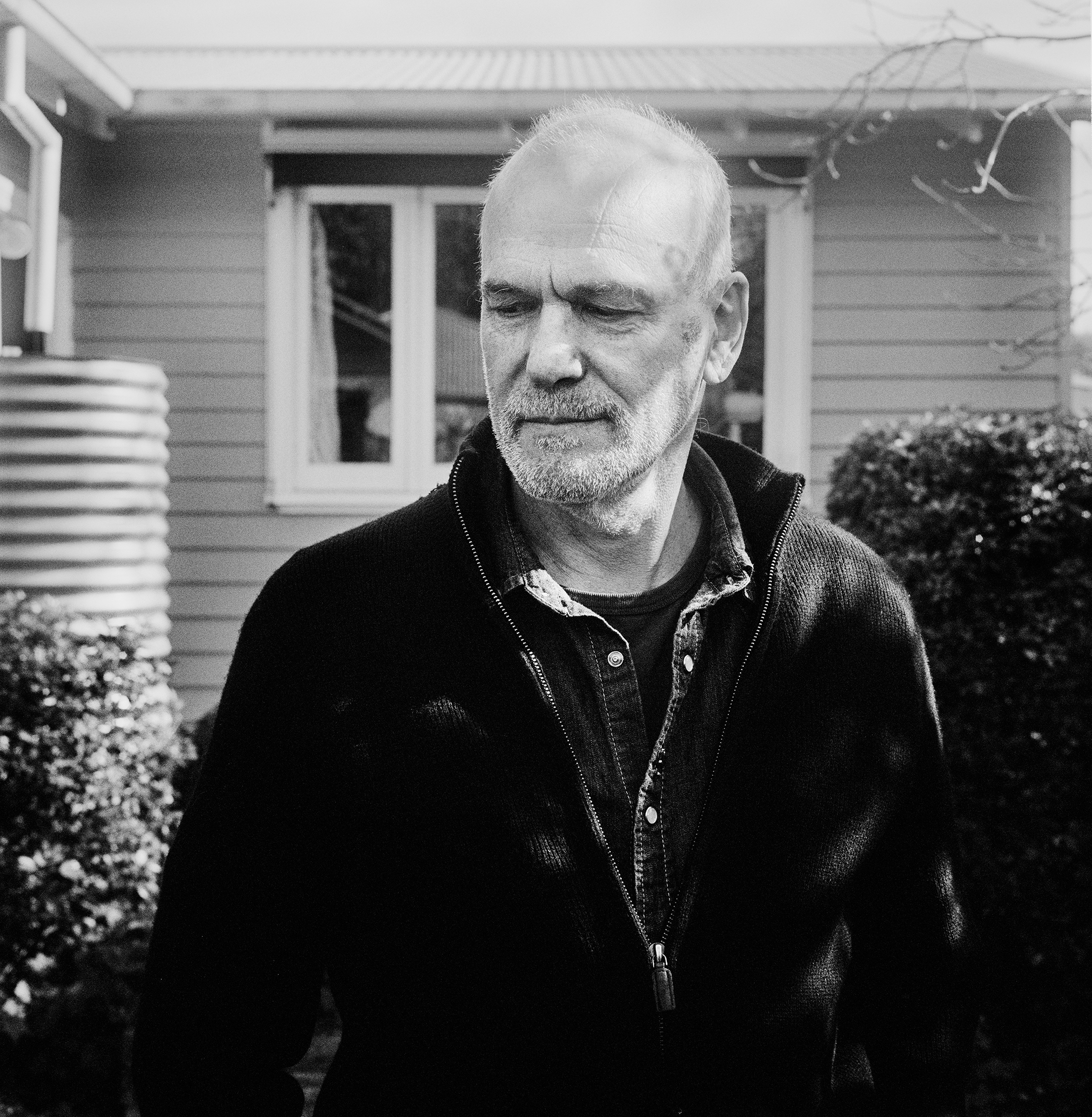

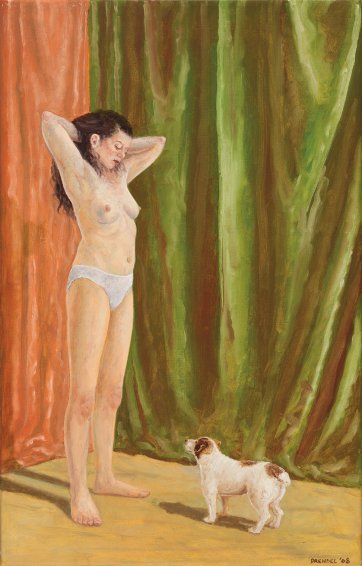

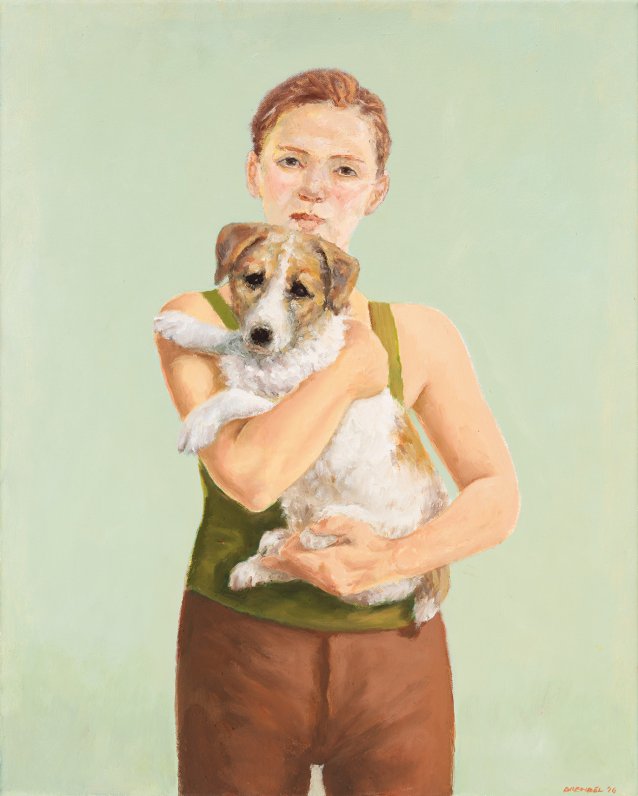

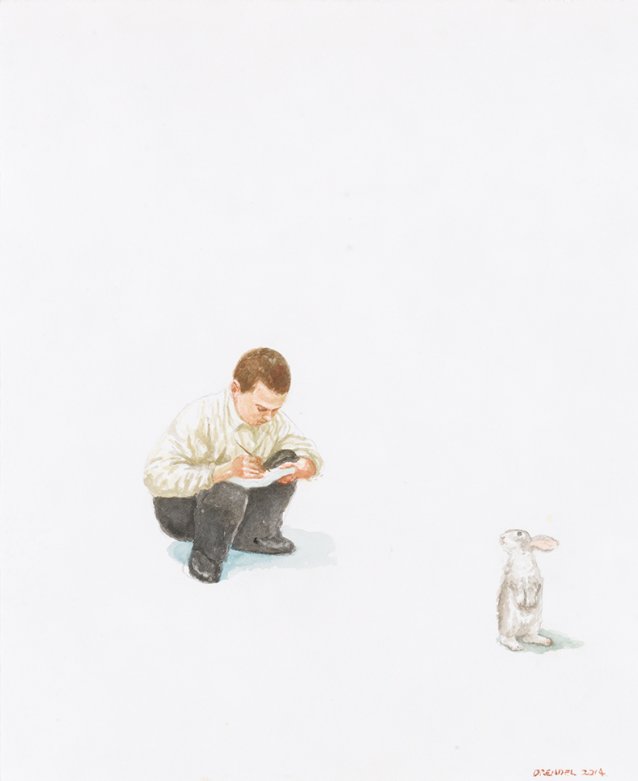

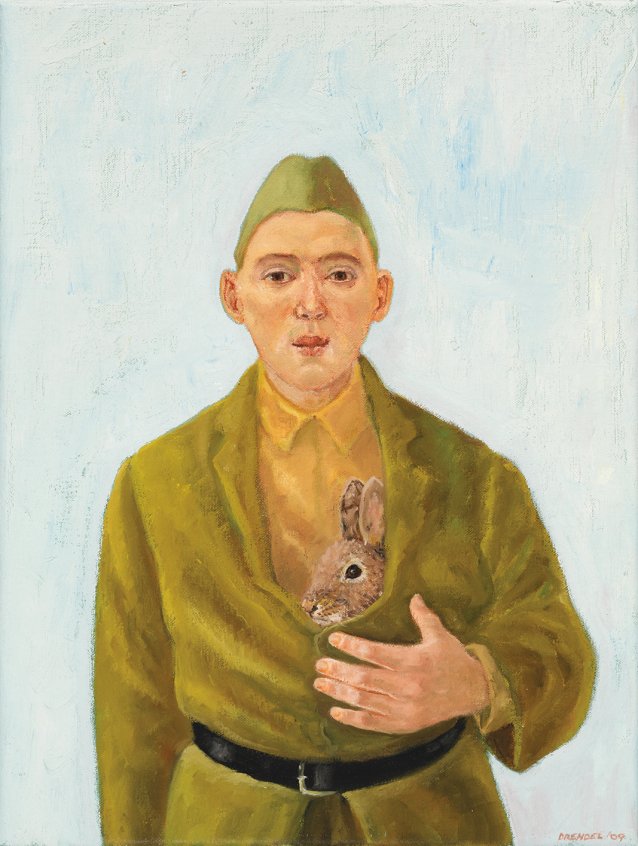

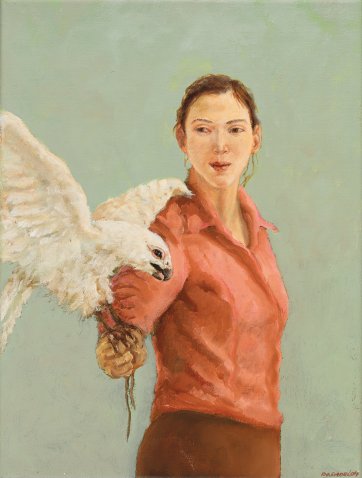

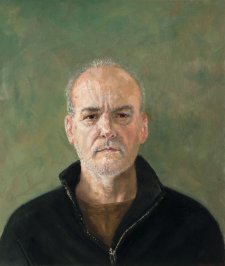

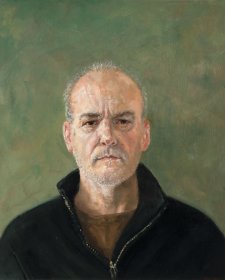

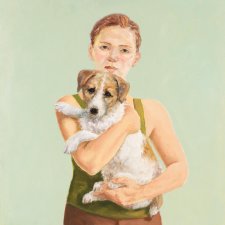

There is nothing zany about Graeme Drendel himself. He’s a handsome down-to-earth husband and father who spent his childhood on a farm in the Mallee in Victoria, then moved to Melbourne to qualify as an art and craft teacher. For decades, now, he’s been working in the same studio, behind his yellow weatherboard house at the end of a quiet street of Coburg in Melbourne. It’s stacked with paintings he’s made over the years, hung from floor to ceiling with works he’s getting ready for sale, crowded with easels, piled with books, full of wooden filing cabinets, shelves and old plan drawers crammed with sketchbooks. The warm brick step of the studio isn’t far from the laundry door; every day, he takes the twenty-nine paces from house to studio feeling apprehensive. Graeme’s equally attractive partner, Wendy, grows the flowers and vegetables in their cottage garden, sprinkled with unusual plants like the blood lilies his mother gave her. As well as spending a lot of time improving her soil, Wendy’s the artist’s muse and adviser, plus his accountant, and often poses for the figures in his paintings; he says she both is, and isn’t, all of the females, and a lot of the males. They have a small dog: a furry, shaggy little terrier called Pippie; for many years, she was basketmates with a lookalike animal, Lucy. Pippie looks like the dog in the paintings, but that’s their late dog, Billie. She was smoother, so nicer to paint.